At 58, Jane Walsh has called Hyannis home for much of her adult life. She moved to the community at 19, made friends, joined boards, raised a daughter who’s now 17, and opened a funky gift shop on Main Street.

But in recent years, she’s felt besieged by a range of unexpected health issues.

Walsh developed high cholesterol, “which was never a problem for me, and nor is it in my family.” She also was diagnosed with thyroid disease (“I actually had a cat that had it as well”). And most recently she was hospitalized with pancreatitis, though she says she eats well, doesn’t drink alcohol, and doesn’t take any medication associated with pancreatic problems.

“And the doctors were like, ‘We don’t know why you had it.’ So yeah, I’m definitely concerned for my health,” she said. “I’m a single mom, and, you know, I can’t let anything happen to me.”

Walsh is one of 426 Hyannis residents or former residents who recently took part in the Massachusetts PFAS & Your Health study , led by the Silent Spring Institute as part of a national effort to learn about how the so-called “forever chemicals” are affecting the health of individuals.

As a result of her participation, Walsh learned that her blood levels of PFHxS – one of the 14,000 known types of PFAS chemicals – are dramatically high. The national average is 1.2 parts per billion in the blood – a relatively tiny amount that’s comparable to 1.2 droplets in an Olympic-sized swimming pool. Americans whose blood contains 3.8 parts per billion are in the 95th percentile. Walsh’s blood contains 18 parts per billion, or 15 times the national average.

As far as Hyannis residents go, Walsh isn’t alone. Researchers from the Silent Spring Institute revealed this week that, among residents who lived in the community over a recent 10-year period, blood levels of PFHxS were about 3.2 times higher than the median for the general population. Those researchers are now beginning the work of understanding the link between PFAS exposure in drinking water and specific health effects.

For Walsh and others like her in Hyannis, the findings are awakening them to the troubling realization that the place they’ve long called home has been serving them and their loved ones poison through the water pipes.

PFAS linked to a range of health issues

Launched in 2020, the Massachusetts PFAS & Your Health Study is one of seven projects funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. It’s part of a national effort to investigate communities across the country, including Hyannis, that have been affected by PFAS contaminants in drinking water.

The chemicals have been linked to changes in thyroid levels, cancer, fertility issues, preeclampsia among pregnant women, decrease in birth weights, developmental effects and a range of other problems .

“Exposures to PFAS have been linked to increased cholesterol and increased risk of obesity. PFAS have consistently been linked to effects on the immune system and, in particular, reduced antibody production by children,” said Dr. Laurel Schaider, the study’s principal investigator and a senior scientist at Silent Spring Institute.

To gain a deeper understanding of effects on specific populations, researchers enrolled participants who lived in Hyannis between 2006 and 2016 in the study. The 10-year window dates back to the time when Hyannis began treating drinking water for PFAS.

At Barnstable Town Hall on Monday, researchers held two outreach sessions with community members where they presented and contextualized the results.

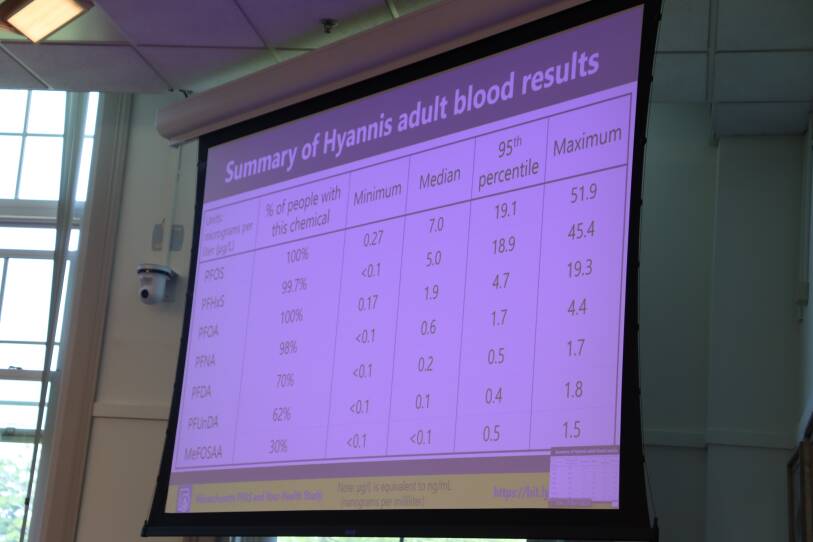

“There were four chemicals that were found in nearly all of our participants: PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS … and then PFNA,” Schaider said. Her team tested for seven types of PFAS.

Researchers found that levels of PFAS were slightly higher in men than women. (This is in line with findings that menstruating women shed blood more frequently and consequently lower their PFAS blood levels). Across all genders, the oldest adults, aged 65 and up, had blood levels of PFAS that were two to three times higher than the youngest adults, aged 18 to 44.

“And then we also compared children ages 4 to 17 to the adults who took part in our study,” Schaider said. “And we did see, particularly for PFOS and PFHxS, that adults were about three to four times higher compared to children.”

Schaider also compared the results from Hyannis to blood levels in the rest of the county. Silent Spring Institute relied on data from a National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey , which samples 5,000 U.S. residents every two years.

“The greatest difference that we see is for PFHxS,” Schaider said. “The median in Hyannis was about 3.2 times higher than the median for the general population.”

Levels for PFOS were also above the median. “But there was less of a difference,” she said. “So the level was about 10% higher than for the general population.”

For PFOS, Hyannis residents had an average of 5.2 micrograms per liter in their blood, while the average American had 4.7 micrograms per liter.

When all the measured PFAS were added up, researchers found Hyannis has a higher proportion of adults with blood levels over 20 parts per billion than the general population— about 38% vs 13%, or nearly three times the proportion. That’s the highest risk category, which experts say should be met with more intense screenings with clinicians.

That includes prioritizing screening for dyslipidemia with a lipid panel, conducting thyroid function testing, assessing for signs and symptoms of kidney cancer, testicular cancer, ulcerative colitis and more.

"I've lived and or worked in Hyannis almost my whole life," said Betsy Young. "It’s like this stuff was just contaminating us."

Schaider said the Silent Spring Institute is now trying to build on the research.

“We’re working now to reconstruct past levels of PFAS in the drinking water in Hyannis and trying to go back in time and to estimate what people’s exposures and blood levels were in past years, to get a better sense of the sort of chronic effect of exposures over time,” she said. “And we will plan to provide updates to the community, as we learn more.”

As a scientist, Schaider said, she has to balance the findings with her feelings.

“It is upsetting when I think about the fact that people in their everyday lives, living in a community here on Cape Cod, got exposed at above-average levels to these toxic chemicals,” she said. “It’s frustrating to me because the companies that manufactured these chemicals knew early on that they could cause harmful health effects, and they kept making the chemicals, and they were not transparent about what they knew about toxic health effects. So these exposures could have been avoided if we had known about them earlier.”

Now, she said, locals have to worry about their own health, and whether these exposures will affect them or their loved ones down the line.

PFAS: how they enter our homes and bodies

PFAS chemicals are a feat of modern engineering. Since the 1940s and ‘50s, manufacturers have been using them to help products resist degradation. They’re essential for items like surgical tools, syringes, and catheters not to be susceptible to heat, friction, and other forces. Manufacturers also found it highly profitable to make consumer products that – with the same chemicals – can be marketed as oil-, water-, and stain-resistant.

In time, health problems were increasingly linked to those chemicals.

Though manufacturers knew of the dangers for years, PFAS only emerged as common drinking water pollutants around 2010-2015. Shortly after, PFOA was phased out of production. But it’s been replaced with other PFAS chemicals that perform virtually identically in carpets, upholstery, waterproof apparel, grease-proof food packaging, cosmetics, paints, and more.

Now, PFAS chemicals are found in the blood of more than 99% of Americans, and humans continue to be exposed to the chemicals through eating, drinking, contact with skin, and even breathing in some cases. And once they enter the human body, they rarely leave.

“They can circulate in our blood for years,” Schaider said. Some newer types of PFAS exit the system in weeks or months, but it’s hardly a win for health.

“[It] is better than years, but it’s still quite a long time considering that other types of chemicals can be cleared from our body in hours,” she said. “And then for other types of PFAS we don’t really know about how long they can stay in our bodies.”

In Hyannis, experts believe, the extremely high levels of PFAS found in blood samples were caused by exposure to drinking water contaminated by firefighting foam.

For decades, the PFAS-laden foam was used at the Barnstable County Fire Training Academy and Barnstable Municipal Airport (now the Gateway Airport). Because of the Cape’s sandy, porous soil, it traveled with ease into the aquifer that provides the region with its drinking water.

“PFOS and PFHxS are two PFAS that are typically found at higher levels, relative to the general population, in areas where firefighting foam is the source of contamination, because these are chemicals that were abundant in those classes of firefighting foams,” Schaider said. “And so what we saw was that these were the two chemicals that were present at the highest levels in our study participants.”

The state and Environmental Protection Agency have more recently established limits on some PFAS chemicals in drinking water and town officials emphasized that Hyannis started filtering tap water in 2016 to remove PFAS; but from 2013-2015 Hyannis had higher levels of PFAS than any other water supply in Massachusetts.

“There are still lingering concerns about past exposures,” Schaider said. “And there’s an opportunity to learn from those past exposures.”

Next steps for study participants

The health problems linked to PFAS exposure are increasingly being studied, but at the moment there’s little information for individuals who want to know what health issues they might face personally, or whether anyone can be held responsible .

“It's frustrating to me because the companies that manufactured these chemicals knew early on that they could cause harmful health effects, and they kept making the chemicals," Laurel Schaider said. "These exposures could have been avoided if we had known about them earlier.”

For Hyannis resident and study participant Betsy Young, one thing is clear: her blood levels of two PFAS chemicals that are found in the firefighting foam are well above the 95th percentile, and health problems have begun.

“My cholesterol is elevated. And I eat a reasonably healthy diet. My doctor has me on a statin to lower my cholesterol. I don’t really have a family history of high cholesterol. … I have my thyroid checked because that’s one of the things. I have a son that had ulcerative colitis, which is something to check for,” Young said. “So there are sort of some things that it’s hard to pinpoint if that’s the reason, but it’s a reason to be concerned.”

Now, she’s left with the task of dealing with consequences. The way Young sees it, fear can either spring people into action, or cause them to freeze. She’s picked the latter, forming a PFAS Citizens Working Group through her post as president of the Greater Hyannis Civic Association to inform her community about the dangers of the chemicals. But it hasn’t been easy.

“When I was leading meetings to try to get people to come and get their blood tested, a lot of people said, ‘I don’t really want to know.’ It’s like it’s almost too scary to find out, which is really kind of sad,” she said. “I think knowing is better than not knowing.”

On the advice of the Silent Spring Institute, she turned to her doctor. Medical professionals are increasingly working with patients to manage the risks of PFAS exposure.

“I went to my doctor and said that I participated in the PFAS test,” Young said. “And she said, ‘Oh, what’s that?’ You know, like there’s just a level of ignorance out there that’s not their fault. It’s just not a well-known issue.”Young said she also tries to avoid products that could add more PFAS to her system.

“But not a lot of them will say on the label what they have,” she said. “Almost every single dental floss has PFAS in it. Most nonstick cookware have it, you know, so it’s things that we’re using in our house every day.”

During a question-and-answer session with Schaider, Young asked about the possibility of “therapeutic blood-letting” to lower the levels of PFAS in her blood.

Schaider said she primarily recommends the avoidance route – selecting products without stain-, oil-, or water-resistant promises – she noted that there’s evidence that supports Young’s idea.

“There was a study in Australia a year or two ago that looked at phlebotomy, and found that donating blood did lower the levels of PFAS in the firefighters in that study,” she said. “I don’t think we’re at the point where a doctor would prescribe that. I think we don’t know yet how many times you would donate blood and how much of a difference that would make. And there’s obviously a risk involved with donating blood as well. But in theory, that would work.”

Jane Walsh said she was already trying blood donation as a potential remedy.

“I contacted the Red Cross and said, ‘Look, I have these high levels. You know, I’d like to get this blood out of me. And, you know, basically, will you take it, you know, even if it’s just for research?’ And they wanted my blood. They’re like, ‘Look, you know, the small amount we get from you could save somebody’s life. You know?’ So now I’m donating blood every 12 weeks, which is as often as you can go.”

If it means staying healthy for her daughter, Walsh said, it’s worth it. But it doesn’t change the sharp jab of reality.

Copyright 2024 CAI