Paris Alston: This is GBH's Morning Edition. Although it may seem enormous, Planet Earth is just a small part of the Milky Way galaxy, which is just one of the billions of galaxies in the entire universe. But that wasn't always a known concept.

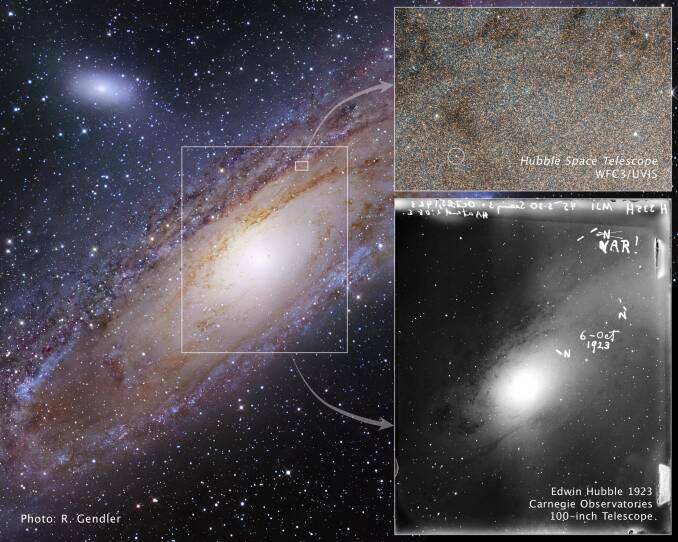

Jeremy Siegel: Today is the 100th anniversary of when the U.S. astronomer Edwin Hubble, who the Hubble Space Telescope is named after, took a photo of the first star in the Andromeda Galaxy. It marked a turning point in the space world that led to a major discovery: That other galaxies exist. Joining us to talk about this is Marcia Bartuziak, an author, journalist and professor of practice emeritus at MIT who's been covering the fields of astronomy and physics for decades. Good morning, Marcia.

Marcia Bartuziak: Good morning. It's so nice to be here.

Alston: So this is a monumental anniversary here. But Marcia, you were telling us before we came on air here that it's not as big as one might think for some folks in astronomy community.

Bartuziak: This is the 100th anniversary of the moment where we are discovering the modern universe. And it's always surprised me that it's not as well-known as, say, Darwin discovering evolution or Galileo discovering the moons of Jupiter. It's always remained a little in the background, and it's always been a mystery to me.

Siegel: So you are working to bring that to the foreground. You are the author of a book that is all about the story of what exactly happened 100 years ago. You have your book here with us. Tell us about that day.

Bartuziak: I will read from the book: 'On that moment, Oct. 4, 1923. The scene was poor, but it was good enough, just barely, to stalk some celestial quarry that autumn evening. As the giant scope swung around, there was a whine, a series of loud clicks, and then a final clang as the instrument was secured into place. He then maneuvered the telescope just a fraction of a degree to photograph M31, the famous Andromeda Nebula, the target of choice in the island universe debate.' And that night he saw a star that he hadn't seen before in the Nebula. He had been scanning the sky for years, so he was very familiar. And the next night he confirmed it. And then he took those photographs back to his office, and he compared them with other photographs of Andromeda that had been taken over the years. And he discovered that one was a variable star. That was his distance indicator. There was speculation that there were other galaxies in the universe, but it was all circumstantial evidence. What Hubble did was he had a direct measuring tape out to that star, and he was able to determine that it was more than a million light years away, far beyond the borders of the Milky Way. And that was the moment that we knew that the universe was far bigger, far more complex than they had ever imagined before.

Alston: Oh, the day we found the universe, as you've titled the book so fittingly. So, Marcia, what impact did that discovery have on the world of astronomy going forward?

Bartuziak: Terrifically. Before this, astronomy was relegated to studying the stars in the Milky Way, the planets. It was a small little community, and Hubble expanded that terrifically. It's as if we had been living on one square yard of dirt on the earth and suddenly realizing, Oh my God, there are mountains and rivers and lakes and oceans and continents. It expanded the field of astronomy tremendously. Hubble founded the field of modern cosmology. So instead of just stars and planets, we now had a far vaster, trillions of times bigger than previously thought.

Siegel: It's amazing to think back on how this moment 100 years ago changed everything and expanded our understanding, but also our curiosity about the universe. I mean, from something being what we think it is to going to trillions of times the size, it leads to so many open questions, many of which are still open in the cosmology community, right?

Bartuziak: Exactly. It opened up the questions of our origin because later, of course, a few years later, Hubble came up with the observational evidence that the universe was expanding. And of course, then we started thinking, well, if it's expanding, what if we looked back in time and thought about all those galaxies coming together? And it then brought up the idea of the Big Bang, that there was an origin to our creation that had never been thought of before.

Alston: And also, Marcia, today, a little bit before this 100-year anniversary, we got those images from the James Webb telescope that gave us the most expansive view ever of the universe as we do know it today. So given how far we have come since the Hubble was invented, why should we be getting excited about this anniversary?

Bartuziak: Oh, because it's a reminder that every time you have a new telescope and Hubble was using then the biggest telescope in the world, the 100-inch telescope at Mount Wilson, it shows that with each new telescope, new mysteries arise and have to be solved. New technology leads to new questions.

Siegel: Marcia Bartuziak, author, journalist, professor of the practice emeritus at MIT, thank you so much for joining us on this 100th anniversary of this amazing moment in science. You have us thinking about like, what's going to be the next moment like this that sets off the next century of research? Thank you so much for piquing our fascination this morning.

Bartuziak: I enjoyed being with you very much.

Alston: You're listening to GBH News.

On Oct. 4, 1923, astronomer Edwin Hubble trained his telescope onto the sky and snapped a photo of a speck of light within the cloudy M31, also known as the Andromeda galaxy.

Hubble initially thought that speck of light was a nova. But over the next couple days, he observed it had a predictable pattern of brightening and fading, indicating it was actually a variable star. And from that, he was able to determine how far away it was from Earth.

It marked a turning point in the space world that led to a major discovery: Other galaxies exist.

“It's as if we had been living on one square yard of dirt on the Earth and suddenly realizing, 'Oh my God, there are mountains and rivers and lakes and oceans and continents,'” said Marcia Bartuziak, an author, journalist and professor of practice emeritus at MIT.

The moment changed modern cosmology, said Bartuziak, whose 2009 book “The Day We Found the Universe” tells the story of Hubble’s discovery.

“This is the 100th anniversary of the moment where we are discovering the modern universe,” she said. “And it's always surprised me that it's not as well known as, say, Darwin discovering evolution or Galileo discovering the moons of Jupiter. It's always remained a little in the background, and it's always been a mystery to me.”

The images also spawned new questions: Could images of space hold clues to the origins of the universe?

“A few years later, Hubble came up with the observational evidence that the universe was expanding,” she said. “Well, if it's expanding, what if we looked back in time and thought about all those galaxies coming together? And it then brought up the idea of the Big Bang, that there was an origin to our creation that had never been thought of before.”

Images from the James Webb Space Telescope released last year, which show details of the universe never before seen on Earth, underscore the thrill of discovery.

“With each new telescope, new mysteries arise and have to be solved,” she said. “New technology leads to new questions.”