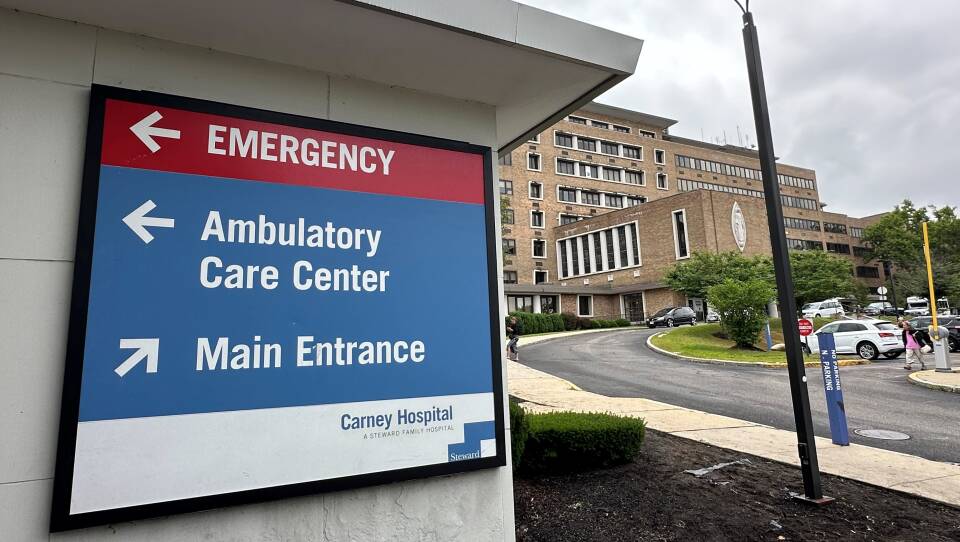

As Steward Health Care gets ready to permanently close two hospitals on Saturday morning, the bankrupt company is also trying to answer pressing questions about how that’s all going to play out.

Steward spokesperson Deborah Chiaravalloti said there are no inpatients remaining at either Carney Hospital in Dorchester and Nashoba Valley Medical Center in Ayer, and that each emergency department had just one patient as of Thursday morning. She said Steward is trying to make sure people know that after 7 a.m. Saturday, they should not show up to either hospital expecting care.

“So, were a patient to show up and knock on the door, there are no licensed personnel inside that hospital to care for them,” she said, “because it is no longer a hospital. It is only a building.”

For the week following the closures, an ambulance will be stationed at each hospital in case anyone does show up in an emergency. An earlier plan provided for ambulances for just a few days, but an ombudsman charged with advocating for patients during Steward’s bankruptcy pressed for that service to be extended . Chiaravalloti confirmed Thursday that they’d be there for the full week.

Officials have also expressed concerns about how the closures will affect patients in the long term.

Stephen Davis of the state’s Department of Public Health on Tuesday wrote in letters to a Steward Health Care official that many of the responses the company had previously provided were “substantively inadequate.” The DPH letter demands more information on how a patient assistance hotline is being publicized and how transportation needs will be addressed for low-income patients to get to other hospitals. DPH also wants more details on a range of other questions, including how patients will be able to access X-rays and other medical images.

Chiaravalloti told GBH News that the company is working on responses to the state’s questions, and would submit responses by the state’s deadline at the close of business Thursday.

“The patient assistance line is being publicized on our website, through social media, through community chambers, community newspapers, and we put it in a letter that went to 43,000 patients. So we are publicizing that extensively,” Chiaravalloti said. “And in terms of medical records, we have also put that into the patient letters. We have posted fliers on all of our hospital doors.”

Patient records will be going to some of Steward’s other hospitals that are being sold. Records from Carney Hospital will be kept at nearby St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center, which is in final negotiations to be sold to Boston Medical Center. Records from Nashoba Valley Medical Center will go to Holy Family Hospital in Methuen and Haverhill, which is being sold to Lawrence General Hospital.

“They are all filed, they are documented, they are all stored according to law in HIPAA privacy arrangements,” she said.

As for the state’s questions about transportation assistance for low-income patients, Chiaravalloti said Steward has purchased 500 mass transit vouchers for Carney Hospital patients that will be distributed by physicians’ offices.

“So that if they are being displaced and they can’t get lab and imaging services at Carney anymore, they can get to another hospital,” Chiaravalloti said. “There is no similar thing for Nashoba Valley Medical Center, unfortunately. We have done extensive research in that area. And, you know, even the chamber [of commerce] out there says that it is kind of a transportation desert. So, while we have researched it, we haven’t been able to provide the same support there.”

Town officials in Ayer say they’ve been frustrated with a lack of communication from Steward about the closure plan.

“There are a lot of questions,” said Carly Antonellis, Ayer’s assistant town manager. “From the Steward management executive level, we have not heard from them, other than what they’ve submitted to the state. And that was lackluster at best.”

With the emergency room at Nashoba Valley Medical Center closed, Antonellis said, the closest option for Ayer residents is UMass Memorial Health in Leominster and Emerson Hospital in Concord.

“Emerson is further, but traditionally doesn’t have the backups that Leominster does. But they still have them,” Antonellis said. “So, our main concern since we’ve heard about this just a month ago: What are we going to do with [town] ambulances? Instead of a 5- to 10-minute run up the hill, they’re gone for over an hour to an hour and a half. So, if we have other calls coming in, we’re going to have an ambulance out of service for a prolonged period of time, which is the town’s major biggest concern.”

EMS response times are also a concern for patients in the Dorchester area with the closure of Carney Hospital.

“Without this hospital, patients in need of emergency care will be transported to other Boston hospitals, some of which are already experiencing capacity issues,” a Boston EMS spokesperson said in a written statement Wednesday. “This is likely to result in increased transport times for patients traveling farther to the nearest hospital as well as prolonged turnaround times for ambulances.”

Boston EMS says they plan to add an additional ambulance in the near future to increase coverage in Dorchester. In 2023, Boston EMS transported 17 patients a day to Carney on average, for a total of 6,313 patients.

Carney Hospital was also home to an ambulance station. Boston EMS says it doesn’t know yet what the future holds for that station. Chiaravalloti said the facility is owned not by Steward, but by its landlord, Healthcare Properties Trust. She said Steward’s facilities management company has connected Boston EMS with the landlord to work out those details.

In a written statement, Dr. Bisola Ojikutu, Boston’s commissioner of public health and executive director of the Boston Public Health Commission, said the city has created a “city-level incident management team” to respond to the closure of Carney Hospital and “make sure that no Boston resident falls through the cracks.”

“We continue to be concerned about access to care, behavioral health, health equity, and emergency response times as this process moves forward. We will keep doing everything in our power to support patients and residents and ensure equitable access to needed care,” Ojikutu said. “At the same time, we need to plan for the future. This site must remain a health resource for the community. Mayor [Michelle] Wu has made it clear that her administration will oppose any effort to use the property for uses other than the provision of healthcare.”