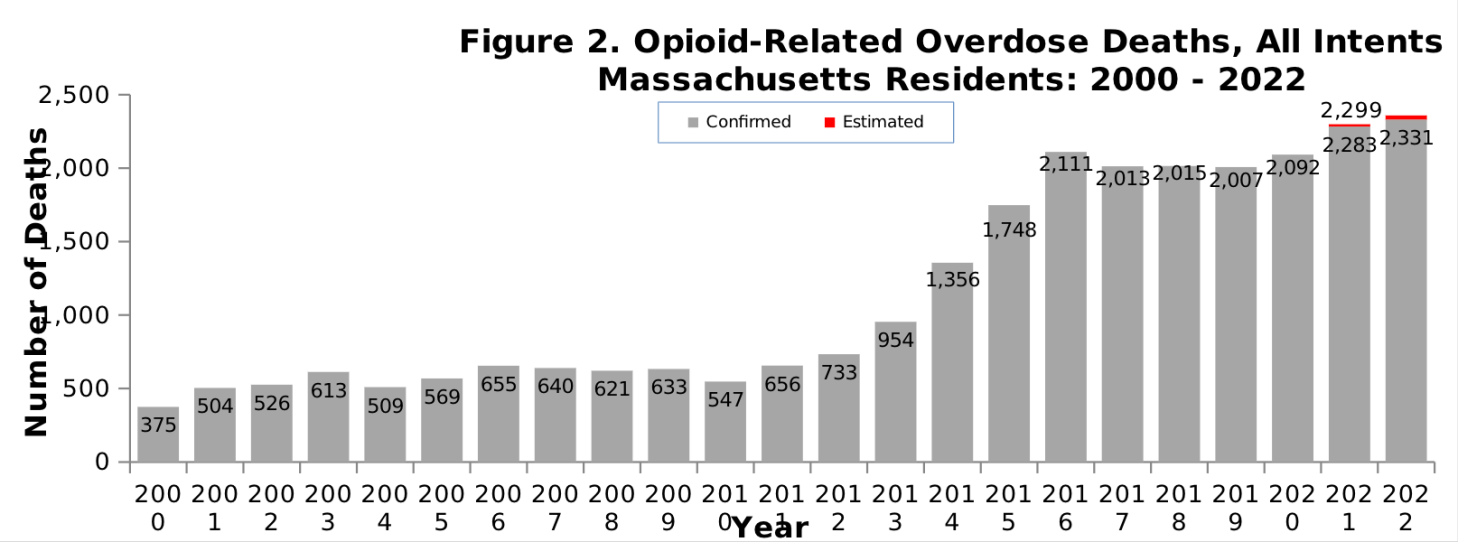

Overdose deaths in Massachusetts continue at discouragingly high levels as the opioid epidemic churns on, and the drug supply in the state is “poisoned,” according to officials at the state Department of Public Health.

“We have a toxic drug supply that does not just affect people who have an opiate use disorder,” said Deirdre Calvert, Director of DPH’s Bureau of Substance Addiction Services. “We have found fentanyl and xylazine in methamphetamine, cocaine and other substances.”

Xylazine, also known as “tranq,” is a powerful sedative used by veterinarians. Fentanyl is an extremely strong opioid, which makes overdoses much more likely to be fatal; it was found to be involved in 93% of overdose deaths in the first quarter of this year, according to the latest reports released Wednesday by DPH. The report showed 1,718 confirmed and estimated deaths for the first nine months of this year.

“I think the take home is that when looking at opioid overdose deaths in the state of Massachusetts, things are really not getting much better,” said Dr. Andrew Kolodny, the medical director for the Opioid Policy Research Collaborative at Brandeis University, “that the interventions that the state is trying right now are not having much of an impact on reducing overdose deaths.”

Kolodny pointed out that some findings that were not part of the latest release from DPH did show “some light at the end of the tunnel.”

“We have seen in Massachusetts a very significant decline in neonatal abstinence syndrome,” Kolodny said. “The number of infants born opioid dependent has been coming down steadily — probably in response to more cautious prescribing of opioids.”

Included in Wednesday’s release was a feasibility study on opening overdose prevention centers in the state , where people could use street drugs under supervision.

DPH Commissioner Dr. Robbie Goldstein said such centers had strong track records of preventing overdose deaths and even helping people enter treatment, but he also said there would have to be buy-in at the municipal level.

“The idea of putting an overdose prevention center where the community may not want it is not likely to result in a meaningful decrease in opioid related overdose deaths,” Goldstein said, “because people are unlikely to go to that place that they're feeling in a hostile environment.”

Goldstein also underscored that there were liability concerns for municipalities, and that the state legislature and governor would have to exempt them from state criminal and civil prosecution. Even then, overdose prevention centers would be technically illegal under federal law. One center has been operating in New York City since 2021 without either state or federal authorization.

Kolodny said opening overdose prevention centers could have a positive effect in some parts of the state.

“In urban areas, where the problem is still getting worse, it makes sense,” said Kolodny. “In places where you have homeless injection drug users, having a place where they can inject and potentially be rescued should they overdose, or even linked to treatment as an intervention, that makes sense.”

But Kolodny cautioned that, with so many overdose deaths occurring in rural and suburban areas, OPC’s would not necessarily have the needed impact in all regions of the state.

“People are probably not going to commute into town multiple times a day to inject,” Kolodny said. “And so for the suburban and rural areas, we really need other interventions.”

Kolodny said offering wider access to high-quality opioid addiction treatment would be the most effective intervention to reduce the large number of overdose deaths in Massachusetts.

“People who are opioid-addicted wake up in the morning already feeling sick," said Kolodny. “Until we get to a point where treatment is far easier to access than fentanyl or a bag of dope. We're going to see high rates of overdose deaths; the treatment has to be essentially free.”