One of the most critical health care jobs and lowest paid is the nursing assistant, which is also called a nurse aide or a home health aide.

In western Massachusetts and elsewhere, there’s a chronic shortage despite efforts to provide training and bump up the pay.

Many immigrants with experience could alleviate the shortage, but a state certification test is a huge barrier.

'They are really hard to fill'

At a health care job fair at Greenfield Community College in February, Dean of Nursing Melanie Ames Zamojski said the biggest labor gaps are in jobs where hands-on care is required, including certified nursing assistants or CNAs.

“People get uncomfortable working so closely with people,” Ames Zamojski said. “If they don't have that experience in taking care of their grandmother or a family member who had been sick, they may not be very comfortable in touching somebody.”

These jobs are a key part of a medical team. Because aides work so closely with patients, they notice changes and will update a nurse.

But Ames Zamojski said CNAs are among the hardest to retain.

“They’re probably the lowest paying job for the amount of work that they do,” she said.

According to a report by the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission , about 90% of direct health care workers in the state are women. That includes CNAs and home health aides. Sixty-one percent are people of color and nearly half are immigrants. Some leave the job for better paying work outside of health care or because they don’t see a path towards advancement.

Inside the job fair, Emma Hudgik is sitting behind a table full of loot to attract potential employees. She is the Greenfield office manager of O’Connell Care at Home.

“We got whoopie pies, gum, magnets, lip balm, and these are sunscreens,” she said.

Hudgik said she would love to hire about 10 aides today — home health aides, not state certified — to care for people at home, such as a patient who has had a fall.

“And they no longer are able to walk on their own, do basic things like go to the bathroom. So then you're doing, more in-depth personal care for them,” Hudgik said. “And it can be difficult.”

Even more difficult for these home health aides, which Hudgik calls “rock stars,” is the pay.

“We typically start with no experience at 16 and we go up to 18 or 19 [dollars] an hour,” she said.

That’s the kind of pay also offered for entry level retail jobs in the region.

Across the room, Lindsay Whitaker, clinical liaison of Highview of Northampton, hires only state-certified nursing assistants or CNAs, with starting pay at $22 an hour. She said Highview has have every shift basically covered.

“To get by, but that can be challenging,” she said. “Of course, if you have a couple of call outs what are you gong to do?”

A “call out” is when an employee calls in sick.

“I think hiring one today would be a really big win for the facility,” Whitaker said. “Anything. Any employee would be a win.”

Kalise Anthony, who has been a CNA for three years, said understaffing is the norm at every facility she has worked at the last few years.

“They are really hard to fill,” Anthony said about CNA positions. “Because they are undervalued.”

Anthony said it's hard — emotionally — when a patient dies. She often works with elderly patients.

“There's also a side to the job that's disgusting and that people don't want to do,” she said.

By that, she means personal care.

“It doesn't really bother me, but that's just my personality,” Anthony said. “I've worked with people and had them walk right out on a shift because they didn't want to do it, because it was too much work. And we only had two CNAs. So, being understaffed as well, puts extra work on the people that are there.”

Besides the pay, having access to child care or reliable transportation is a challenge.

'I want to do more. I want to help.'

In western Massachusetts, the percentage of vacant positions is about 27% — double the other parts of the state, according to Tara Gregorio president of the Massachusetts Senior Care Association.

“The urgency to focus in western Mass. on growing and employing CNAs cannot be overstated,” Gregorio said.

In the western part of the state, Berkshire Health Systems offers supervised training in their own facilities and at Berkshire Community College.

Baystate Health offers training with Holyoke Community College.

Integritus Healthcare offers a hybrid CNA training that includes academic study online and supervised clinical training at facilities in North Adams or Lenox.

Greenfield Community College has a tuition-free CNA course, funded by the state. For the first time, it also includes English language instruction.

Not having strong English skills can be an obstacle to getting certified, even though there are many immigrants who want to pass the test so they can do the work.

Sandra Maria Varela wants to be a CNA. She is a U.S. citizen who immigrated from Portugal and grew up in Cape Verde. Two years ago, she took English language and nurse aide training offered through the Center for New Americans in Northampton.

Varela used to work as a housekeeper in a nursing home, where she noticed the needs of the patients.

“I saw the patient — the people in the wheelchair need a push, need food, need help,” she said. “And I said, 'I want to do more. I want to help.'”

When she was growing up, Varela helped take care of her grandmother.

“And when I help, I feel so happy. And then I want to do more. And all the time I think about my English and I say, 'No, this job — you need English,'” she said.

After the training, she passed the clinical part of the state exam, which requires students to demonstrate proper procedures for caring for patients. But when she took the multiple-choice computer test, in English, she failed twice.

She hasn’t given up.

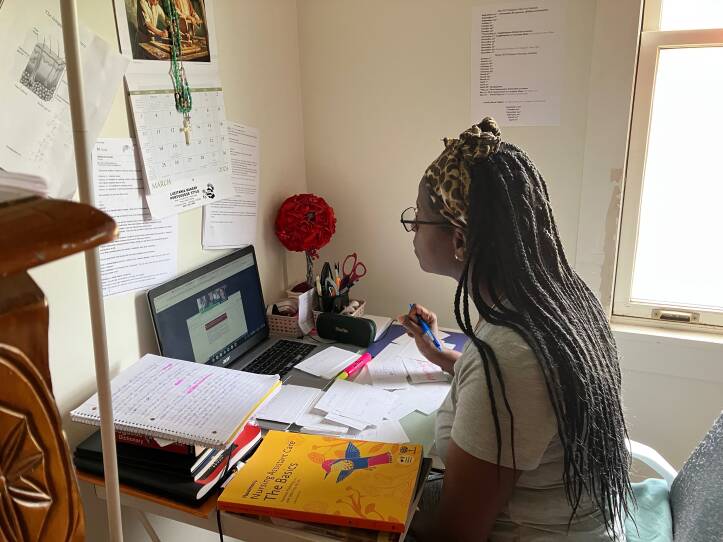

Besides working full-time as a cook, and on Sundays as a companion to a nursing home patient, Varela also meets regularly with Alice Levine, who is teaching her literacy skills.

On a recent Saturday, on Zoom, Levine pointed out the tricky wording of some of the questions on the state exam.

“This is a backwards question because it says 'not,'” Levine said, reading from a practice exam. “'Residents with Parkinson's disease would not have a slow gait, flexible muscles, the tremors or rigid muscles.'”

'The heart that it takes to do this job'

The way the questions are worded trips up a lot of English language learners — even a multi-lingual, experienced nurse like Asani Furaha.

“I don't understand. I failed.” Furaha said. “When I failed, I said, 'How I will do?' Because I need to get my certificate.”

Furaha, a U.S. citizen, was a refugee from the Democratic Republic of Congo, where she was a registered nurse. She worked for Doctors without Borders in Burundi. She speaks several languages including French, Swahili and English.

Passing the clinical test was no problem.

“Because I was a nurse, I know how to take care [of] everything,” Furaha said. “I passed the first time.”

But the other part of the exam, given in English on a computer, Furaha took again and again and again — passing on the fourth try. She is working now as a CNA in two facilities.

Her next goal is to become a registered nurse in the U.S.

Some solutions in the works

Joni Sexauer, a registered nurse, runs a study group for immigrants who are preparing for the CNA exam. She said they have “the heart that it takes to do this job.”

“As a society, we have an obligation to help people succeed, particularly immigrants,” Sexauer said, “who are more than willing to work at a job that isn't desirable to a lot of people.”

And, she said, society desperately needs them.

“We don’t have enough and we have people that are willing to do it that we are throwing stumbling blocks in their way. So I would like to remove those stumbling blocks,” she said.

And that’s what the state right now is planning to do.

“We’re making arrangements for the certifying exam to be taken in your own language,” said Kate Walsh, secretary of the Massachusetts Executive Office of Health and Human Services.

Walsh said there are a lot of newcomers in the state with clinical experience who could work as CNAs.

“They can start on this and get their family on a pathway to independence and resilience and also really fill a critical need,” Walsh said during a visit to the Berkshires in March.

The state plans to offer the test in Spanish, Chinese, Haitian Creole and English, starting July 1.

State Sen. Jo Comerford is trying to force similar changes through legislation.

Comerford's proposal would also direct the Department of Public Health to remove any question from the exam that is unlikely to be understood or that does not align with textbooks approved by the department.

All are steps — supporters say — to help solve a shortage in a key health care position across the state.

Copyright 2024 88.5 NEPM. To see more, visit

88.5 NEPM

.