In the early 20th century, American women won the right to vote. Soon, women’s participation in the workforce, education and political life all increased dramatically.

This gender revolution took place not just in the U.S., but in many countries throughout the world.

But beginning in 1980, the changes in opportunities, status and attitudes that were closing the gap between men and women began to slow. Since the mid-1990s, there’s been little change.

Gender equality at home among heterosexual couples has progressed even more slowly than in public life. The family theorist Frances Goldscheider has argued that the goal of moving women into what has traditionally been men’s territory in the paid labor force is just the “first half” of what she calls the gender revolution.

Without progress on the “second half” of that revolution – men picking up an equal share of work at home – other efforts, such as equal pay, won’t be enough to make the work that women and men do equitable.

My colleagues and I at the World Family Map project collaborated with Goldscheider to understand whether having children made the goal of fairly dividing work at home more elusive.

We found, consistent with previous research, that having children at home made men and women behave more traditionally. Women cleaned, cooked and cared for the children far more then the men did.

But we also found lots of variation across countries in how much children “traditionalized” couples’ division of labor. We wanted to know why the presence of children mattered more for how couples divided work in some countries – like Finland and Lithuania – than in others – like Norway and Latvia.

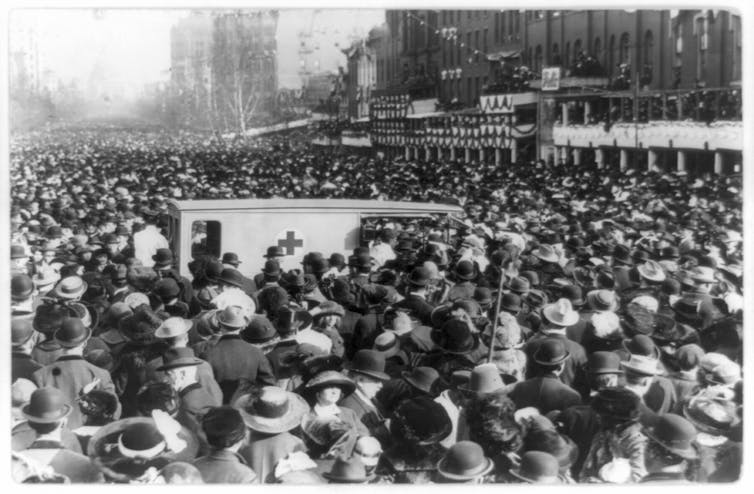

How much have women’s rights progressed in the U.S. since the women’s suffrage movement? Library of Congress

Surprising answers

We looked at how men and women divided their time between paid work, childcare and housework using the most recent International Social Survey Programme’s data on family and changing gender roles.

The data covers 35 countries representing northern countries as well as relatively wealthy countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean.

We looked at several factors that we believed might explain why couples divided up household work the way they do, including national income, national family policy and national gender equality.

We used the Global Gender Gap Index, which measures equality in health, education, the labor force and political representation, to measure gaps between men and women in public life.

When we began our analysis we thought that children would be less of a factor in how labor was divided at home in countries with more gender equality in the public sphere.

We were wrong.

In 76% of Northern European childless couples, the women put in equal or more paid hours than the man did and he put in equal or more domestic hours than she did. In other words, 3 out of 4 couples were not gender traditional in their division of labor.

But only 45% of Northern European couples with children practiced a non-traditional division of labor.

In comparison, 31% of childless couples in Central and South America divide labor more equally. But having a child doesn’t change the status quo by much. Just 21% of couples in this region with children divide labor more equally.

Where both partners typically work outside of the home, children typically contribute to a “second shift” much more for women than for men. This means that children present a greater obstacle to a gender revolution in its later stages than one that is just getting underway.

A solution?

The most surprising finding in our analysis was that the loss of momentum toward gender equality differed among countries. We wondered if government policies could be an influence.

Generous parental leave that could be used by either parent didn’t seem to affect things – the workload still broke down into traditional roles if there were children.

Legislation providing fathers with legal protection if they took unpaid parental leave didn’t move the needle, either.

We tested many other policies that didn’t seem effective.

Only one specific family policy stood out: non-transferable paid paternal leave – also known as a “father’s quota.”

When use-it-or-lose-it paid leave was offered, men participated more at home.

Among couples with children across our 35 countries, 28% practiced a modern division of labor without the father’s quota, and 34% with it. This difference is significant, and its magnitude is almost exactly the same as the change associated with an individual moving to a higher level of education.

Fathers’ quotas emerged in Norway in 1993. Sweden soon followed suit. By 2012, fathers’ quotas were also found in Belgium, France, Portugal, Latvia and Japan.

Forcing changes in cultural norms

Our data doesn’t tell us why the paternal policies seem to help close the gender gap.

If fathers’ quotas were created by policymakers in response to progressive values – if they simply reflected gender norms rather than changing them – we would expect to see those values reflected in a couples’ division of labor whether or not children were in the household.

But the policy does not impact gender equality in domestic labor among the childless in those countries. About half of childless couples practiced a modern division of labor regardless of whether there was a father’s quota – 49% without, 51% with.

And we can’t prove how a father’s quota influences behavior.

But we know that forces that push men and women into “non-traditional” roles may have lasting results if the rewards of the new behaviors are self-reinforcing. One example: When men enjoy nurturing their children and therefore want to do more of it.

This worked during World War I, when seeing women plow fields, deliver mail, enforce laws, drive buses and assemble munitions countered the stereotypes of women as too fragile or disinterested in non-domestic work.

If the gender revolution is stalled or stalling because men are seen as ill suited for domestic work, a paid benefit that makes their paternity leave more of a cultural norm may be the force that changes society’s perceptions and behavior.

Laurie DeRose, Adjunct Professor, Georgetown University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.