Through the Superfund program, the federal government has for decades collected payment from big companies that create hazardous waste while doing business. It’s a pretty simple concept: The polluter pays.

This legislative session, some Vermont lawmakers and environmental advocates are pushing for the state to create a similar program to pay for climate damages in the Green Mountain State using money from big oil companies.

Climate change is bringing more supercharged storms to Vermont, and the costs are piling up . State officials estimate that July’s historic flooding will cost taxpayers north of $1 billion in property damages.

That price tag is just for one storm. A 2021 study from the University of Vermont estimated that climate-change-fueled flooding damages in the Lake Champlain basin alone could top $5 billion by the end of this century .

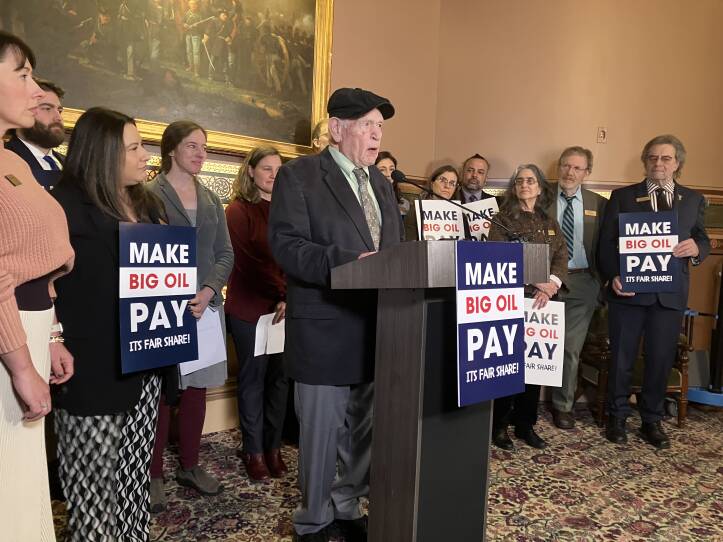

During a press conference at the Statehouse last week, environmental advocates and Democratic lawmakers from heavily affected districts said their constituents shouldn’t have to foot that bill.

“Let’s be clear. Vulnerable Vermonters, mom and pop businesses in small cities and towns, aren’t the cause of this damage,” said Sen. Anne Watson, a Democrat who represents Montpelier and Barre and is a lead sponsor of the Climate Superfund Act. “Big oil knew decades ago that their products would cause this damage. So it is only right that they pay a share of the cost to clean up this mess.”

Under the bill, S.259 , Vermont would mimic the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Superfund program , which makes big companies pay to clean up toxic waste they made while doing business. Since its launch in 1980, the program has been used to clean up catastrophic pollution at mines and old abandoned factories across the country.

Vermont’s bill would create a similar program, but for climate damages. Companies that produced more than 1 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent between 2000 and 2019 would have to pay a share of what climate change has cost Vermont, based on how much that company contributed to global emissions during the same period.

“It’s essentially taking that model that’s well established in the hazardous waste context and adapting that to the latest and most pressing environmental crisis we all face, which is climate change,” said Anthony Iarrapino, a lawyer and lobbyist for the environmental advocacy group Conservation Law Foundation.

U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders has introduced a similar bill at the federal level, though Iarrapino says it’s unlikely to get through Congress. At the state level, climate superfund bills have also been introduced in Maryland, New York and Massachusetts.

“It’s a good idea,” said Patrick Parenteau, Vermont Law School professor emeritus. “But like a lot of good ideas, it’s the execution and the implementation of a law like this that gets complicated.”

Parenteau used to litigate Superfund cases for the EPA’s New England office. He says the stickiest part of the federal Superfund program is actually getting big polluters to pay up and part with their money. Superfund cases tend to be big, complex legal battles that can take years to resolve in the courts.

Part of the challenge, Parenteau says, will be building an airtight accounting of the damages caused to Vermont by the global burning of fossil fuels and the investments needed to adapt to a warming climate. It’s a task the bill leaves to the state treasurer to complete by 2025.

New York State has already tallied this figure, estimating that adapting to climate change could cost the state more than $150 billion by 2050. The bill’s proponents here say Vermont could borrow from that work, which leans on a field of science called extreme event attribution, which can help determine how much more powerful a storm was because of climate change.

For many of the extreme weather events Vermont is likely to see more of, scientists can do this work with growing accuracy.

Vermont Treasurer Mike Pieciak says he’s excited about the task.

“At the end of the day, Vermont is going to have a lot of money due because of climate change, and the question is kind of: 'Who is going to pay for that?'” Pieciak said.

He says it shouldn’t be all on Vermonters to foot the bill, and he thinks his office can build a list of damages that’s airtight and could withstand litigation.

Parenteau, with Vermont Law, says they’ll have to.

“Companies aren’t just going to cave in,” he said. “They’re going to fight like hell and say, ‘We’re not liable, you can’t make us liable. This is a global problem. It requires a global solution. You could sue us and put us out of business and it wouldn’t fix the problem.’”

"Companies aren’t just going to cave in. They’re going to fight like hell and say ‘We’re not liable, you can’t make us liable.'"Patrick Parenteau, professor of law emeritus at Vermont Law and Graduate School

In an emailed statement, Michael Gaimo, Northeast region director for the American Petroleum Institute — which represents U.S. oil and natural gas companies — says the Climate Superfund Act takes the wrong approach.

"This proposal is likely unconstitutional and represents nothing more than a punitive new tax on American energy that would only stall the innovative progress underway to accelerate low-carbon solutions while delivering the energy communities need," he says.

Parenteau says the state will also have to make sure it can prove that what it’s spending money from the fund on is actually making Vermont more resilient to climate change — something big companies often sue over in Superfund cases.

The bill tasks the Agency of Natural Resources with creating a master plan for how to spend the funds on projects ranging from improving roads and bridges to weatherizing homes and helping communities repair damages to businesses after extreme weather events.

And while lawyers find this path promising, it isn’t the only way Vermont is using the legal system to try to get big oil companies to pay up.

In 2021, Vermont’s Attorney General sued Exxon, Shell, Sunoco and CITGO under the Consumer Protection Act. The lawsuit alleges the companies knew their products were contributing to global warming for decades, and lied to the public about it — even launching targeted disinformation campaigns.

The suit calls for the companies to stop greenwashing — but it also seeks financial damages.

“The civil penalties associated with the Consumer Protection Act are up to $10,000 per violation,” says Vermont Attorney General Charity Clark. “So that’s per consumer, per time you lied. So magnify that over the decades: It’s a lot of money.”

Clark’s office just filed their last documents in the case earlier this month. Right now it’s held up in the federal court system, but Clark says the consumer protection approach is a winner, because the receipts are pretty clear.

Iarrapino and Parenteau say the superfund approach should be even more straightforward, from a legal perspective, since it relies on the principle of “strict liability,” and doesn’t require proof of willful wrongdoing.

But again, Parenteau says, if lawmakers pursue this approach, Vermont would be wise to staff up on lawyers for the fight ahead.

Iarrapino says he doesn’t disagree, but that what matters is the strength of the legal argument itself.

"It’s true that there is a history of legal resistance on the part of polluters [to paying],” he said. “But there’s also an equally compelling history of the states and federal government seeking to hold those polluters accountable and prevailing in court.”

The Climate Superfund Act has more than 100 sponsors in the Legislature, including a supermajority in the Senate, which has tended to be more conservative than the House on climate issues this biennium.

Sen. Dick Sears, a Democrat from Bennington County who chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee, where the bill is now, says he’s been talking to small businesses in his district that still haven’t received federal aid from the July floods, who could really use help getting back on their feet.

He says a decade ago, he might not have supported legislation like this, but he said he changed his mind after he saw how the plastics manufacturer St. Gobain was made to pay for carbon filters in homes where drinking water was found to be contaminated with toxic PFOA chemicals as well as medical monitoring for residents affected in his district.

“I don’t know where else the victim pays,” he says. “I’ve dealt with criminal justice laws on judiciary for years, and everywhere, the victim is not the one that’s responsible to pay, it’s the offender. And here, for some reason, with these major companies, they aren’t required to pay the victim.”

Gov. Phil Scott has yet to weigh in on the proposal, but even if he vetoes the bill, it appears likely based on the number of sponsors alone that lawmakers could mount an override.

Have questions, comments or tips? Send us a message or contact reporter Abagael Giles.

Copyright 2024 Vermont Public. To see more, visit Vermont Public .