A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket took off from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California Monday afternoon, carrying a satellite designed by scientists at Harvard University that’s designed to help in the fight against climate change.

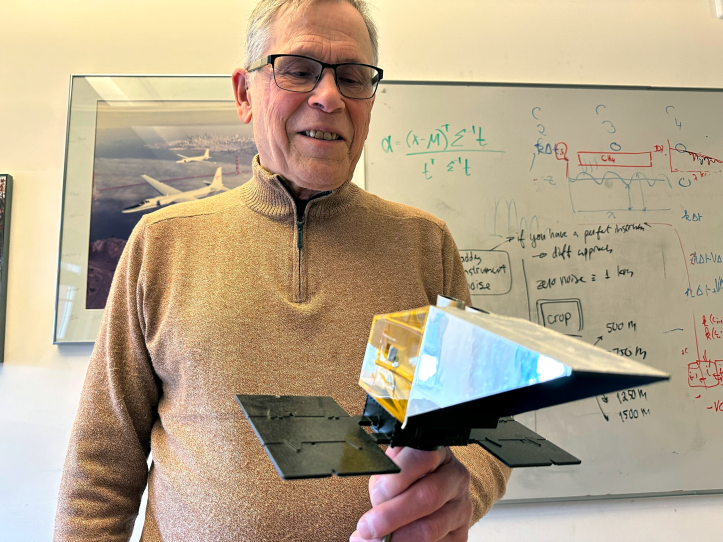

In his office at the Harvard University Center for the Environment recently, Steven Wofsy picked up a model of the satellite he and his team designed. It’s called MethaneSAT.

“These are the solar panels,” he pointed out, explaining how they would fold out from the sides, giving the satellite about a 30-foot wingspan. “It’s actually going to be quite a big bird.”

The satellite itself is about the size of a washing machine, he said.

Wofsy pointed to the bottom of the model, where the spectrometers stick out.

“The spectrometer is carefully designed so that it can measure the spectroscopic signature of methane in the atmosphere,” he explained.

Methane, a greenhouse gas 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide over its first 20 years in the atmosphere, is at the center of the satellite’s mission. MethaneSAT is tasked with creating a detailed global picture of where methane is being emitted from.

“Methane is responsible for currently about 30% of the warming we’re experiencing,” said chief scientist Steven Hamburg of the Environmental Defense Fund, which is picking up the $88 million cost to build and launch the satellite.

“If we can reduce the emissions of methane from human causes — human sources — we can rapidly reduce the rate of increase in the warming,” Hamburg said. “So, it’s an opportunity over the next couple of decades to slow things down.”

Those human causes include landfills and agriculture. But the main target of the satellite is detecting methane leaks from the oil and gas industry, Hamburg said.

“Some call it the low-hanging fruit. I like to call it fruit lying on the ground,” he said. “We can really reduce those emissions, and we can do it rapidly and see the benefits.”

This is not the only satellite currently in orbit that can detect methane, but Wofsy said it’s the only one that can measure it at this scale. Looking all over the globe, it can see both large-scale methane emissions and individual plumes of the gas from a single oil well or compressor station. He said they will share information about those leaks with oil and gas companies.

“Some companies don’t care about the methane they emit. Many companies do, especially those that are selling the natural gas,” Wofsy said.

But oil and gas companies often don’t know when and where they’re leaking methane, he said.

“Methane is not visible. And it’s not monitored,” he said. “Monitoring methane over all of the millions of wells and compressor stations and such is a tall order, and it’s not done.”

“Some call it the low-hanging fruit. I like to call it fruit lying on the ground.”Steven Hamburg, Environmental Defense Fund, on methane leaks from the oil and gas industry

MethaneSAT won't have the accuracy to catch individual leaky pipes in the streets around Boston, Wofsy said.

“But the sum total of those emissions, which raised the level of methane in the city as a whole, we should be able to see that,” he said. “And that's actually one of the things we designed the satellite to do.”

The goal is also for the data to be used by governments to regulate methane emissions. On Friday, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is scheduled to publish new methane regulations that will require states to write their own plans for cutting those emissions, and MethaneSAT could help states develop those plans, Wofsy said. Information the satellite gathers will also be publicly available.

“From what I’ve seen with some of the way people have used methane data already available from satellites, there’s going to be a lot of creativity out there,” he said. “There’s going to be people using these data, doing things with it that we never imagined, and I’m really eager to see what that turns out to be.”

Climate change can’t be stopped just by reducing methane emissions. But it can help slow the process, if we know where those emissions are coming from, Wofsy said.

“We can’t bend the curve just by going to a meeting and telling people that they have to emit less methane,” he said. “We have to have understanding about where it is. We have to have data about where the emissions are happening.”

With the successful launch of MethaneSAT, he said, we’re one step closer to having that crucial data.