George Herbert Walker Bush, the 41st president of the United States, died Friday, less than eight months after the burial of his wife Barbara.

George and Barbara Bush share with John and Abigail Adams the distinction of not only serving in the White House, but of also having sons who followed in their wake: George Walker Bush was the 43rd president, John Quincy Adams was the sixth.

Bush's death marks the end of a political tradition. Though he was a committed conservative, Bush the elder nevertheless became a prisoner of the historic pivot to the right executed by the Republican Party in the last half of the 20th century. That shift proved to be Bush 41’s undoing, but it buoyed the career of his son.

Bush was a scion of the fiscally conservative but socially moderate east coast establishment. His father, Prescott, was a Wall Street investment banker who became a U.S. senator representing Connecticut. Like most members of that tribe, Prescott Bush opposed the anti-communist fear tactics of Sen. Joe McCarthy of Wisconsin, supported birth control and favored civil rights.

After serving in World War II as the Navy's youngest aviator and graduating from Yale, Bush moved to West Texas with Barbara where he made his first million dollars in the oil business before age 40. He simultaneously planted the seeds of a Republican renaissance in then-Democratic Texas, which is now one of the nation’s most reliably red states.

In 1966, Bush was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, but he later failed to win a U.S. Senate seat. He also did stints as U.N. Ambassador, envoy to China, chief of the Central Intelligence Agency, and chairman of the Republican National Committee.

Bush’s 1980 campaign against former California Gov. Ronald Reagan is now recognized as a watershed election.

The Republican contest pitted the more traditional wing of the Nixon-Rockefeller GOP (Bush) against the sunbelt-based insurgents who worshipped arch conservative Barry Goldwater (Reagan). Bush labeled Reagan’s supply-side economic plan “voodoo economics.” But the massive tax cuts for the rich captured the imagination of rank and file primary voters. They enthusiastically bought the notion that real economic benefits would trickle down from Wall Street to Main Street.

In a shrewd gesture of accommodation, Reagan named Bush his vice president. And once in the oval office, he appointed Bush's political wingman, Howard Baker, to be White House chief of staff.

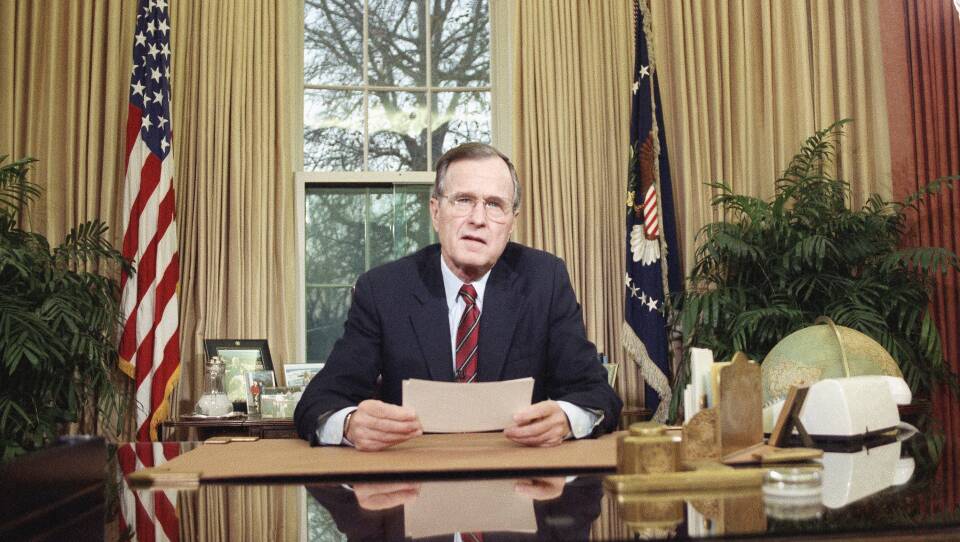

In 1988, Bush extended the Republican hold on the White House for four more years, defeating the Democratic governor of Massachusetts, Michael Dukakis, with 53.4 percent of the vote, carrying 42 states and amassing 426 electoral votes — against 111 for Dukakis. This victory made Bush the first vice president in 152 years to be elected president. Martin Van Buren was the last to hold that distinction.

More important than the size of Bush’s victory was the way in which he won it. During the campaign, Republicans were able to convince voters that Dukakis, the child of Greek and Armenian immigrants and a graduate of Harvard Law School, was an “elite” who would — among other outrages — empty the jails of dangerous criminals. Bush, on the other hand, the product of privilege with a Yale pedigree that ran several generations deep, fashioned himself the exemplar of down-home American values.

It was a neat trick. And it worked, becoming a template for future GOP presidential candidates.

But it was Bush’s successful ability to channel Reagan’s anti-tax fervor that resonated. “Read my lips,” he pledged at the nominating convention, “no new taxes.” When months later, the reality of a deteriorating fiscal situation caught up with him, Bush’s embrace of Reaganomics proved fleeting. He proposed new taxes, thereby wounding himself in the eyes of many Republicans.

Nowhere was Bush's position as a man caught between the new ideological imperatives of the Reagan Revolution and the older, easier alliances of traditional Republicanism more evident than in his two selections to the U.S. Supreme Court. With his left hand, Bush played to the clubby instincts of moderates; with his right, he fed the voracious appetite of those who demanded a conservative counter revolution.

Bush was rewarding New Hampshire Republican Sen. Warren Rudman for his political fealty when he appointed David Souter, a Rudman protégé, to the court. Souter came with a reputation as a tough-on-crime prosecutor who served on the N.H. Supreme Court before being elevated to the U.S. Court of Appeals. Souter's GOP bona fides were enough to trigger opposition to his high court appointment from the National Organization of Women. That, in turn, reassured conservatives who worried that Souter might be squishy on issues such as choice and affirmative action. In the end, Souter turned out to be a stealth justice, who once on the court gravitated to more liberal jurisprudence.

There was nothing squishy about Clarence Thomas, Bush's second Supreme Court appointment. He was a committed conservative. African American, Thomas was born dirt-poor in Georgia. Educated at Holy Cross and Yale Law, Thomas had internalized the sting of most racial prejudice, but was particularly embittered by the professional discrimination he felt from white shoe law firms that were suspicious of attorneys of color because they might have benefited from affirmative action.

A Reagan sub-cabinet appointee, Bush named Thomas to the U.S. Court of Appeals before nominating him to the Supreme Court. The rock ribbed, originalist legal philosophy Thomas espoused, received short shrift during his confirmation hearings, which were dominated by charges of sexual harassment leveled by a former subordinate, Anita Hill.

As with Van Buren, Bush would only serve one term as chief executive, his successes in foreign policy compromised by a shaky and deteriorating economy.

Bush was the only president to successfully wage a war since Franklin Roosevelt. His war with Iraq, dubbed by the military “Operation Desert Storm,” was conducted by an alliance of willing allies, and received solid international approval. Spearheaded by American troops, Desert Storm crushed the forces of Saddam Hussein within days of the first ground attack, evicting them from Kuwait, which had been forcibly annexed.

That Saudi Arabia and Kuwait paid about half the $60 billion tab was icing on the cake.

If the previous 12 years of Bush’s long public life were shaped by forces personified by Reagan, he was forced off the national stage in a battle between generations.

Democratic Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton, the first baby boomer to win the White House, bested Bush in a three-way race that included maverick Texas billionaire Ross Perot.

Even if Perot had not been in the race, it is unlikely Bush would have won. After a dozen consecutive years of Republican rule, the nation was ready for a change.

Clinton proved to be a force of nature, even if unguided and prone to sexual scandal. The generation energized by the 1960s replaced the one that came of age in the 1940s.

In his post-presidential years, Bush's street fighting instincts naturally mellowed. He became something of a Democrat's favorite Republican. Bush and Clinton teamed up for tsunami relief. Barack Obama awarded Bush the presidential medal of freedom.