As she dug for clues about her ancestors in the pages of Petersham, Massachusetts’ local history , Jennifer Albertine struck the underbelly of the town her family has called home for 11 generations.

The present-day boundaries of Petersham are nearly identical to those outlined in a 1733 grant , in which colonial Massachusetts carved out a chunk of Nipmuc land, divvied it up into roughly 50 to 100-acre parcels, and doled it out to 72 volunteer bounty hunters as a bonus for scalping 10 Abenaki nearly a decade before.

“A Nipmuc person lost that connection — that connection that I have to the land,” Albertine said. “That’s heavy to think about.”

In 1724, at the request of Captain John Lovewell, the Massachusetts government offered 100 pounds — about the annual salary of a schoolteacher at the time — for each male Native American scalp brought to its council in Boston.

Months later, Lovewell’s men massacred 10 Abenaki next to a lake that now bears his name: Lake Lovell in New Hampshire.

Lovewell trudged to Boston, assured the council the victims were over the age of 12, and paraded their scalps around town before weaving a wig out of their hair and departing for another bloody expedition in Maine.

In the decade that followed, soldiers, bounty hunters and their children demanded land previously promised for over half a century of capturing and killing Natives across New England.

In 1733, the government fulfilled that promise for Lovewell’s men, handing out parcels in an area northwest of Worcester. These lots comprised “Volunteer Town” — a nod to the bounty hunters’ murderous initiative — and in 1754, the town was incorporated as Petersham.

Scalping and genocide

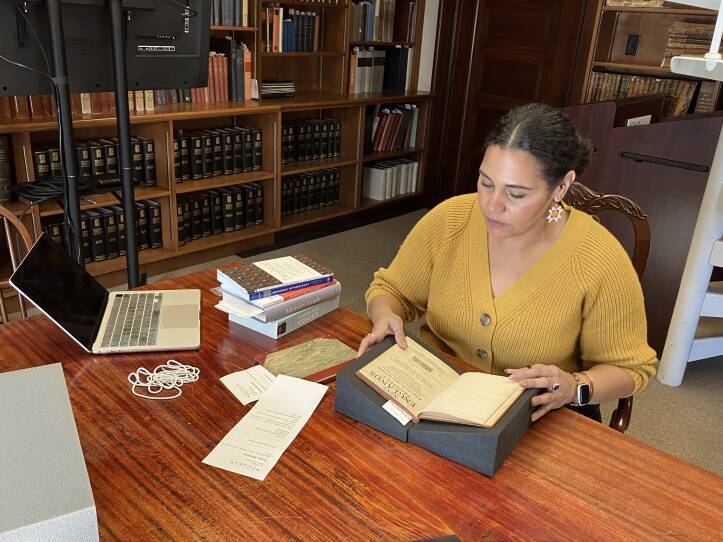

Kimberly Toney grew up a few miles away, in Barre. She is the coordinating curator of Native American and Indigenous Collections at Brown University Libraries and member of the Hassanamisco Band of Nipmuc. Last April, she spoke on Petersham’s formation at its historical society’s annual meeting.

“I got emotional myself, talking about the scalp bounties,” she said.

It’s one thing to push back against the “cultural predisposition in America to think of Indigenous people as being of the past,” she added. “It’s kind of another thing to talk about the very real sanctioned murder of men, women, and children.”

Massachusetts was not the only colony that issued bounties for Native scalps; the practice was pervasive. And since the borders of Massachusetts were much larger at the turn of the 18th century, some of the bounty land is now in Maine and New Hampshire.

After they received land, some of Lovewell’s mercenaries built homes. Others sold. Daniel Spooner and William Negus — who had fought for Lovewell but was not given a land grant — purchased lots, and by 1750, became two of Volunteer Town’s original 55 settlers.

Albertine knows the names Spooner and Negus from her grandmother’s handwritten family tree. A few generations after the two men settled in Petersham, her ancestors, Stevens Spooner and Mary Angela Negus, married.

Historian Kristine Malpica researched scalp bounties and land grants for Upstander Project as the organization produced “Bounty,” a film and accompanying teacher’s guide examining the history of scalping in New England. The nonprofit started in 2009, producing documentaries, educational resources and workshops on systemic and historical injustices and atrocities.

“The scalping was not purely a vehicle of warfare,” Malpica said. “It was a vehicle of genocide.”

And the violence was widespread. Upstander Project analyzed town records, General Court laws and the Journals of the Massachusetts House of Representatives to create an archive of bounty claims. From this archive, GBH News found, in addition to Petersham, the early 18th-century government allocated 800 acres of land in the present-day Massachusetts towns of Hardwick and North Adams, respectively, as compensation for two separate scalpings.

In one of those raids, Colonel Benjamin Church scalped Pometacomet, also known as King Philip. His severed head remained on display in Plymouth from 1676 until at least two decades later.

Other soldiers and bounty hunters were given land scattered around the colony in exchange for murdering Natives. In 1733, the colonial legislature carved seven townships out of Native lands, designating the prospective towns for the descendants of soldiers who fought in Pometacomet’s Resistance — also known as King Philip’s War.

The next year, the government reserved six square miles of land within the boundaries of present-day Massachusetts towns Bernardston, Colrain and Leyden, for the children of the soldiers who slaughtered over 200 Natives in the 1676 Turners Falls massacre.

“It all starts with dehumanization,” Malpica said, “to be able to justify the killing, the scalping of children, of non-combatants, of civilians.”

In sum, Upstander Project estimates millions of dollars and tens of thousands of acres of land throughout New England were given to soldiers who scalped Native Americans. As they encroached on Native land further west, expansionist settlers continued to issue these scalp bounties well into the late 19th century.

“Those rewards are really important,” Hartman Deetz, a member of the Wampanoag Tribe, said, “because it’s what really cements that this is a matter of policy, a matter of intent, a matter of purpose.”

“It’s not ancient history,” Deetz added.

A recent Boston Foundation report found Native American wealth in Massachusetts lags far behind non-Natives, in part because of their dispossession from the lands of their ancestors.

“We still continue to see our lands, our waters poisoned, our resources extracted,” Deetz said. “We see it in life expectancy. We see it in quality of life. We see it in economic disparities.”

Remembering and reckoning with the past

Slowly, towns like Petersham are starting to reckon with their violent past.

Albertine is the climate and land justice director at Mount Grace Land Trust , working to conserve land under cultural respect easements, where Native people have permanent access to the land for ceremonies, seasonal celebrations, camping and more. She is also a board member of the Petersham Historical Society.

“My ancestors benefited from that system,” Albertine said. “I try to recognize that privilege and fight for other people.”

In their Open Space and Recreation Plan a year ago, Petersham community leaders acknowledged the pivotal role the scalp bounties played in the origins of their town. The plan confirms that “As recompense for engaging in Lovewell’s War, a genocidal campaign against the native population” — and “rewarding the pursuit of scalp bounties” — soldiers were granted land, “eventually incorporated as the Town of Petersham.”

“I thought that was really huge,” Albertine said. “They actually dug into the fact that this land was stolen from the Nipmuc people.”

“If you act like it never did happen,” Deetz said, “then you continue to turn away and turn a blind eye for the sake of not wanting to feel uncomfortable.”

For Toney and many Native people, deconstructing colonist-centric, revisionist history often requires mining emotional stores, and unearthing generational trauma.

“But I think at this point in my life, it’s really much easier for me,” Toney said, “because I am here. I have access to all these things.”

She motioned to the books, maps and deeds from the 17th and 18th centuries around her in the John Carter Brown Library.

“Let me show you the receipts,” she said.

This story was produced as part of coursework with Boston University journalism professor Brooke Williams.