Politicians and business leaders have praised Massport’s $60 million project to build electric shore power, reducing dangerous emissions from its growing cruise ship business.

But just months before announcing that plan, the quasi-governmental agency had painted a vastly more expensive and complex project. In its unsuccessful application to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Massport said $196.9 million was the “minimum feasible” cost to accommodate up to two ships at Flynn Cruiseport, according to records obtained by the GBH News Center for Investigative Reporting.

Massport — which controls more than three-fourths of maritime shipping in the harbor — told GBH News on Monday that the difference in estimated costs are due to revisions and trims made to the project since they first pitched it to the EPA in May.

“CEO [Richard] Davey has made shore power a priority as a commitment to our neighboring communities and as part of our net zero [emissions] goals,” Massport spokeswoman Samantha Decker said in an emailed statement. “He asked the team to go back and determine the cost of just the shore power piece.”

Thomas Ready, a board member at the Fort Point Neighborhood Association in Boston, told GBH News that the vastly different proposals should be cause for concern. His organization is worried about health and traffic impacts to the increasingly dense residential community close to Massport’s cruise and container shipping ports.

“We clearly need to get the details right … to inform us as to what exactly is the overall plan down there,” he said. “None of it squares.”

GBH News requested information about Massport’s application to the EPA in October. After the agency failed for weeks to comply with the state public records law, the state Supervisor of Public Records ordered Massport to release a copy of the application.

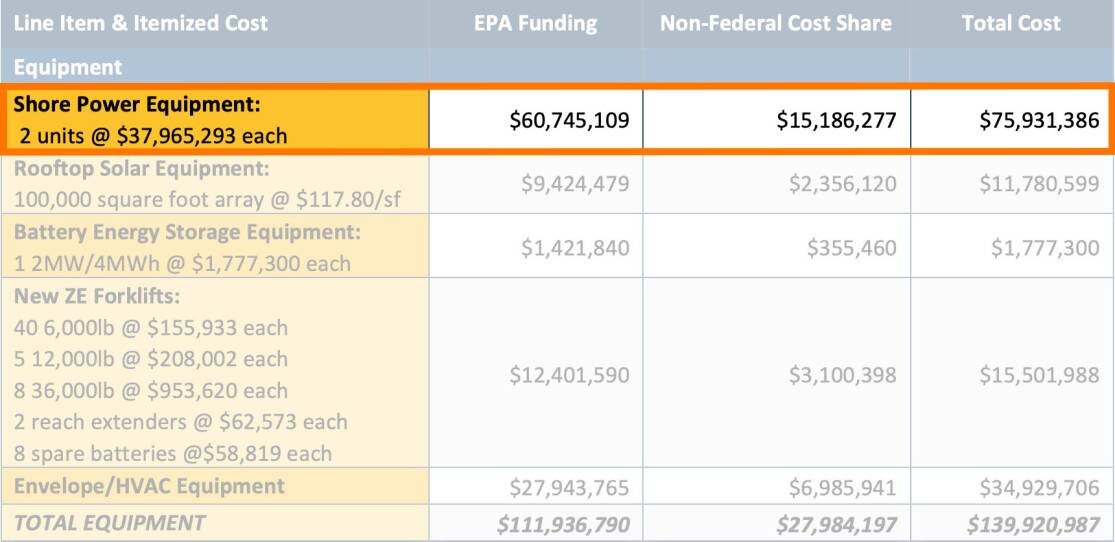

In its response Monday, Massport did not explain how it will be able to construct electrical shore power at two of its terminal berths for $60 million when their itemized budget submitted to the EPA said the equipment alone for two units would cost just under $76 million — with construction estimated to cost an additional $93.6 million.

Massport’s decision to scale back its plans also could make it less reliable during days with peak energy demand. In its original proposal to the EPA, the state said a 100,000-square-foot rooftop solar installation and battery energy storage was critical to provide uninterrupted electric power.

“Spikes in demand for shore power will likely result in capacity constraints, which will lead Eversource to request that shore power be disengaged from the system when overall system demand is high,” Massport wrote in its initial application.

On Monday, the state agency said that that important solar backup component— estimated to cost $13 million — had been scrapped.

Massport also said it is no longer planning $12 million worth of structural repairs to the terminal rooftop, which was supposed to house 16 shipping containers holding hundreds of tons of electrical infrastructure.

“The heavy shore power equipment will need to be relocated elsewhere. The exact location is not yet determined as design is ongoing,” Massport said in the email.

If fully implemented, Massport said in its EPA application that providing shore power for its cruise ship business would cut more than 10,400 tons of carbon dioxide emissions annually. The state agency on Monday said that its revised plan would still reduce carbon emissions but did not specify a target amount.

Massport said it did not request a debriefing with the EPA to understand why its application was not selected. The agency said it plans to look for other grants to support its shore power aspirations.

Shore power for cruise ships also should curb dangerous particulate matter and nitrogen oxide emissions that are linked to premature deaths, cancer and respiratory illness in frontline port communities.

Jonathan Buonocore, an environmental health expert at Boston University School of Public Health, said cutting those emissions would improve health in near communities.

“The benefits of electrifying any big fossil fuel source is that you reduce the emissions in a big source of air pollution in the area,” he said.

But how port operators and communities track emissions has stirred controversy. Massport’s plan to conduct an emissions inventory will primarily look at fuel consumption of ships and heavy equipment at its cruise ship terminal but not actual sensors measuring air quality, also known as fenceline monitoring.

Environmental justice activists in other port communities from Providence, Rhode Island, to Newark, New Jersey, have demanded air sensors for fenceline monitoring.

“Fenceline monitoring would definitely be more useful for the community. There’s no doubt about that,” said Buonocore. “[For] what the community is being exposed to, it is certainly the most relevant for them.”

Scott Hersey, who teaches at Olin College of Engineering in Needham and specializes in environmental justice research, said his air quality sensors in East Boston have detected high levels of emissions coming from Massport’s cruise and container ship terminals.

“The concentration of freshly emitted pollutants are highest when the wind is coming from the direction of the port,” Hersey said in an email. “The port’s impact on local air quality is enormous. It is essential that monitoring happen in the area.”