Gwen Abele used to visit the former Walter E. Fernald State School with her disabled son. They would walk through the woods and visit the swimming pool and playground along the sprawling 200-acre property.

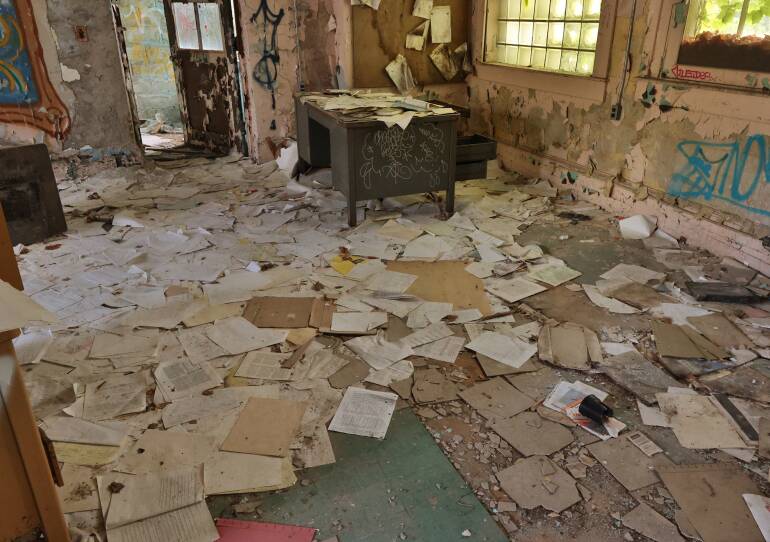

After the school closed, Abele said she grew concerned that the Fernald campus — home of the country’s first public institution of its kind to care for people with disabilities — became increasingly abandoned. Its dilapidated buildings were strewn with trash and splashed with graffiti.

Now, the future of the former Fernald school, which opened its doors in 1888, is the subject of a fierce debate among Waltham residents and those who once lived at the school.

Plans approved by the city’s Parks-Recreation Board in summer 2022 designate 120 acres — more than half of the land — to amusement and recreation, including a skating park, amphitheater, gardens and natural preservation.

Last month, construction began on a smaller, 16-acre plan that would establish “memorial and universal” park areas near Trapelo Road, as City Councilors described in a December meeting. That narrower plan includes a universally accessible playground, an electric train, a mini golf course and a spray park that would make it the largest disability-accessible park in New England, as Kim Hebert, the city’s director of recreation, explained in a committee meeting last November.

The City Council late last year approved a $9.5-million loan to finance the project.

But Abele says she and other Waltham residents are “enraged” with new plans to build a recreational park on part of the property.

“There’s no transparency as to what’s going on,” Abele said. “It’s just obscene to me ... for them to build something that’s for amusement on a sacred ground that should be memorialized and considered more of a contemplative place to respect what’s happened in the past.”

Prompted by complaints from residents, the City Council last month held a public input meeting about the Fernald land, where dozens of people addressed the council for nearly three hours.

Many attendees called for more transparency and opportunities for public input in future development plans, asking for a master plan detailing the city’s proposals for the entire property. Others were concerned the existing plans don’t fully serve the disabled community or memorialize the Fernald’s history.

A few residents expressed support for the recreational plan. One resident who spoke in front of the City Council said he supports expanding the city's “enviable, family-oriented recreational areas to all parts of the city” and is looking forward to bringing his grandson to the park.

Reggie Clark, who lived at the Fernald in the 1960s, said he wonders why the city never asked him or other former residents for their input. He wasn’t at last month’s meeting and said he didn’t receive enough notice to attend.

The 70-year-old man, who now lives in North Leominster, told GBH News he’d like to see a museum built on the site that documents the Fernald’s complicated past. The school is known for troubling medical experiments conducted by MIT and Harvard, where breakfast cereal was laced with radioactive iodine.

“They did not come to us and ask us what we want. Why would they put a recreational park?’’ asked Clark, who also serves on the state’s Special Commission on State Institutions. “What is that going to do for us?”

Councilor at Large Colleen Bradley-MacArthur told GBH News that she called for the meeting to give people the opportunity to weigh in on how the rest of the Fernald property should be used.

“I hope that this will give members of the design team and the Recreation Department a roadmap for what the community truly wants to see happen with this site,” Bradley-MacArthur said.

The property has been in the city’s hands for a decade. After the Fernald’s last resident left in 2014, the state sold the property to the city of Waltham for $3.7 million. Most of the property was bought with funds from the Community Preservation Act, which mandates part of the acreage be used for conservation, recreation, open space, affordable housing or historic preservation.

Alongside debate over the property’s future, the Boston Globe recently reported that State Police left decades' worth of confidential case files at the Fernald site. According to the article, State Police removed the evidence from the site by 2017, but it remains unclear why it was stored there to begin with.

Authorities are also under criticism after it was discovered that patient medical records were left sprawled on the campus. GBH News reported last week that the federal government is conducting a civil rights investigation into a patient privacy breach. At the same time, family members of former Fernald residents are facing ongoing struggles accessing their relatives’ records, an issue documented by GBH News.

Officials from the state’s Department of Developmental Services said “any materials” from accessible buildings were removed last month and are currently being stored at a state facility.

Alex Green, a researcher and disabilities expert at the Harvard Kennedy School, lives in Waltham and says that the current plans don’t reflect what the community wants — including preserving nature and documenting the Fernald’s history. He says the neglect of the Fernald property is “outrageous.”

“Some of the most disability-accessible buildings in the state could have been used for housing, they could have been used for community arts, they could have been used to really integrate the campus into the community with open space and with memorialization,” he said. “Those chances are gone now.”

Bryan Parcival, who was hired by the city in 2019 to document the campus, said he was “appalled” by its condition.

When Parcival visited in 2014, he said that most of the site’s 73 buildings were in good condition, with water and power still running. There was even a fully functioning hospital, he said.

By 2019, Parcival said most of the buildings were deteriorated or demolished by the city.

“If Waltham had had some vision, which at the time I thought they would, there would have been a lot of available housing,” Parcival said. “I have been appalled by the deterioration and the aggressive neglect and the obscene level of vandalism that has descended upon that property.”

About 25 buildings have been knocked down and the land restored to natural wetlands, said George Darcy, a former city councilor and member of a group of concerned residents called the People’s Fernald Working Group.

The broader plan for 120 acres of the property, approved two summers ago by the Parks-Recreation Board, is for “land only.” Building improvements will be in a “different project,” according to 2022 filings from the Parks-Recreation Board.

Questions from GBH News about the timeline and scope of the recreational project directed to Mayor Jeannette McCarthy’s office and the Parks-Recreation Board went unanswered.

Bradley-MacArthur says that there’s hope in the future planning process.

“There’s more acreage outside of just what the Recreation Department controls to implement things that were suggested,” she said about concerns expressed at last month's meeting. “I really hope that everyone that works on this project and touches this project keeps the disability community top of mind.”