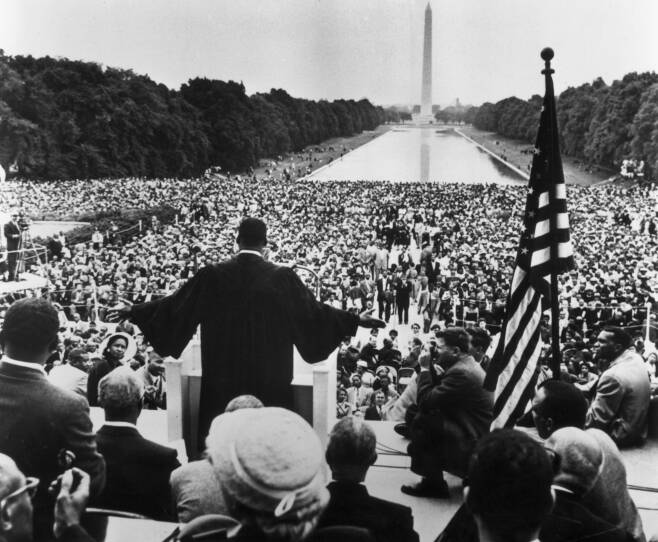

On May 17, 1957, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stood atop the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and addressed a crowd of 25,000 that massed to demonstrate in the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom . “Give us the ballot,” he declaimed, “and we will no longer have to worry the federal government about our basic rights.” It was an early event of the civil rights movement, and decades later, his solemn exhortations resound in the voices of his descendants.

Ahead of Martin Luther King Day, the King family is requesting that celebrations for the observance of his birthday be deferred until the legislative and executive branches of the U.S. government can make headway on securing voting rights in the 21st century. Specifically, that means passing the John Lewis Voting Rights Act , which effectively restores the provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965; and the Freedom to Vote Act , which aims to safeguard elections from “voter suppression, partisan sabotage, gerrymandering, and dark money.”

“You delivered for bridges, now deliver for voting rights,” said Martin Luther King III , putting the political will to pass the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act next to the standstill bedeviling the voting reform bills.

Local leaders recalled the power and awe they feel at the ballot box — knowing, particularly, the fight that forged their road to voting. Despite disenchantment with democracy and ever-persistent divisions, they described a firm hold on hope in interviews with GBH News to look back on King’s legacy.

In 1983, despite personal opposition, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill recognizing Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a federal holiday. But “holiday” connotes jubilation and celebration of what is and was, not recognition of the progress that still must come. “In this country, there are holidays of celebration, and I don't believe that the King Commemorative Day really ought to be thought of as a holiday,” said Ted Landsmark, a professor of public policy at Northeastern University and director of the school’s Kitigan Michael Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy. “[It should be] thought of as a day of public service and of commemoration of a life that is dedicated to human rights.”

For Landsmark, this “holiday” is no day for rest; it’s best observed with work — work that contributes to the realization of King’s vision for a more just society and the democratization of the franchise.

Millions of votes are cast nationwide on election days, and the sheer volume of ballots can make it easy to forget just how central the act of voting is to the American identity. If it weren’t, then the Founding Fathers and framers of the Constitution wouldn’t have restricted the franchise to wealthy-enough white men. If it weren’t, Congress wouldn’t have had to pass an entire amendment to nominally give that right to Black men. Black and white women wouldn’t have had to fight for suffrage, and the darker races of the continent would not have been routinely tortured and murdered for trying to exercise that most fundamental constitutional right. Crosses wouldn’t be burned and bridges wouldn’t be crossed. The collective vote is the most powerful; if it weren’t, then why so many efforts then and now to repress it?

These were the issues that loomed large for Landsmark when he cast his first ballot. He was involved in the fight for voting rights long before he stepped in the booth. As a youth, he had participated in fundraising for the Freedom Rides of 1961 and done background work for the March on Selma. When he was finally able to vote himself, he remembers the experience being particularly moving because “I understood that people had died recently in the civil rights movement on behalf of protecting and enlarging the voting rights of African-Americans.”

Tanisha Sullivan, president of the NAACP’s Boston branch, fondly remembers her 2018 vote to send Ayanna Pressley to Congress. “As a Black woman? Just knowing how important a role we have played in shaping the political landscape across this country for so many generations, and to know her and to really experience the fight, the fortitude, the will, the determination that she had — not just for herself to become a Congresswoman, but to really do the work for the people,” she said. “Both ballots — I had the opportunity to cast one for Barack Obama, the other for Ayanna Pressley — they are not only memorable, they inspire me even today.”

Sullivan’s feeling, that her ballot had some heft, that it carried consequence, that it could even be carried at all was a clear goal of the civil rights movement’s mid-century era, and no one served as a more lasting figurehead of that movement than Dr. Martin Luther King.

Despite the historical weight the vote holds and the efforts of the King family to see through the passage of several bills, disillusionment has set in with large swaths of younger Americans. A majority of millennial voters — 55% — according to a 2021 report from the Centre for the Future of Democracy at the University of Cambridge. Civic disaffection is not just found in the United States, it’s endemic in many purported democracies and republics, including those in the United Kingdom, Australia, Brazil and Mexico.

"When we don't give up hope on our democracy, that's one of the greatest lessons of the civil rights movement. It's not giving up hope in the face of despair."Tanisha Sullivan, president of the NAACP’s Boston branch

But if you were to ask Imari Paris Jeffries, executive director of the nonprofit King Boston , this is hardly surprising. “I think it's up to our generation and other generations to understand that this disillusionment with democracy didn't occur in a vacuum,” he said. “There are real economic inequalities that exist, that prevent younger generations from achieving the quote-unquote American dream.”

The root of those inequalities, at least in Jeffries’ view, is the crippling atrophy of the system that makes things go. The public sphere is the birthright of democracy, he says, and the deterioration of that sphere — and its constituent parts — is undeniable. For example, he points to the idea that private school is more desirable than public school; that public transit isn’t worth it when private options are available; that even the achievement of getting into elected office has lost some of its privileged shine. “When the things that belong to all of us have deteriorated we can see why people and younger generations are not excited about, democracy ”

The American Federation of Teachers maintains that civics education in the classroom is in crisis, and Sullivan would identify that as a cause for the current democratic malaise. “We don't currently have a culture that fosters and celebrates civic engagement,” she says. “I think part of what we need to do is engage young people, from very early ages in government, helping them understand how powerful it is to to be a part of that process and how empowering it can be to just step into public service.”

She empathizes with the disillusioned, reiterating that she knows well the feeling that comes when you “look at our government and feel a sense of bewilderment and confusion and wonder if [your] voice matters.” But no one said this work was easy, and she still encourages them to stay true to the goals of the civil rights movement. “What I have seen happen from a historical standpoint, quite frankly, when we don't give up hope on our democracy, that's one of the greatest lessons of the civil rights movement. It's not giving up hope in the face of despair. It's not giving up a belief in what's possible, even when it seems like everything is chaotic.”