Study: Lab Leaders Can Make Science Better And Improve Working Conditions

The journal

Nature

recently released a survey of 3,200 scientists that showed many feel science is a friendly and collaborative field, but a sizable minority that says their labs are tense or toxic. The survey also points to several things that universities can do to systematically improve the academic workplace.

Nature’s Senior Editor Monya Baker spoke to us about the findings . She said there are different realities for the people running the labs versus students and post-docs.

One concern: lab leaders are not checking raw data as often as they should be. The survey found that researchers welcome such inquiries by their supervisors.

“Having a lab head check in on raw data is not seen as something that’s hostile; it’d help people do better work,” said Baker.

Another thing that came up in the survey was the idea that lab leaders need more training on managing people and mentoring. Two-thirds of lab heads say they haven’t received training in running a lab or in managing staff.

Baker is familiar with outside organizations offering managerial training.

“They're offered by scientific societies and they’re often oversubscribed and in demand,” she said.

Of the 30 percent who did receive leadership training, “Five-to-one said it was useful,” said Baker. “If you make a supportive working environment, people can do more rigorous research.”

To help improve the quality of research, Nature has instituted a checklist to include more detail about how experiments were done. "The most powerful time to be involved is while work is being done," as opposed to afterword, she said.

Baker said institutions like universities have a lot of influence that they haven’t exercised.

“[Most people feel] they belong to the lab group more than to the institution,” she said. But she said it doesn't have to be that way.

“I think if that changed, you would see stronger science and a more supportive environment,” she said.

Female Bird Song Project

Until recently, researchers thought that most of the birds that sing are male. But in 2016, Karan Odom went through samples of songs from more than 1,000 bird species from around the world and found that

64 percent of the species had females that sing

.

Odom is a postdoctoral research fellow at Leiden University and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. She has launched a new citizen science initiative called the Female Bird Song Project .

Why do we assume that females don't sing as much as males? It has to do with where the most intense study of birds got started — in temperate locations, where birds are more migratory. In those areas, males sing to attract females, and females sing less, probably to avoid predation on the nest. But in tropical locations, both male and female sing a lot.

"If you go to the tropics, a lot of birds are staying in the same place. They have a territory," said Odom.

Both male and female birds must defend their territory and resources, so females and males have similar roles.

Take the male troupials in Puerto Rico, for instance. Odom said she heard males singing at dawn, and they seem to sing to guard or protect females. But female troupials also sing the same kinds of songs and can sing equally complex songs as males.

"Sometimes they sing together in a duet," Odom said. "It's a joint territory defense."

It's a strategy that seems to work as a strong signal to tell other birds to stay off of their territory and away from their resources.

But it’s not only tropical birds. Take your ordinary backyard cardinal. It’s difficult to hear the differences between the male and female song, but both sexes do sing.

The Female Bird Song Project is a citizen-science project. Birders from around the world are asked to contribute. More information regarding how to participate can be found on the project's website .

Where’s My Rosie The Robot? Consumer Robotics Still Has A Way To Go.

Robotics experts will be gathering in Boston this week for the 2018 Robotics Summit and Showcase. It’s an event targeted at professionals, but robots are becoming a bigger presence in all of our lives. We spoke with Steve Crowe, editor of

The Robot Report

, to get a preview.

So, how do you define a robot?

“There’s no universal answer,” said Crowe. “If you took ten of the world’s leading roboticists — you’d have ten different answers."

The writers at the Robot Report follow the paradigm of, “sense, think, and act." So, it’s a robot if it can sense what’s going on around it by seeing and feeling, if it can process what it sees and feels, or if it’s able to act based on information it has gathered.

Crowe also spoke about in increasing popularity of soft robots — robots that are made of soft materials. They have a variety of possible benefits, like the ability to handle fragile things like eggs, or an exoskeleton that can help people walk. It's "bio-inspired engineering that resembles nature,” says Crowe, and says it's an area to watch.

But even with all the robot development happening today, Crowe says, there aren’t a lot of robots in our homes yet. “Besides a vacuuming robot, they’re not close to being here in a useful way,” he said.

A big reason for is that consumer robots can’t yet be produced in an affordable way. Most robotics are heading to manufacturing and e-commerce settings instead. And it’s no secret that those robots have taken manufacturing jobs and other types of jobs away.

But while Crowe believes that while robots may make some jobs obsolete, he said he thinks new jobs will be created.

“We need to make sure people are trained and educated to take those jobs," he said.

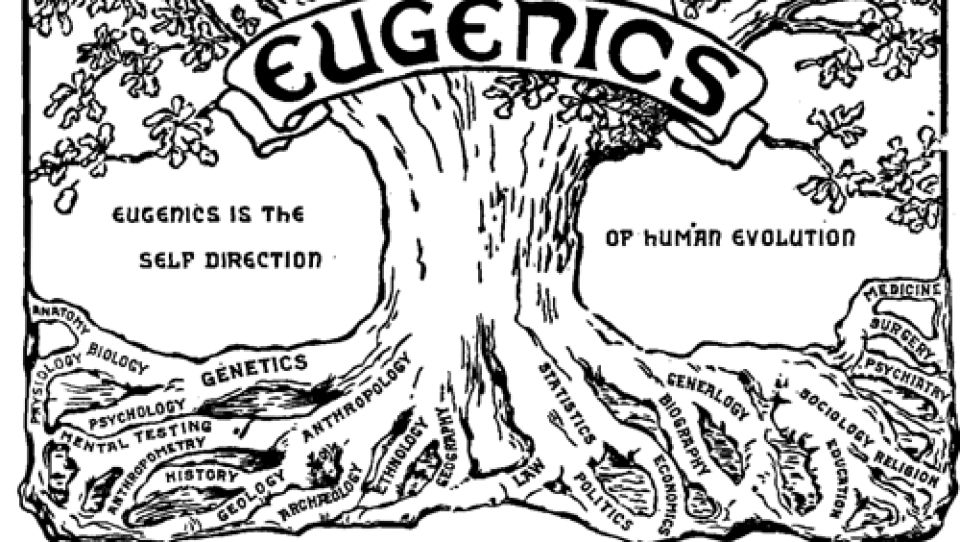

Eugenics And The Early Conservation Movement Are Connected.

Eugenics, which got its start in the 1880s, is a set of beliefs and practices that aims at improving the genetic quality of a human population. It was the basis for forced sterilization laws in the United States and spread to Germany in the first part of the last century.

The American conservation movement started around the same time and was championed by Theodore Roosevelt, who became president in 1901.

It may seem strange today, but those two movements were closely linked at the time.

“I don’t know anyone on either side who denounced the other or said it wasn’t a viable connection,” said Garland Allen , professor emeritus in the department of biology at Washington University in St. Louis.

That includes Roosevelt, who didn’t champion eugenics the way he did conservation, but expressed admiration for the pseudo-scientific field.

“He was very much in contact with all the eugenics people,” Allen said. One common theme between the two movements was the idea of “preserving the best,” he said.

In the early 1900s, elements of the eugenic philosophy were the basis for U.S. state laws on forced sterilization and marriage restrictions. Ultimately, some 60,000 Americans were sterilized. The movement was taken up by the Nazis in Germany and led to the murder of Jews and others deemed to be unworthy.

The conservation movement is no longer linked to eugenics in the public’s mind, but there is fallout from the connection, Allen said.

He sees it in the way that expert opinions are still looked at with suspicion when they come with a strong message of how things ‘should be.’

“The long shadow of eugenics still hangs over conservation,” he said.