A half century ago, black student protests rocked campuses across the country from Boston University to Northwestern University, from Cornell University to Washington University in St. Louis.

African-American enrollment at top colleges had begun to grow, albeit slowly. The black students who got in organized to demand more black students, more black professors and courses in African-American studies.

Some activists took over campus buildings, while others orchestrated sit-ins. But at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island the protest unfolded differently.

On December 5, 1968, three-quarters of the African-American students at Brown walked off campus, with female students leading the way. That moment set the stage for changes that are still felt in the Ivy League today.

“A stifling, frustrating, degrading place”

When Ido Jamar from Washington, D.C., arrived on the Providence campus in 1965, she was one of just a handful of black females in her class.

“I had a lot of white friends – or I thought white friends,” recalled Jamar. “Parent weekend came, and not one of those white friends acknowledged me when they’re with their parents. And I said, 'Okay.' And so that was the beginning of looking at things differently.”

It didn’t take long for Jamar, who studied applied math and particularly enjoyed computer science, to realize that many of her fellow African-American students also felt like the university hadn’t created a sufficiently comfortable or welcoming environment for them.

Sheryl Brissett Chapman, who was a few years behind Jamar, said, “It felt like we were still being seen as descendants of slavery.”

Brissett Chapman, then Sheryl Grooms, had grown up in a strong African American community in Boston. She said that upbringing made her expect respect.

“In Roxbury, I was validated,” she said. “I was seen as an asset.”

But as a college student, that hadn’t been her experience.

Randall Ward, a Brown student from Chicago in the mid-to-late 1960s, said he dealt with the situation by leaving campus often. He became deeply involved in tutoring the African American children on the East Side of Providence.

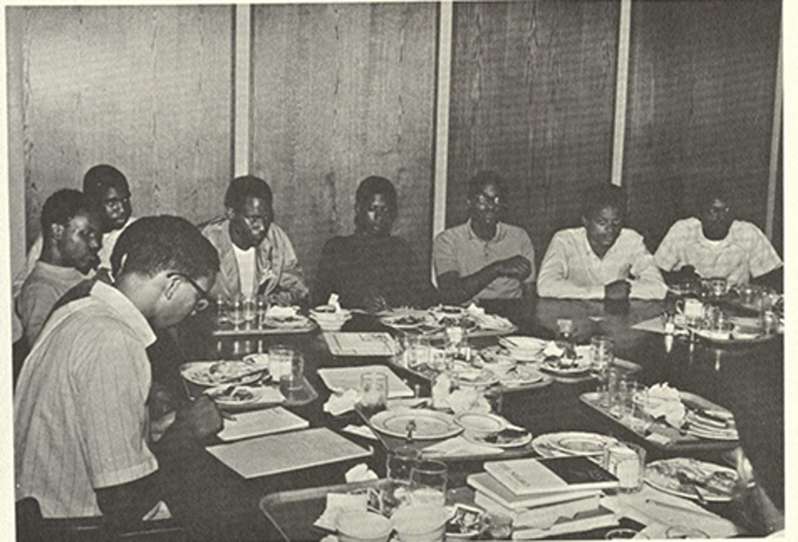

Before long, the students formed the Afro-American Society – or the AAS – in 1967 and started lobbying Brown and Pembroke, the affiliated women’s college, to make changes.

They wrote letters, met with administrators and gathered data. The AAS collected numbers on the schools’ admission rates: 2-3 percent of students identified as black.

AAS members set out to prove to the admissions officers– through numbers and through their own recruitment efforts – that there were plenty of qualified students of color. The university just wasn’t looking in the right places, the student activists said.

In May 1968, AAS members formalized their concerns in a three-page letter to Ray Heffner, Brown University’s president. “The University has been laboring under the mistaken impression that we are happy here because we have been quiet," they wrote. "We cannot afford to be quiet any longer. Brown is a stifling, frustrating, degrading place for black students. This situation is especially intolerable in a university which professes to be a bulwark of American liberalism.”

The AAS outlined 12 demands. They sought an increase in the number of African-American staff members, professors and admissions officers. They wanted a scholarship fund for black students, a place for them to gather, a major in African American studies.

Most of all, they asked that the student body to be at least 11 percent African American to reflect the country’s population at the time.

Heffner said he was staunchly opposed to establishing any sort of quota system, the Brown Daily Herald, the student newspaper, reported. He did offer to try to admit 35 black women the following year, which would work out to a bit more than 11 percent at Pembroke.

The two sides went back and forth with the AAS insisting the 11 percent was not a quota but a minimum guideline. Still, the university administration resisting anything that might resemble a quota.

By Jamar’s senior year, she felt the university was too slow to change and too resistant to the 11 percent goal.

“It became clear that just asking wasn't going to be enough,” she said.

“We’re only visible when we’re not there”

Jamar, whose name was Judith Fitzhugh when she was a student, recalled meeting with others and debating how to demonstrate their seriousness to the university.

“This was a time,” Jamar said, “when you had to choose between non-violence and violence.” The civil rights movement was in full-swing. Martin Luther King Jr. had just been assassinated.

It was also a time, she said, when “things were getting infiltrated.” She remembered that there were people who started showing up at AAS meetings nobody recognized.

“One person was clearly an outsider,” she recalled. “He came suggesting that he would provide guns for us.”

Ken McDaniel, a fellow student from Norfolk, Virginia, and member of AAS, recalled being “offered support by a certain group willing to do physical damage to the university in support of us.”

The students at Brown and Pembroke refused all suggestions they commit violent acts.

“We wanted something that, we felt, everyone could take part of — that would keep us with the upper hand,” Jamar remembered. “Once you do something that someone gauges as illegal, you then lose power.”

She and the other women concluded they would disassociate themselves from the school. They would walk off campus.

Brissett Chapman said the logic was simple. “We’re only visible when we’re not there," she said. "We took a position that we were walking out, and we said to the men, 'You guys can walk out or not, but we’re walking out.'”

Gary Harris, who was from Linden, New Jersey, was a freshman at the time. He remembered writing to his parents — who hadn’t gone to college — and worrying about jeopardizing the goals for him and the sacrifices they had made.

“I was a repository of a lot of their objectives and a lot of their wishes,” he said.

Harris also weighed the risk of being kicked out of school.

“The Vietnam war is going on and there was the draft,” he said. “We were all here on student deferments and, if you were no longer student, you could be drafted.”

In the end, Harris joined the walkout. All told, 65 of the 85 black students walked out Dec. 5, 1968.

The day played out in dramatic fashion. There was a last-ditch effort in the middle of the night to avoid a walkout, a silent procession away from campus and a gathering outside University Hall of some 800 supporters.

At 2:30 in the morning, before the walkout, Brown tried to avert the protest. The provost and associate provost were dispatched to meet with the black students and present a proposal. But the students rejected the offer, saying it did not address all of their demands.

Just before noon, the women and men gathered separately and marched to meet each other outside Faunce House on campus. From there, they walked the quarter mile down College Hill to a local black church, Congdon Street Baptist Church, which had agreed to open its doors to them.

“It was chilly,” remembered Glenn Dixon from Washington, D.C., who was president of the AAS during the walkout. “As we left campus, we left two by two.”

“We took pillows and books,” Brissett Chapman said, because everyone intended to keep up their course work.

It was “very sober, very quiet,” recalled McDaniel.

“When we got down to the church then discussion started," Harris remembered. "What we should do, how we should do it, when we should do it. There was a lot of talk into the wee hours. A lot of talk.”

When they finally went to bed, some slept better than others. Ward recalled waking up to find he was snoring so loudly other students had dragged him and his cot to the hallway.

“It was tense but respectful”

During the walkout, the students organized themselves with each person having a different job.

“My role was really talking to the white students and getting them to understand what we were doing,” Brissett Chapman said.

She tried to make it okay to talk about race, and talk they did. Some were critical of the walkout. An editorial in the Brown Daily Herald called the AAS’s actions "childish attention-seeking gestures."

Others were supportive. The New York Times reported that roughly 800 white students rallied for the cause. A black visiting professor at the time, Charles Nichols, spoke to them. “Are we going to make this a representative community, a representative university, leading in the effort to make this a humane society?” he asked.

While Brissett Chapman orchestrated and facilitated conversations on campus with white students, Ken McDaniel spoke to the media.

“Everything that was to be mentioned to the press — and answer to any question — was to be pre-discussed,” remembered McDaniel.

He also remembered the risk he felt he was taking as the public face of the activism. He worried that if word got back to his hometown, his father could lose his job.

The walkout at Brown attracted national media attention. But McDaniel said the students consciously did not link their efforts to national movements. “We were talking about Brown and what it said it was and wanted to be,” he said.

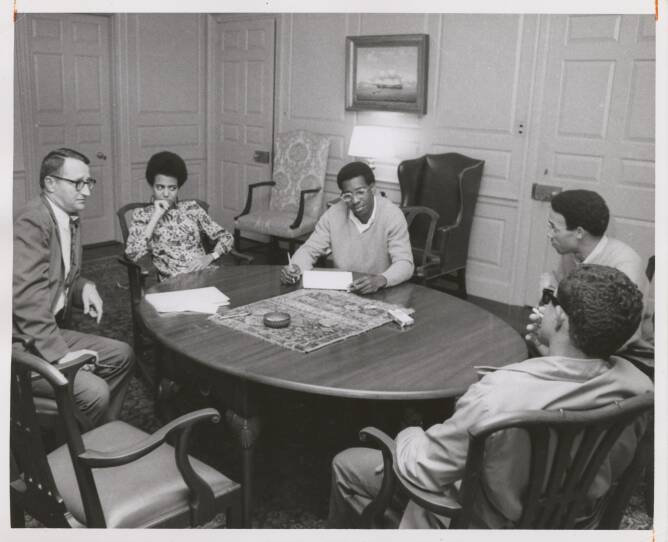

Gathering behind closed doors, Dixon was part of the negotiating team. He remembered the meetings with administrators as “tense but respectful. It was very business-like.”

It took several days before the students had secured commitments they felt comfortable with and agreed to return to campus. Brown promised to increase black enrollment and to devote a total of $1.2 million over the next three years to recruitment efforts.

Dixon knew the changes wouldn’t be immediate. “The achievement of the commitments was only evidenced by the students who came, the courses that were created, the faculty that were hired,” he said. “And those things took time to see.”

But Heffner, Brown’s president, told a local TV station, WPRI, that one thing didn’t take time.

As the walkout was ending, he said, he had noticed that “the faculty members, the entire Brown student community, the president looked in upon themselves and reexamined their philosophy and principles.”

“A more inclusive, welcoming place”

In the years that followed the walkout, real change occurred on campus.

The next entering class saw a surge in black student enrollment: 128 black students matriculated that fall of 1969.

Sandra Patterson Harris was one of those students. Coming to Brown from Girls’ Latin School in Boston, she said, she found “a welcoming environment because there were people around us.” She and the other black students quickly learned about the walkout and, Patterson Harris said, its participants were revered. “They were like gods,” she said.

That same year, a transitional summer program was created for entering students, an Afro-American studies program was approved, the Afro-American Society got meeting space and Brown’s governing corporation got its first black member, J. Saunders Redding, an early Brown graduate, historian and author.

Plus, the walkout became part of university lore.

Earlier this year, the Brown’s current president, Christina Paxson, mentioned the black student walkout in her convocation speech. “This moment set in motion five decades of work by faculty, staff and students to make this university a more inclusive, welcoming place for all,” she said.

“It really is a big part of black student life at Brown,” said Allison Harris, a member of the class of 2002. As a student, she learned her father had participated in the walkout.

Both Harris and her sister — Ashley Harris, who graduated in 2009 — said many of the programs created in the wake of the walkout were critical to their happiness as students. They met some of their closest friends in the transitional summer program. Ashley Harris spent much of her time involved in a black theater founded just two years after the walkout.

The walkout laid the foundation for other change.

“I guess it was my sophomore year that we saw that they were considering a black woman to be president,” Allison Harris said. “We thought it was the April Fools issue of the Brown Daily Herald. We just couldn’t believe it was true.”

It was true. In 2001, Ruth Simmons became the first woman of color to lead an Ivy League school. More recently, the university launched a Diversity and Inclusion Action Plan to further increase the diversity on campus.

But, Allison Harris pointed out that, when she was a student, there remained “a bit of anger or disappointment at the university.”

Through the years, students organized protests to demand that Brown recommit to the demands of the walkout — as has happened at other campuses across that country where black students protested in 1968.

Brown still has not met the core walkout demand that the student body reflect the general population. This year, the entering class is 9.3 percent black. Meanwhile, the nation’s black population has increased from 11 percent to 13 percent.

Still Dixon, the student negotiator during the walkout, said he feels a sense of accomplishment and joy. When he returned to campus this year for the Black Alumni Reunion, he was stunned to see the sheer number of African Americans who are part of Brown’s community.

“But we had to fight for that,” Dixon said. “We fought for it because we felt it was the right thing to do. But it was definitely a fight. It wasn't a gift.”

Letter from the Afro-Americ... by on Scribd

</div>

Archival material is courtesy of Brown University Archives and the Rhode Island Historical Society.</div>

The audio and written versions of this story were done by Gabrielle Emanuel. The video was produced by Emily Judem.