Healthy humans have trillions of bacteria that live on and in our bodies. They help break down foods and teach our immune system how to behave.

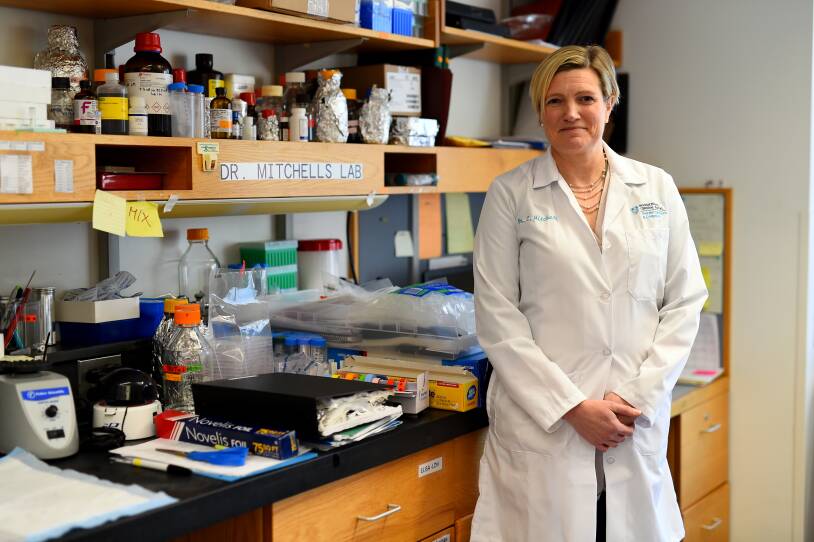

“In just about every site in the body, diversity of your bacterial community is great because it serves lots of functions. But the vagina is the only place where simplicity is the goal,” said Caroline Mitchell , an obstetrician gynecologist and researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Ideally, a vagina is dominated by just one type of bacteria. However, about a third of women nationwide have a lot of different types of vaginal bacteria, which is associated with a sometimes-devastating condition called Bacterial Vaginosis.

For the first time in the United States, a medical team led by Mitchell and her colleague, Douglas Kwon, will begin performing vaginal microbiota transplants this month.

While their study is focused on treating patients with Bacterial Vaginosis (BV), the results of the transplant study could have implications for a long list of ills, from HIV transmission to preterm births.

The Vagina's Superhero

The human vagina is unlike the vagina of any other creature in the animal kingdom.

What a healthy human vagina unique is that it's dominated by one type of bacteria — lactobacillus — and one species seems to be best of all. That special species, Lactobacillus Crispatus, is sometimes called "the superhero in the vagina."

This isn’t the lactobacilli you find in tiny print on dairy product labels or the lactobacilli that scientists find in our gut. "They're totally a different set of species," Mitchell said.

When a woman does not have a lactobacillus-dominant environment, she develops BV.

“The way it's described in many clinical texts is discharge and odor, which sounds really minor if you’ve not had it yourself,” Mitchell said. But in her clinic, Mitchell said, many of her patients report that these symptoms can completely disrupt their life.

"Many people say: 'It's ruined my relationship. I feel like I'm not a sexual person anymore. I'm embarrassed,'" said Mitchell. "They're miserable. They're uncomfortable."

In addition to the symptoms, Mitchell said BV is associated with while a whole host of health risks. Women with BV are at twice the normal risk for preterm births and miscarriages, and at a two- to four-times higher risk of contracting HIV if exposed. It’s also associated with other sexually transmitted diseases, including human papillomavirus, gonorrhea and chlamydia. And, Mitchell said, there may even be a link to infertility.

Scientists are still figuring out exactly how this all works. They think that good bacteria, lactobacillus, create a more acidic environment that is protective of the tissue and reduces inflammation. And that inflammation, for example, seems to be the link between BV and preterm birth.

While nearly a third of American women have this condition, Mitchell said a majority of those women do not have any symptoms. But with or without symptoms, they have the health risks.

Doctors do not know why some women get recurrent BV or how to fix it. Right now, the standard medical response is a course of antibiotics.

"At one month after treatment, about 60 percent of people are cured, which is terrible," Mitchell said.

Considering how many women are affected, Mitchell said she thinks that the treatment should be far more effective. Mitchell acknowledged that part of the reason why there isn’t currently a better solution — and hasn’t been a definitively new treatment in decades — is because people find vaginal discharge "gross" and women’s sexuality and sexual health is "not valued or prioritized."

However, she also said, this area is hard to study.

Because there is not any other creature with a lactobacillus-dominant vagina, researchers can’t test treatments in mice, monkeys or some other animal. “We are unique,” Mitchell said. “That's interesting and fascinating, but it makes the research very challenging.”

It means researchers have limited options: Try out something new in a petri dish in a lab, or test it in people. Mitchell and Kwon’s team is making the leap.

Vaginal Microbiota Transplants

In a randomized controlled trial, their plan is to transplant vaginal fluids from healthy women and put them in women who keep getting BV.

They have spent months screening donors to make sure they have a very stable, healthy vaginal microbiome, testing people to make sure they don’t have infections and then collecting donations — basically fluid gathered by using a disposable menstrual cup.

The key to the transplants is the lactobacilli, but it’s not just the lactobacilli.

Mitchell and her team are hoping that if these transplants are successful, they will show what mixture of things are needed for a healthy ecosystem in the vagina. It could be a combination of bacteria, fungi, metabolites, mucus, nutrients, sugars and other things found in the fluid.

"It's very different than just transplanting bacteria — using a probiotic, for example. It's the entire ecology from one woman that's transplanted to another," said Jacques Ravel, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, who is not involved in this transplant study but is eagerly awaiting the results.

Other researchers — including at the University of California, San Francisco — are trying the approach of seeing if a vaginal probiotic, with the good bacteria but without the accompanying ecosystem, can do the trick. Those results are not yet available.

"If this [transplant] approach is actually working, we can learn a lot about what kind of ecology is more efficacious than another," Ravel said. "I see this as a major first step."

However, Ravel said these transplants are difficult to do for several reasons. There is a risk of infection, limited material available in each donation for testing, and the bacteria — even in healthy women — can vary from day to day based on things like diet and stress levels.

Thus, the goal is not to eventually roll out vaginal microbiota transplants to the general population. Instead, Ravel and Mitchell said, these transplants are best done in the context of studies where all the donors and recipients can be thoroughly tested and monitored.

"I think, ultimately, we can try to reproduce that ecology in vitro — in the lab — and make capsules that are a lot safer,” said Ravel.

Mitchell said she agrees. If all goes well, she said she'd like to see a new treatment available to the public in five to 10 years. The hope, she said, is for the third of women who have BV to have a treatment that could actually cure the condition — and also reduce preterm birth and HIV transmission rates.