Fifty years ago this week, the country watched on television as Neil Armstrong walked on the moon. Broadcasting those images live was no small feat — one that wouldn’t have been achieved without an often overlooked device made in Massachusetts.

The 1969 moon landing of Apollo 11 was a major TV event. When Armstrong opened the door of the lunar module — called the Eagle — the Westinghouse slow-scan camera attached to the door was rolling in black and white. The live moon show began. Hundreds of millions watched as Armstrong made his way to the moon's surface, probably as awestruck as Walter Cronkite, the CBS News anchor.

“There he is. There’s a foot coming down the steps. So there’s a foot on the moon. Stepping down on the moon,” Cronkite exclaimed. “Boy! Look at those pictures. Wow!”

To get those pictures transmitted through outer space back to Earth, the video signal needed a boost, which came from a little device developed at Raytheon in Waltham. It’s called the QKS-1300 Amplitron.

As retired Raytheon engineer Bob Zagrodnick puts it, the Amplitron had one very important job: “To boost the power of the signal that you want transmitted, to boost it to the level powerful enough to go from the moon to Earth without too much loss through the atmosphere and then be received by the antennas on the ground stations.”

At the time, Zagrodnick was the lead engineer for the Apollo test group at Raytheon. Nestled in the lunar module’s communication box was this unassuming, softball shaped device. Inside the Amplitron were crossed-field microwave tubes that amplified the TV signals of the footage taken on the moon. Without the device, no one on Earth would ever have seen or heard Armstrong’s famous quote: “It’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

Several deep space tracking stations were in place on Earth for the moon landing, but the one in Canberra, Australia, received the signal first because it was facing the side of the moon where the Eagle had landed. From there, the signal bounced to mission control in Houston, where it was reformatted for TV sets. The resulting picture was grainy, but no less extraordinary.

“Neil Armstrong is on the moon. Neil Armstrong, 38-year-old American, standing on the surface of the moon.” Cronkite said, in awe.

It was already a high stakes mission. But in addition to flying a shuttle through 240,000 miles of space, entering lunar orbit and landing safely on the moon, Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin also served as the live TV crew, while fellow astronaut Michael Collins manned the command and service module.

Read more: The Natick Army Lab That Helped Feed The Men Who Went To The Moon

Inside NASA, the idea of televising the moon walk had been fraught with controversy. Jennifer Levasseur, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, said the agency’s public relations department wanted to capture every moment of the Apollo mission, but the astronauts’ managers saw the TV as a distraction.

“The television coverage throughout the entire early space program is always controversial amongst the astronauts and the managers, because it's seen as the least valuable in terms of their goals,” Levasseur said. “If they could have just avoided the television entirely, a lot of them probably would have.”

But Congress was writing the checks, with money from taxpayers. At the time, TV was not only the ultimate public relations tool, it was also a way to show the Soviets that the U.S. had accomplished President Kennedy’s ambitious plan to send the first man to the moon before the end of the 1960s.

In the months leading up to the Apollo 11 lunar landing, Zagrodnick and his team in Waltham had to make sure the Amplitron worked. While his primary focus was making sure all the parts of the Apollo Guidance Computer were in working order, he was also in charge of testing the broadcast microwave device.

“We tested all of the equipment that went on all the command modules, all the lunar modules, and we had to certify that they were reliable and good to go before they left the facility,” Zagrodnick said.

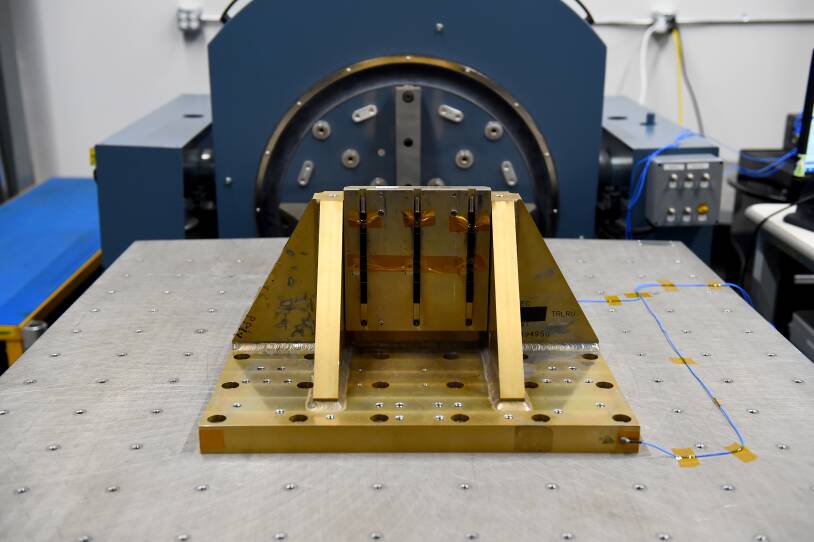

One way of making sure any hardware was able to withstand space flight was to use a vibration chamber that mimicked the acceleration, speed and turbulence of a launched rocket. A 21st century version of that chamber sits inside the Environmental Test Lab of Raytheon’s Andover facility. It’s called an electrodynamic shaker, also known as the “shaker table.” It's metal and about 5 feet by 5 feet with a mount on top. It faces a large amplifier.

“Each rocket has its own specific profile. The one we’re going to run today is a generic one that envelopes all rockets," said Joe LeBlanc, the lab's principal mechanical engineer. “This is the shaker amplifier, so this is what drives the electrodynamic shaker. And then we bring up what they call the gain, and we’re ready to run.”

Everyone in room was then instructed to wear earplugs. At first it sounded like he turned on a dishwasher, but quickly the table started shaking back and forth and the sound transformed into something like the chirping of crickets. When the shaker table finally reached its peak ultrasonic vibration, it did sound like a rocket about to break the sound barrier.

That is how, then and now, to make sure something can withstand being launched into space.

The Amplitron is now considered a relic and sits on display in a lobby on Raytheon’s Andover campus. But the same kind microwave technology it used is everywhere. High power, crossed-field amplifiers are used in radar and satellite communications and broadcast radio signals.

There’s another surprising legacy that the televised moon walk brought us: cable TV news.

All three networks that existed at the time — CBS, ABC and NBC — had poured millions of dollars into producing simulations and dramatizations of what was happening in space and on the lunar craft and aired hours of live continuing coverage. At the time, the 30-plus hours of continuing TV news coverage was unprecedented.

“By having so much sustained coverage, they actually established a paradigm for 24-hour cable news,” said Deborah Jaramillo, associate professor of film and television studies at Boston University. “So what people saw was a nascent formula for cable news with experts, right? Walter Cronkite had a retired astronaut by his side explaining things. So we had experts, we had analysis, filmed interstitial content, animation, simulations — all of these things.”

Like so many people who made the Apollo mission possible, Zagrodnick downplays his role.

“I lived it. I lived through it,” he said, laughing.

When asked if he’s ever thought about the fact that he was part of television history, he demurred.

“No, I never have, actually. I never really thought of it that way,” he said.

But Zagrodnick agrees that if we hadn’t witnessed the moon walk, it wouldn’t have been that monumental.

“That’s absolutely right. That fact brought home to everybody [what] the program was about, just to be able to see it,” he said.

Thanks, in no small part, to a little device called the Amplitron.