A new report by Worcester organizations working to address hunger shows that many families around New England’s second largest city are food insecure and don’t benefit from local and federal food assistance programs.

As part of the Worcester Community Food Assessment , researchers surveyed nearly 500 people about their shopping patterns and experiences with hunger. More than half of the respondents reported that in the past year they either struggled to purchase enough food, ate less than they should, or could not keep a sufficient amount of food at home.

The survey also showed that households with children were 2.2 times more likely to experience hunger. Residents attributed their food insecurity to being stretched with high grocery prices, exorbitant housing costs and lacking adequate transportation to markets.

“The other major thing is that there are state and federal programs that are meant to support people to be not reliant on daily food programs like food pantries or community fridges. But they’re not sufficient enough to last people through the month,” said Casie Burns, co-chair of the Center on Food Equity, which helped produce the assessment.

Burns noted the survey was not representative of Worcester’s entire population because it included a disproportionate percentage people who are of lower incomes and more likely to struggle with food insecurity. The research occurred last year shortly after the expiration of expanded pandemic era benefits as part of the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program, known as SNAP.

Anti-hunger experts had credited a nationwide decrease in food insecurity from 2020 to 2021 to the extra SNAP money. In Central Massachusetts alone, the emergency benefits added up to about $12.4 million, said Jean McMurray, CEO of the Worcester County Food Bank — which also collaborated on the food assessment.

Since the expiration of the extra SNAP money, McMurray said hunger has soared. The food bank has seen a 32% surge in people needing food over the past year. And although it’s ramped up food distribution by 20% in response, it’s still struggling to keep up with demand.

“This is the worst I’ve ever seen it,” McMurray said. “Food is just going out of our facility so much more quickly.”

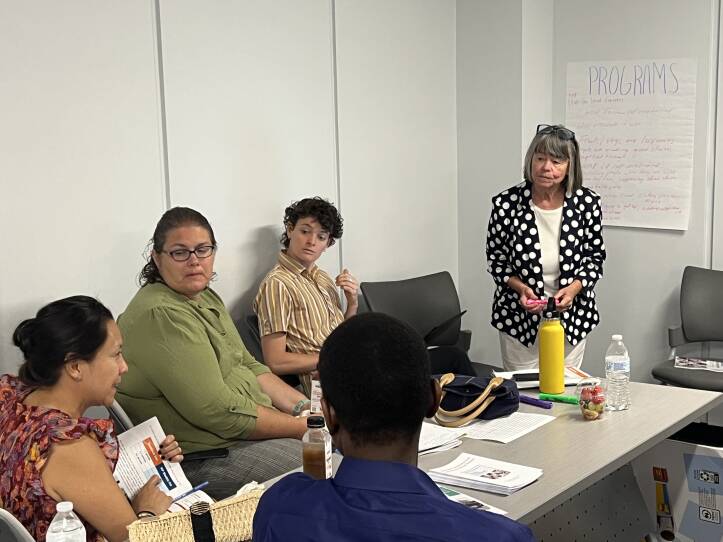

During a presentation on the food assessment Tuesday, U.S. Rep. Jim McGovern, who represents the Worcester area, agreed there was a need for more federal nutrition assistance benefits. He faulted Congress for not doing more to address the issue.

“Hunger, when all is said and done, is a political condition,” McGovern said. “When you tell people in Washington that 44 million Americans don’t know where the next meal is going to come from, you’re kind of greeted with a yawn.”

Worcester anti-hunger advocates said solutions to food insecurity in Central Massachusetts must include advocating state and federal officials for enhanced nutrition benefits, improving public transportation to grocery stores and collaborating with local farms to donate more fresh food.

Any progress could make a big difference, said Laura Martinez, who helped produce the community food assessment and has struggled to access food in recent years. Not only does hunger affect people’s health, she said it takes a toll on their ability to work and be a parent.

She described her past experiences with food insecurity as a daily calculus around timing meals and relying on free coffee to suppress her diet.

“Being poor is a full-time job,” she said. “When you are poor and food insecure, you can’t think about next week.”