Jockey Hill Farm sits high up in the Green Mountains, in the shadow of Shrewsbury Peak. It’s at the end of a long, quiet dirt road.

Tim Stout’s family has owned the 175-acre farm since the 1940s.

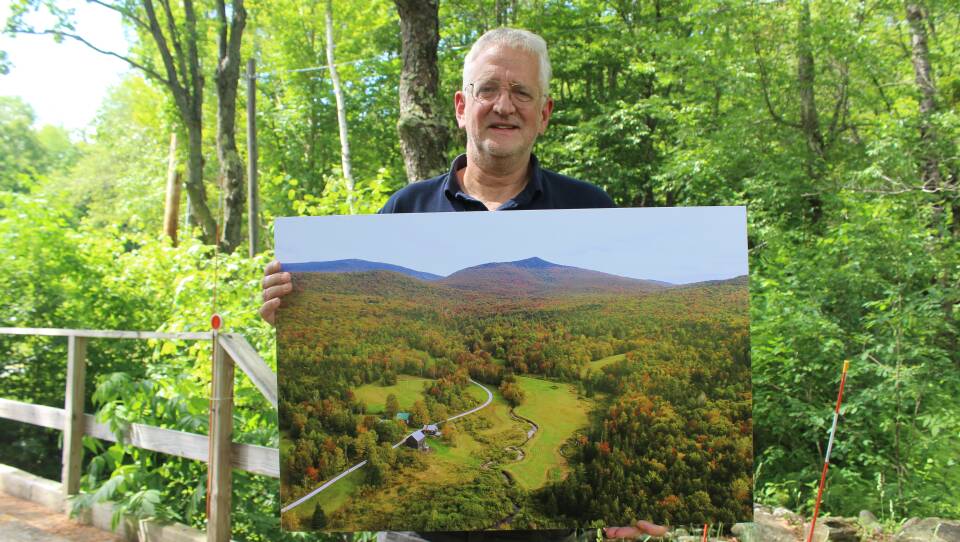

He holds up a map, to show where we are, relative to the neighboring peaks.

“This little knoll here is Jockey Hill, where the name of our farm comes from," he says. "Then, this is little Killington right here …”

Stout is one of the first landowners to enroll his property in a new program from The Nature Conservancy and American Forest Foundation . It’s called the Family Forest Carbon Program .

The idea is to pay small landowners to manage their forests for climate resilience — as well as for carbon sequestration.

This appealed to Stout, who wants to leave this forest in good shape for his young grandkids, and for the planet.

Ultimately, the nonprofits will fund this work by selling forest carbon offsets.

Forest carbon offset markets let landowners get paid for the carbon they store by letting their trees grow old. They’re increasingly popular with companies making public pledges to go carbon neutral, and more are starting to operate in the Northeast.

This work has already gotten started on Stout’s land. He leads the way to a knoll below his sugarbush, where some thinning just took place.

“Up through here, [you can see] how they’ve opened up the canopy quite a bit,” he said. “And they’ve taken a lot of trees down, but there’s still large canopies above, that will grow in further, and there’s still a lot of trees in the understory, that will grow up to fill this gap."

Now those trees that were cut will release carbon into the atmosphere. But the hope is that the older ones will grow bigger and live longer with the new room that’s been made for them. It’s one of two management options landowners can choose from. The other is to simply leave the forest be, and let trees grow old.

Forests store carbon as they grow, not just in the trees but in the soil. Scientists agree the one of the best things we can do to fight climate change right now is to keep forests as forests. It was a key solution called out in the United Nations latest IPCC report . It’s also a key recommendation in Vermont’s Climate Action Plan.

Proponents of carbon markets say they help do just that.

But before you can enroll land in a carbon market, you have to know what’s on it — what you’re starting with. And often, the cost of finding out is too high for small forest owners.

In Vermont, about 80% of our forests are family-owned, and most of those landowners own less than 50 acres of forested land.

The Nature Conservancy reports that as of 2019, less than 1% of the land in forest carbon projects was on properties smaller than 1,000 acres.

And just managing for carbon doesn’t mean you’ll end up with a forest that can stand up to climate change.

That’s where the Nature Conservancy and the American Forest Foundation wanted to do things differently from the way many developers of these projects have operated in the past.

"We don't actually pay landowners for carbon. We fund the program with carbon credits, but we pay landowners for climate smart forestry."Richard Campbell, American Forest Foundation

They worked with scientists and foresters to develop practices that store enough carbon to let landowners get paid modestly and prepare their forests for climate change.

Richard Campbell is a forester and director of landowner engagement with the American Forest Foundation. He helped design the program.

“We don’t actually pay landowners for carbon,” Campbell said. “We fund the program with carbon credits, but we pay landowners for climate smart forestry.”

With the Family Forest Carbon Program, landowners commit to a 20-year contract instead of the usual 50- or 100-year agreement.

The nonprofits also pay for a forest management plan.

And when it comes to measuring how well that plan works to store new carbon on a property, the groups say they’ve designed a process that’s more accurate than what other companies are using.

They say that’s important. Because historically, there have been some challenges with proving that what’s happening in a forest is actually translating to less carbon in the atmosphere.

That math matters, because big, polluting companies are buying carbon offset credits, and telling the public that those credits are canceling out their emissions.

Ali Kosiba is the extension forester for the University of Vermont and was previously Vermont’s state climate forester. She says scientist are conflicted about how best to measure the carbon stored in forests.

“We can very easily measure emissions from fossil fuel combustion pretty accurately,“ Kosiba said. “It’s very hard … to measure carbon in the woods, and especially changes in carbon over time.”

She says not all carbon credits are created equally, because many carbon offset markets are largely unregulated by governments. In those markets, there is no uniform way that project developers measure how much carbon is being taken out of the atmosphere and stored in a forest.

And she says some firms selling credits aren’t forthcoming about how they do their math.

In contrast, Kosiba says the American Forest Foundation and Nature Conservancy have been really transparent.

They’re also having their process voluntarily vetted by a highly-regarded carbon registry called Verra .

Registries operate somewhat like the referees in a carbon market: They set standards that developers can choose to comply with to earn the credits they sell greater credibility.

The organizations say they’ll only sell credits to buyers who can prove they aren’t using them to greenwash polluting activities elsewhere .

That’s not common practice, but because they’re nonprofits, they say they can afford to make less money or even take a loss by being selective about who they sell to.

Kosiba says her concern broadly with these markets has to do with the accounting, but also with the idea that forests in Vermont could be facilitating pollution elsewhere.

“The trading of the carbon stored or sequestered in the forest for actual emissions made elsewhere, I think that’s for me that’s my biggest concern about these programs,” Kosiba said.

Mark Ashton is the director of Yale Forests and a professor of silviculture and forest ecology. He agrees the science is fuzzy, at best, around how best to count the carbon saved by keeping trees in forests — even if we know forests do store carbon.

And he shares Kosiba’s concerns about carbon offsets and environmental justice.

Ashton says that because we don’t really know what climate change is going to throw at New England forests, we’d be wise to manage them the way you might a stock portfolio in an uncertain market.

“So you don’t manage for predictability, you manage for unpredictability,” he said.

Often, he sees carbon offset projects that manage for predictability — for storing carbon and little else. Ashton says the Family Forest Carbon Program is a step in the right direction, towards paying landowners to manage for resilience.

Jim Shallow, with the Nature Conservancy in Vermont, says what we really need is for big polluters to cut their emissions. But in the meantime, he says carbon offsets done right can be a great tool for making progress towards a carbon-neutral economy.

“Right now, we still are a carbon-dependent economy,” he said. “We just don’t have the technologies to make everything carbon neutral. So at this point in the game, we need to rely on nature to help us get to that neutrality.”

The pilot program is open now to landowners with at least 30 acres of forest in western Massachusetts, eastern New York and Vermont. If it goes well, the nonprofits would like to expand it.

So far, more than 300 Vermont landowners have inquired, and TNC says their modeling shows that hundreds of thousands of acres of forest in Vermont could be eligible for the program.

They say in the next couple of critical decades, we need all solutions on the table.