She’s ahead when it comes to polling and fundraising, but Attorney General Maura Healey has one big reason to be nervous as she runs for governor. Put simply, when Massachusetts AGs try to make the jump to the corner office, they don’t succeed.

Consider:

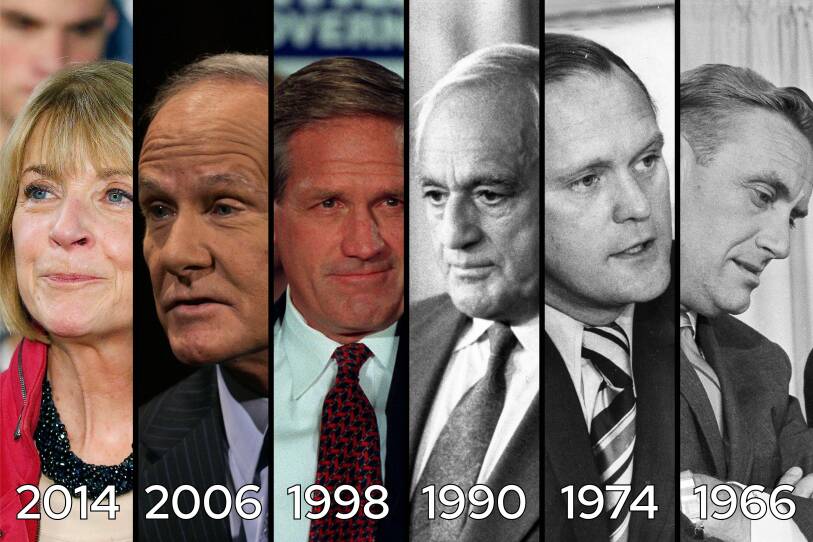

- In 2014, Martha Coakley lost in the final to Charlie Baker.

- In 2006, Tom Reilly finished third in the Democratic primary, which was won by Deval Patrick.

- In 1998, Scott Harshbarger lost in the final to Paul Cellucci.

- In 1990, former attorney general Frank Bellotti lost in the Democratic primary to John Silber.

- In 1974, Bob Quinn lost in the Democratic primary to Mike Dukakis.

- In 1966, former attorney general Edward McCormack lost in the final to John Volpe.

“But wait!” some local politics junkie is almost certainly objecting. “What about Paul Dever?” It’s true: Dever, a Democrat who won the governor’s seat in 1948, had previously served as attorney general. But he did so in the late 1930s — then lost in the 1940 governor’s race and served in the Navy in World War II before ultimately clinching the state’s top office.

In other words, Dever’s win comes with an asterisk.Sitting AGs haven’t been able to win races for governor at all — leading many Massachusetts political observers to speculate, only half in jest, about a “Curse of the Attorney General.”

The challenge now, for Healey, is figuring out what threads tie those losses together so she can avoid adding to the tally herself later this year.

One commonality jumps out right away. Like Healey, every single one of the failed AG candidates was a Democrat, a fact that points to one of Massachusetts’ defining political tics. Voters pick Democrats for almost every elected job in the state — but when they’re choosing governors, they tend to elect Republicans who can serve as real or perceived counterweights to the same Democratic dominance they’ve helped perpetuate.

But Jim Aloisi, who was an assistant AG under Bellotti and later served as Patrick’s secretary of transportation, also sees two more subtle patterns at play. When AGs actually win the nomination, he argues, they fare pretty well. But AGs have stumbled in competitive primaries when politlcal uncertainty dominates, and when they’ve been the de facto Democratic standard bearer and faced challengers who run as insurgents.

After advancing from the primary, Harshbarger lost narrowly, 51 percent to 47 percent, to a skilled campaigner who was the de facto incumbent after a year as acting governor. And in 2014, Coakley came even closer to victory in her showdown with Baker, losing by just 40,000 votes out of nearly 2.2 million cast.

In primaries, Reilly finished third behind Patrick, who enthralled progressives. Silber beat Bellotti by running from the right, as a proto-Trumpian figure who scorned political correctness. And even though Dukakis subsequently became a Massachusetts political legend, Quinn was the preferred choice of the Democratic establishment in 1974, when the country was mired in recession, the aftermath of Watergate and the war in Vietnam.

In other words, AGs have been at their political worst during moments like the one the nation is living through right now — and when facing rivals like Sonia Chang-Díaz, who’s already working to cast Healey as a status-quo candidate of limited vision. In February, for example, she chided Healey for backing changes to the state’s wiretapping law, tweeting that Healey and others “have repeatedly proposed legislation to expand police surveillance, while failing to seriously consult racial justice leaders & advocates. This is not what inclusive or equitable leadership looks like.”

“If you’re Maura Healey, and you’re looking at those patterns, you definitely don’t want to be outflanked by an insurgent in a primary,” Aloisi said. “You’ve got to think about how to avoid that. To not respect history, and assume that somehow this year will be different, is courting danger.”

But working for years as the state’s top lawyer can make political maneuvering difficult. Consider a recent appearance on GBH’s Boston Public Radio, in which Healey explained that she blocked Brookline’s push to ban new construction heated by fossil fuels not because she thinks it’s a bad idea, but because state law says municipalities can’t pass their own building codes. “When you have a situation where a bylaw conflicts with state law,” Healey said, “it can’t go forward.”

It exemplified a dynamic that Harshbarger, the ex-AG who lost to Cellucci in 1998, recalls experiencing in his own campaign for governor. He says people sometimes assume that decisions made by AGs, driven by careful legal consideration, reflect personal preferences or animus instead.

“[The public] may think you’re being fair, but the people you sue always remember you sued them, or challenged them, or raised issues,” Harshbarger said. “There were people who said, ‘You sued my company, and you want me to hold a fundraiser? Forget that.’”

"To not respect history, and assume that somehow this year will be different, is courting danger."Jim Aloisi

That friction can extend to the political realm. In 1998, Harshbarger recalls, some of his fellow Democrats balked at his pursuit of political corruption cases involving their friends and colleagues. And not everyone appreciated his campaign-trail insistence that the Big Dig — the $24 billion federal project that remade Boston transportation — was neither on time nor on budget.

“I was not seen as a party loyalist,” Harshbarger said.

In retrospect, Harshbarger says, that perception may have helped him as much with voters as it hurt. Still, more than two decades on, his frustration is palpable as he recalls then-House Speaker Tom Finneran linking him to the “Looney Left,” and big-name Dems like Finneran and then-Boston Mayor Tom Menino effectively sitting out the race.

It's hard to imagine the same thing happening in this election cycle. While the Democratic establishment distrusted Harshbarger, Healey has come to embody it. What's more, Cellucci, Harshbarger’s opponent, was a moderate Republican with whom many elected Democrats were already comfortable collaborating. In contrast, if Healey is the nominee, there’s a good chance she’ll face Geoff Diehl, who’s been endorsed by former President Donald Trump and has embraced the Mass GOP’s Trumpist turn. That's a political threat elected Democrats are unlikely to take lightly.

Lately, too, the most reliable constant in Massachusetts politics has been change. Barriers that once seemed insurmountable have been shattered in recent years — whether it’s Patrick becoming the first Black governor, Coakley becoming the first female AG, Elizabeth Warren becoming the first female U.S. Senator, Healey becoming the first openly gay AG in the state and nation, Ayanna Pressley becoming the first Black female congresswoman to represent Massachusetts or Michelle Wu becoming the first woman and person of color elected mayor of Boston.

For Healey, the best-case scenario is being seen not as the latest in a long line of AGs who tried and failed to reach corner office, but as her own woman and candidate. When she kicked off her campaign in January, and was asked how she differs from her failed predecessors, Healey shrugged off the question.

“I’ll leave that to others,” she replied. “I’m probably the shortest that’s ever run. And I will tell you that I have great respect for those who’ve served as attorney general.”

That may prove to be an effective approach. Andrea Cabral, who worked for Harshbarger before becoming Suffolk County Sheriff and later served as Patrick’s public safety secretary, hasn’t endorsed in the Democratic primary. But she promises that, when she votes this September, the idea that an AG can’t win won’t factor into her decision at all.

“I think if you have the right person who’s running for governor, who’s in the office at the right time — and this may very well be one of those times — that that person can get elected,” said Cabral, who is also a GBH News contributor. “It’ll be a total non-issue for me.”

For now, at least, many Democrats seem to agree. But unless and until Healey actually gives a victory speech in November, the idea of an AG’s curse is likely to linger. In the meantime, if Healey hits a rough patch, expect it to enjoy a renaissance. The history that idea represents and the disappointment it evokes for Democrats are just too potent to forget.