Si deseas leer esta cobertura en español visite El Planeta.

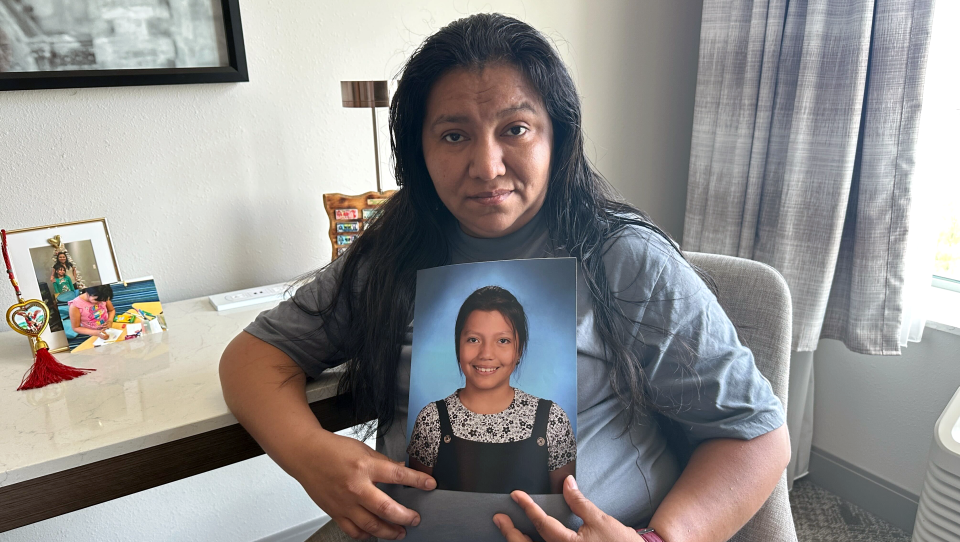

When Dinora left her home before dawn, her 10-year-old daughter Ceydi was asleep in the bed they shared. The hallways of the old building were so dark she’d put the flashlight on her phone to walk down the stairwell.

Dinora was heading to her job at a catering supply company when she received a call. It was “policia.” There was a fire. Her daughter was injured. A colleague took her back to 430 Meridian St., where flames poured out of the windows. She learned Ceydi was already at the hospital.

The six-alarm fire on April 2 ultimately killed Dinora’s child as well as an adult resident, and it displaced 30 people.

Now, three months later, many advocates and former residents see it as an example of how Boston needs to do more to protect people from fires before they happen — and how fractured support services are after the embers are out.

Immigrants face additional challenges navigating the flawed systems. Former residents told GBH News that information provided by the city often wasn’t in their own language, or wasn’t usable — like a list of broken links. There can be further distrust of getting support from the government, particularly for those who are immigrants without permanent legal status. Because of all of these burdens, Meridian Street victims told GBH News they relied on community nonprofits, especially Mutual Aid Eastie, to connect the dots for them.

“There are so many gaps, and so many people fall through the cracks,” said Neenah Estrella-Luna, cofounder of Mutual Aid Eastie. “There’s a lot of improvement that is needed in terms of emergency response by the city.”

Before the fire

Dinora, who GBH News is identifying only by her first name because of privacy concerns, and her daughter Ceydi are originally from Honduras and moved in six months before the fire. They paid $650 a month to share an attic apartment with another woman and man, and a bathroom with others a floor down.

Dinora said Ceydi wanted to be an actor. She and Ceydi spent their time together taking selfies and making videos with Ceydi taking on the role of director, instructing her to walk through the door to their room, describing their surroundings.

“She never wanted to leave me alone,” Dinora said.

The large building at 430 Meridian St. is listed as a single-family home in city records, but a closer look by GBH News shows the property has a long history as a suspected rooming house. The last inspection there was conducted in response to complaints to the city’s Inspectional Service Department in 2015.

Residents told GBH News that they’d complained to the owner, Jose Yanes, and his son about the building’s fire alarms needing batteries, and the single lightbulb sparking constantly in the bathroom. They also complained about having to pour buckets of water over their heads in the tub because the shower didn’t work.

The fatal April fire was caused by a short circuit in the basement, according to the fire department’s investigation obtained by GBH News. The report states that William Yanes, one of the owner’s family members, said he awoke to smoke and unsuccessfully tried to put out the fire with his hands. Responders later found a space heater and an “array of cords” connected to an outlet adapter.

Neither Jose nor William Yanes responded to GBH News’ attempts to reach them for comment.

East Boston City Councilor Gabriela Coletta Zapata has seen multiple fires destroy triple-decker homes. She said, in East Boston, “our fires have been acutely devastating.” She attributes that to a number of factors: the homes here are older, packed densely, and many don’t have sprinkler systems because of their age.

“But then another added component into all of this is the fact that East Boston is at the center of the displacement crisis,” Coletta Zapata said.

In many instances, a whole family will live in one bedroom to be able to afford rent — exactly the case at Meridian Street. These families are a fire away from losing everything because of unsafe building conditions and precarious financial situations.

“They [rooming houses] are a symptom of the larger housing crisis that made it so difficult to attend to the housing needs of the folks affected by these fires,” said Estrella-Luna. “Especially the people at 430 who had much fewer resources than the people living next door.”

Initial response

Diego Rabelo was home next door, at 432 Meridian, when the fire broke out. He woke up, heard yelling next door and saw the smoke billowing.

He banged on his neighbors’ doors while his mom and two sisters found their dog and cat and evacuated to the street. A while later, they went to a community room at the Shore Plaza apartments, where city officials and nonprofits like the Red Cross went to talk to fire victims.

Paul Hoy, a 12-year volunteer with the Red Cross in Massachusetts, said one of the first things his disaster services team does is try to determine whether all the residents have been accounted for.

City officials and nonprofit organizations that GBH News spoke with all emphasized that visa status is not an issue when providing support to fire victims. Hoy said the Red Cross needs to establish residency to be able to distribute financial assistance and open cases for impacted residents, but that “we’re not worried about who’s on the lease.”

Though the city compiled their own list of those impacted, Estrella-Luna of Mutual Aid Eastie told GBH News that the group identified a half-dozen more displaced residents than the city, as confirmed by Coletta Zapata. This list was not shared with the group to cross-check until about 10 days after the fire, Estrella-Luna said.

Dinora was one of the residents who “was literally this close to falling through the cracks,” from receiving initial services, said Coletta Zapata, as she spent time with her daughter at Massachusetts General Hospital. Smoke inhalation had put Ceydi into cardiac arrest, and she was in a coma.

Mayor Michelle Wu spoke with Dinora herself while she sat at her daughter’s bedside. The mayor’s office told GBH News that a litany of city offices responded to the fire — including the Office of Neighborhood Services, the Office of Housing Stability, Boston Public Schools, the Office of Housing Stability and the Office of Emergency Management — “to ensure that families receive the appropriate care, support, and are connected to resources to rebuild their lives after this tragic event.”

Rabelo said government officials handed out business cards immediately after the fire. He also received an email with information about multiple city agencies to reach out to. But he said it had “a lot of old links that didn’t work.”

Fire victims were offered beds at shelters if they needed housing immediately. “I know what the shelters are like — it’s not where you want to go,” he said.

Later in the day, Rabelo got a moment to go back inside his family’s apartment. Rabelo, who is in the military, recently finished his degree at Suffolk University. Now his family’s home of 19 years was covered in soot and water damage. He and a family member grabbed photos, phones, an urn and documents. The owner of his building connected him to a friend who let them stay in their family room for a couple weeks. Rabelo worked with his apartment insurer to get documentation of the fire and funds, finally allowing the family to rent a couple rooms in a Residence Inn as they figured out next steps.

Rabelo has been to the apartment again to try to salvage clothes and other belongings not too damaged by the blaze.

“I definitely feel like we’re starting from zero right now,” he said.

Dinora was left with even less.

After nearly two weeks in a coma, Ceydi was disconnected from life support on April 13.

Dinora tried to go back to 430 Meridian, hoping to get documents and photos for Ceydi’s death certificate and memorial. But she says the landlord refused to call fire officials to let her inside. Instead, Ceydi’s prayer cards for her funeral were printed with a yearbook photo that school staff retrieved. She stayed on a cousin’s couch for a few days while shouldering immeasurable grief — and confusion about what would happen next.

The months afterward

There was no shortage of organizations stepping up to help victims of the Meridian Street fire. Though the Red Cross helps on the day of the disaster, they also open cases to provide services to support those impacted for weeks to come. East Boston Social Centers created a link to a fire fund, which Mutual Aid Eastie led in disbursing. Individual GoFundMe campaigns also began to crop up.

“I’ve been hearing a lot of gratitude also for the way that people have stepped up, which I think it’s reflective of this community,” said Justin Pasquariello from East Boston Social Centers. “We’ve got a tight-knit community and we have people who are impacted by this fire who’ve done a lot to support this community.”

Mutual Aid Eastie confirmed $48,000 was raised through the fire fund to distribute to those who had been displaced.

Mutual Aid Eastie provided Rabelo and other fire victims with funds from donations, and connected him to NeighborHealth, formerly known as the East Boston Neighborhood Health Center.

“The loss of a fire is just horrendous and you lose everything,” said Mimi Gardner, vice president and chief equity officer at NeighborHealth. “And a lot of times you just have the clothes on your back.”

Gardner said the organization has assisted in providing mental health support and resources for those impacted by the Meridian Street fire, as well as help with finding housing and furniture, and giving gift cards for food and transportation.

“The people that really helped me with the housing was actually the neighborhood health clinic,” Rabelo said.

He said no one from the city reached out to assist him at all, even though he later discovered city records listed him as being contacted. He said at some point he did try to get in touch with the city, but “nobody reached back out.”

“I definitely feel like the city could have done more,” he said.

One month after the fire, a housing manager at the health clinic helped connect him to two more nonprofits: East Boston CDC and Neighborhood of Affordable Housing, a social services organization. Diego, his mother and sisters moved into an affordable apartment in East Boston about a month ago as a result of their help.

And, several weeks after the fire, Rabelo learned through the health center about the state-run Residential Assistance for Families in Transition (RAFT) program, and was able to qualify for $7,000 in assistance for rent at the future spot his family is hoping to get through yet another housing nonprofit, Metro Housing Boston. He said he wishes he had known about all of this much sooner after the fire.

Amid the pain and grief of losing everything, those displaced were tasked with the immediate need of finding a new place to live. And in a time where Boston rent prices are among the highest in the country, and emergency shelters are at capacity, it leaves displaced residents in an even tougher position.

Danielle Johnson, the director of the Office of Housing Stability with the mayor’s office, said her office picks up where initial support leaves off, trying to connect residents with city-contracted hotels or working with the landlord to figure out which part of their homeowners insurance can be utilized for tenants.

After a fire, she says her office is also limited in what it can do if a resident’s income is high enough: above 80% of the median income in the city. In those cases, they may only be able to provide a list of housing resources.

Rabelo said that, despite the difficulties, his family was fortunate: he had renters insurance, to which the company added his mom and sisters retroactively; and they had friends offer temporary places to stay.

In the days after the fire, Mutual Aid Eastie saw residents from 430 Meridian sleeping wherever they could.

“One of the folks who was displaced for a few nights was actually sleeping on the floor of the restaurant that he works at,” said Estrella-Luna. “And this was not the first time that something like that has happened.”

For the next fire

At a Boston City Council budget hearing in May, Coletta Zapata asked fire commissioner Paul Burke if the department has Spanish-language fire prevention materials. He answered that he didn’t believe they had any.

The councilor mentioned the Meridian Street fire as an example of a boarding house-caused problem, and asked for more fire prevention materials in Spanish to tell people how it can be hazardous to put too much stress on your electrical system, and provide more smoke detectors. Burke said he was open to the recommendation.

The city is currently in talks with the Boston Fire Department to expand multilingual outreach on fire prevention. It’s also working on implementing a “revolving fund to provide support for victims in a more efficient manner,” according to Coletta Zapata’s office.

There was $100,000 in seed funding for a fire victims’ pool in the city’s fiscal year 2025 budget, but it didn’t garner enough votes from councilors on Wednesday.

“While our efforts to provide initial funding to help fire victims was unsuccessful, this isn’t the end of our advocacy,” said Coletta Zapata. “I’ve urged the administration to develop a fire fund, better coordinate immediate emergency response, and provide adequate support in the months after this devastating life event.”

State Rep. Adrian Madaro, who represents East Boston, said those involved in providing support are also working to evolve to have a more coordinated response.

“I think the ideal thing would be one central point of contact for the families, because I think that’s the easiest thing for them,” Madaro said in an interview with GBH News. That way families won’t have to re-explain the trauma to multiple organizations.

“It’s just about streamlining everything, right? Because at the end of the day, the more we can make the process efficient, the better we can support the families,” said Madaro.

For the past couple months, Dinora has been staying at a hotel with the help of Red Cross and Mutual Aid Eastie funds, and additional help from the city in June. Through the East Boston CDC and Neighborhood of Affordable Housing, which Mutual Aid Eastie connected her with, she qualified for an apartment. But the move-in date’s been pushed back: she’s still living in a hotel.

“It was very difficult,” she said.

The victims themselves want changes so that no one else has to endure what they’ve been through. Rabelo and Dinora both want the city’s inspectional services division to be more involved with complaints about questionable housing to prevent a fire before it burns.

Rabelo said a neighbor complained about 430 Meridian’s conditions twice since 2020 — something the city has no record of. Boston’s Inspectional Services Department provided GBH News with records but didn’t comment further.

“The thing that upset me the most about that one is I feel like the city doesn’t do enough to maintain the codes for the buildings,” he said, adding that the building often had many different people going in and out, fitting the last recorded rooming house complaint.

“I want the city to send inspectors — I want them to be more careful, to audit and check each apartment, because landlords are careless,” Dinora said. “All they want is to collect the rent, and not maintain their properties.”