One recent spring morning, Jason Fowler directed his racing wheelchair out of his parents’ driveway in Kingston, Massachusetts. Fowler lives in the urban and busy South Boston where there are more obstacles like cars, people and trashcans to dodge, so he likes to train in the quieter suburbs.

“This back road, there’s just no cars, which is glorious for a wheelchair racer,” he said.

He sits low to the ground in this aerodynamic chair, leaning forward and propelling himself by hitting the wheels’ rims with gloved hands.

“As you can imagine — just like your feet get sore from running — our knuckles and hands get really sore from punching the hand rim after a couple hours,” he said.

This is nothing new for Fowler, given that it will be his 21st time competing in the Boston Marathon. He’s competed in about 50 marathons altogether, and even more triathlons — even winning two Ironman World Championships. But he said Monday’s race will be a special one, because it’s the 50th anniversary of the first wheelchair athlete to officially compete in the Boston Marathon.

Growing up, Fowler was a competitive motocross racer. He broke his back when he was 17.

“Six months after my accident, I borrowed a racing wheelchair from a friend of a friend and started doing road races,” he said.

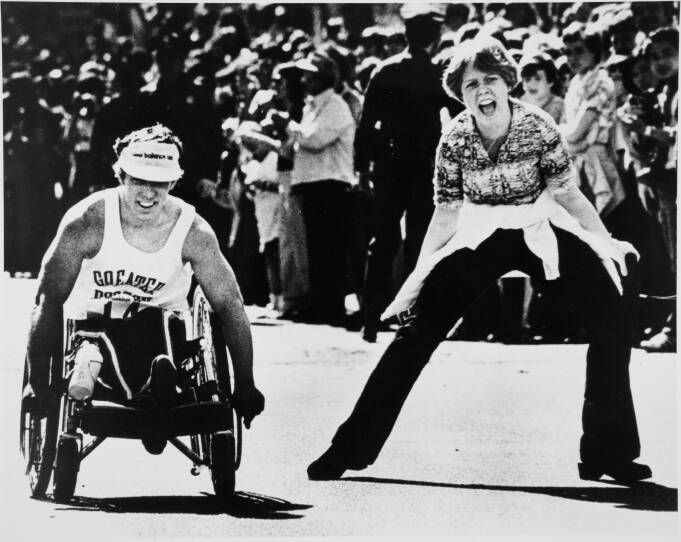

When he was starting out wheelchair racing, Fowler said Bob Hall served as a role model. In 1975, Hall became the first person sanctioned to compete in the Boston Marathon in a wheelchair.

“I always thought I had the ability to do what I set my mind out to, no matter what distance,” Hall recalled. “I wasn’t always good, or wasn’t always winning, but it was always about the challenge.”

It wasn’t Hall’s idea to compete in Boston. He heard some other wheelchair athletes talking about maybe doing his hometown marathon, and a mixture of pride and competitiveness took over.

“If I didn’t do it, someone would have shown up and did it, and that would have been like a catastrophe for me,” Hall said.

The Boston Marathon’s race director agreed to award Hall a certificate of completion if he could finish in under 3 hours.

“I never thought about what I was doing as ‘first’ or ‘unique.’ I was really doing it for myself,” Hall recalled. “I never even thought about the time. It was a ride of enjoyment.”

Even so, Hall beat that 3-hour goal by 2 minutes. And he was using a clunky hospital-style wheelchair, unlike the sleek racing ones used today.

In sanctioning Hall, Boston became the first major marathon to include a wheelchair division. And since that first official race, a half-century ago, nearly 1,900 wheelchair athletes have competed — including Jason Fowler.

“I say competing is in my blood, but for the most part it just makes me a better human,” Fowler said. “It used to be about winning and competition, and now I realize how fortunate I am to be healthy enough to do these things.”