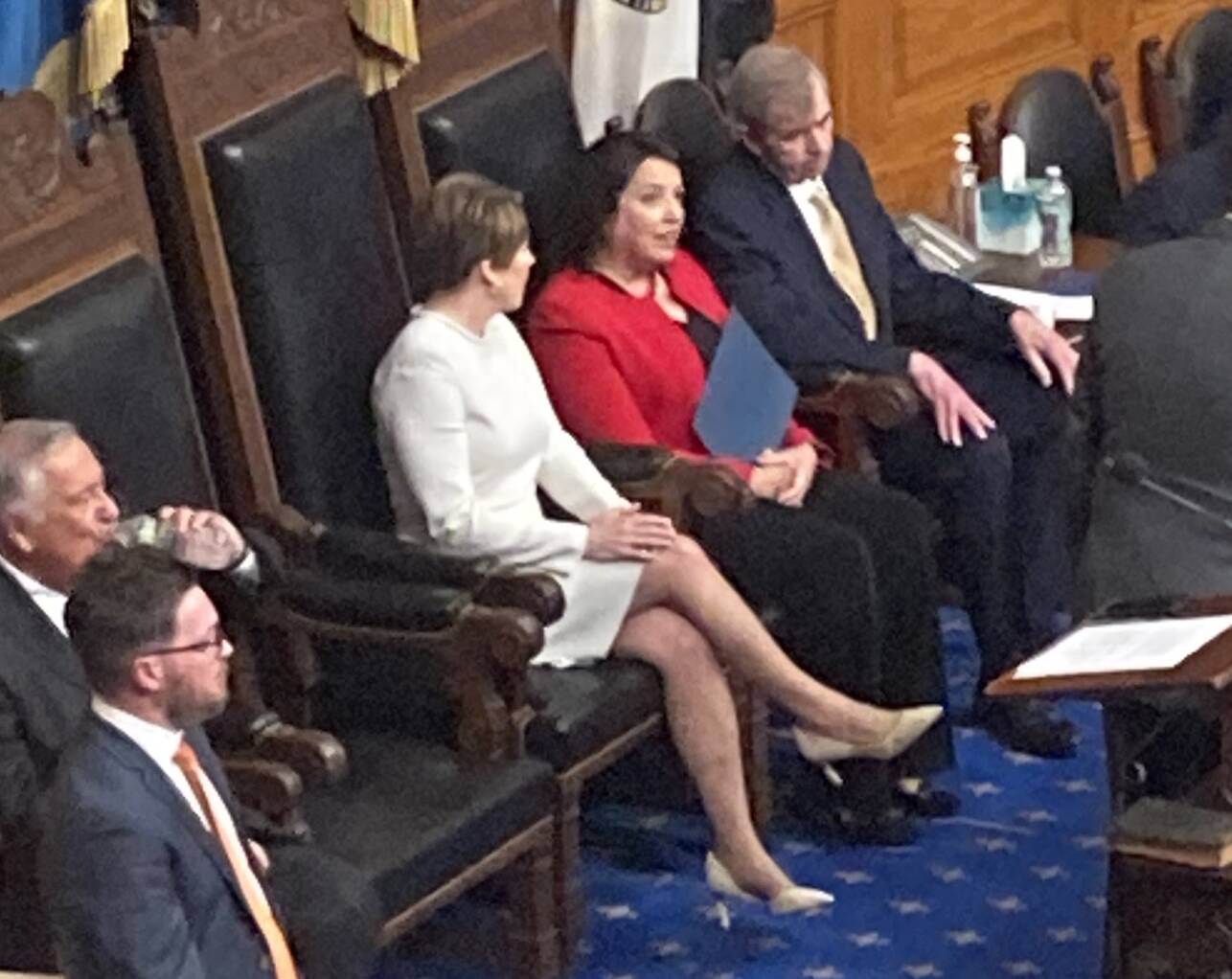

Two years ago, in the Massachusetts State House, Gov. Maura Healey sat in a large wooden chair in the center of the House Chamber on the day of her inauguration.

You may not have noticed, but her feet didn’t reach the ground.

The chair is too tall for the 5-foot-4 governor, who took it over from 6-foot-6 former Gov. Charlie Baker. She still sits in that seat for events like State of the Commonwealth.

“They don’t make furniture for women, right? ... My feet still don’t touch the ground, so maybe that’s something I can work on,” Healey said with a laugh.

It’s not just about furniture that’s not built for women, but an entire system. Women in Massachusetts politics and beyond know the phrase well: “The old boys’ club.”

However, the tide is changing.

“I remember when I was being sworn in and looking around this huge House chamber ... and realizing that, you know, this was going to be a big responsibility I was walking into,” Healey recalled.

In just the last few years, the Bay State has locked in historic firsts, including voting in Healey as its first elected female governor, and Michelle Wu becoming Boston’s first elected female mayor.

Wu said the historic nature of her inauguration hit her when her young son Cass asked if boys could ever be mayor of Boston.

“It was such a part of his understanding that he sees Mom — other women, girls — in positions of power making decisions,” Wu said.

The rising power of women in Massachusetts politics isn’t just confined to statewide office or big cities, though. It’s happening in the smallest towns in all corners of the commonwealth, according to a GBH News examination of the data.

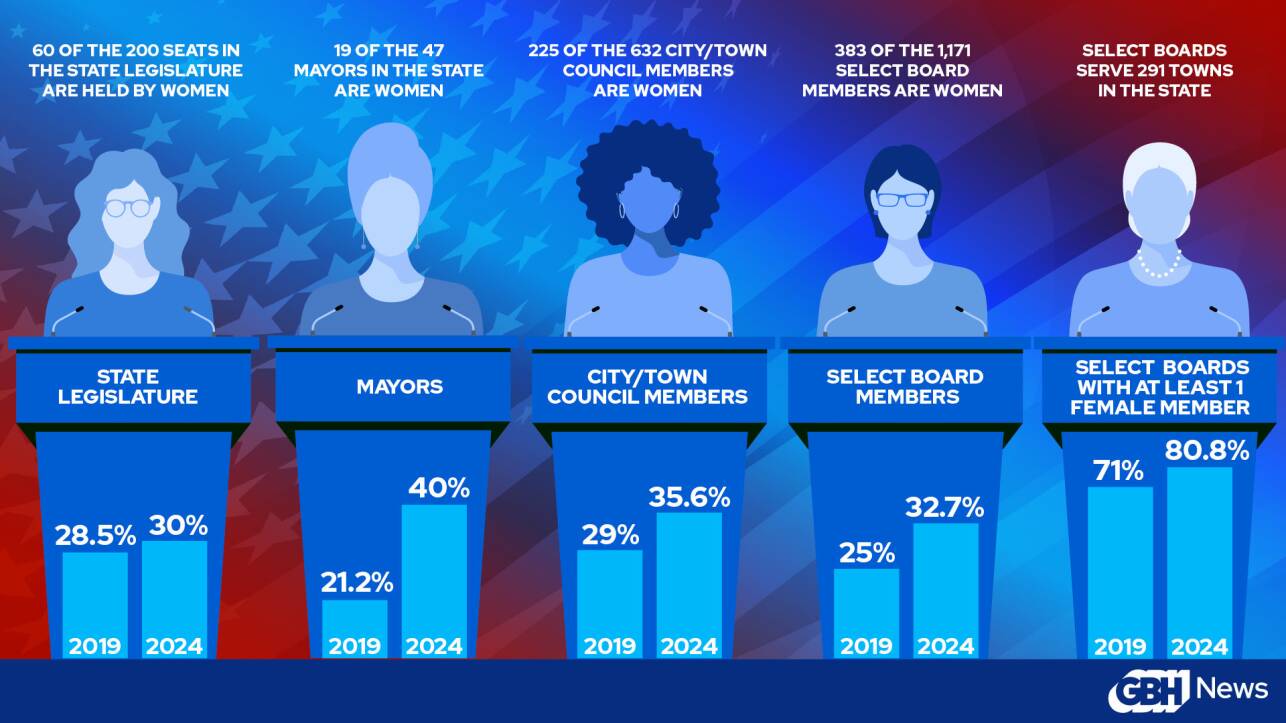

In 2019, GBH News embarked on a data project to quantify Massachusetts’ “original old boys’ club.” Five years later, that club appears to be breaking up, at least on paper.

At the time, Massachusetts had just 10 female mayors. That number has now nearly doubled, to 19 out of 47 total across the state.

Newton Mayor Ruthanne Fuller is one of them. She was elected as the city’s first female mayor in 2018, and is now in her second term.

“As a woman leader, perhaps a little bit different from men, I am happy to say ‘I’m sorry.’ ‘I don’t know.’ ‘I need your help.’ Those statements feel good and useful and authentic to me. It’s a little bit of stereotyping, but men, I think, generally don’t lean in that way,” Fuller said.

Compared to Fuller, Melrose Mayor Jennifer Grigoraitis is new to the job. Speaking with GBH News just six months after her January 2024 inauguration she said, “There can be a belief that we have to be perfect in order to put ourselves out there. … You don’t need to have every single box ticked and every part of your life lined up in order to do this.”

Kassandra Gove of Amesbury became the city’s first female mayor in 2020, beating a six-year incumbent, and she’s been reelected twice since then.

Gove, who is also the city’s youngest-ever mayor — age 34 when she took office — is on track to become the city’s longest-serving mayor. She’s Amesbury’s fifth mayor since the town became a city in the late 1990s.

“One of the things that was really important to me in coming to office was to make the office of the mayor really approachable, to sort of take it down a level to show people that they could do this, too — to be that role model that they haven’t had in this office,” Gove said.

By the numbers

Of the 1,171 select board members across the state, nearly 33% are female, compared with 25% just five years ago. Those numbers are similar across city and town councils, which are made up of nearly 36% female members compared to 29% five years ago.

Fifty-six select boards have no female members at all, down from 85 boards, while only one town — Egremont — has an all-female board. There are no all-male city or town councils.

Since the early 2000s, the percentage of women serving as lawmakers on Beacon Hill had hovered around 25%. In 2018, that number ticked up slightly to 28.5%. Following the recent 2024 state primary, it will be up to 30%, which is not expected to change significantly come November due to a limited number of contested races statewide.

According to the Center for American Women in Politics at Rutgers University, Massachusetts ranks 19th in the country for its percentage of women elected to municipal office — at 33.2%. (The state at the top of the list, Colorado, has a near 50-50 split.)

What does it mean?

Women are 360-degree leaders who bring their full lived experience to the job, according to Amanda Hunter, executive director of the Barbara Lee Family Foundation, a Cambridge-based organization that has researched women in politics and helped get hundreds into office across the country. Now, decades after activist Barbara Lee founded the organization, it will sunset in December.

Hunter said the Massachusetts boys’ club is over. “We think we are not going back, and I think that’s a national trend as well.”

Laurie Nsiah-Jefferson, director for the Center for Women in Politics and Public Policy at UMass Boston, said having women in office allows younger generations to picture themselves doing the same.

Healey said she notices the reaction of young girls, “They see me elected. It means something to them … and I appreciate that.”

Nsiah-Jefferson described female leaders as more likely to tackle the everyday struggles affecting voters, like child care, housing and health care.

Having women on select boards has a trickle-down effect, she added, as those boards often hire administrative staff and make appointments to other town committees.

“Historically, when white men have been making those appointments, they tend to perpetuate their network, which tends to be white and male,” Nsiah-Jefferson said.

Fuller echoed that sentiment, saying that you can literally look under the table to see evidence of how women in power have shifted whose voices are heard.

“When you go to a meeting, look under the table and peek at people’s shoes,” she said. “If you see all sorts of different shoes at the table, you’re much more likely to make better decisions because you’re bringing different ideas literally to the table.”

Healey said that representation is essential.

“When women haven’t been in the room, this is why we have ended up historically with laws that don’t provide coverage for contraception and insurance plans,” she said.

Women in politics still face challenges

Despite immense strides in female leadership in the last several years, the commonwealth still has work to do.

“When I walk into a room, the first thing people notice is that I’m female,” Fuller said, adding that it’s still true in her second term.

Other elected officials shared similar experiences.

“The very first meeting that I walked into, it was clear that some of the members thought I was a staffer. They didn’t realize that I was the new mayor of Melrose,” Grigoraitis said.

For Gove, it’s not just about gender. She gets more comments about her age, but she is also questioned about her wardrobe, her relationship status, and whether or not she has children.

“It’s not a system that’s built for us,” Gove said.

Several elected officials interviewed noted that women need to provide more evidence of their accomplishments than men when running for office, and many women hold the idea that they need to be “perfect” to run.

Gove noted that often female candidates center their accomplishments over personal information, evidenced by male candidate online profiles.

“The description is like ‘proud dad, husband, and dog lover’ or whatever. But if you look at a female candidate’s page, it’s all of her credentials, how many degrees she has,” Gove said. “We have to sell it that way. It’s not going to be a picture of her with her kids. It’s just not.”

Hunter added, “What we find is that men can simply release their resumé, and it’s taken for granted if they say that they held a job. That’s usually enough information. We say that men can tell, and women have to show.”

Melinda Barrett, the first female mayor of Haverhill, said in retrospect, she wishes she had run earlier.

“Women always want to be perfect and be the expert, I think that’s our tendency. I think we want to have all the degrees. … There are guys out there faking it to make it — and you can do the same,” Barrett said.

A historic era

While women continue their rise in Massachusetts, they’re also looking nationally to the dead heat race between Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump.

“You’d like to think that if there’s ever been a time where we’re ready, that it’s now, right when women’s rights have been completely under fire,” Gove said.

Though she’s expected to pick up an easy win in Massachusetts, the latest polls show Harris and Trump virtually deadlocked in most battleground states.

Healey said of a potential Harris presidency, “She would be the first woman elected. And it’s about time. I mean, it is important. It is significant. And, you know, it’s just unfortunately been this ceiling, this barrier that, you know, unfortunately has taken us until 2024 to see through it.”

Looking toward the future in the Bay State, Nsiah-Jefferson expects there will be more women in office in Massachusetts.

“We have a critical mass of leadership in Massachusetts,” she said. ”I think that that mass will facilitate and encourage other women to move forward.”

Their advice: Don’t wait

For other women thinking about running for office, current elected officials resoundingly said one thing: just do it.

“You can’t win if you don’t run,” said Barrett.

Healey advised having a tough skin and a good sense of self, “Don’t let people talk you out of it. Don’t. If you’re a woman, don’t let people say it’s not your time.”

Wu said in addition to thinking about what you have to offer, also consider what the community would miss out on if you didn’t run.

“What voices wouldn’t be represented if you’re not there bringing the entire community with you into decision-making?”

The data for this story is based on information gathered from the Massachusetts Municipal Association, town and city websites, and hundreds of confirmation phone calls made to officials in municipalities across the state. Some information may have changed since data was collected in spring/summer 2024.

GBH News interns Olivia Ray, Valentina Baez and Layla Chaaraoui contributed to this story.