On a recent Tuesday morning in downtown Lowell, Manuel Eusebio climbs the stairs to a local nonprofit called Thrive Communities, where a half dozen other formerly incarcerated men and women are all looking for help to restart their lives.

Paroled just four months ago after spending much of his last 15 years cycling in and out of Massachusetts’ prisons and jails, this middle-aged man in a black golf shirt is determined not to land back behind bars again.

Eusebio knows how hard it is to get help from the state that incarcerated and then released him — and how things can go terribly wrong.

“I didn’t have recovery support. I couldn’t find a job and [had] nowhere to go,” he said about his last bouts outside prison walls. “I just resorted to what I knew would help me to survive.”

It brought Eusebio back to prison multiple times. Reentry is a challenge for the thousands of men and women convicted of crimes who are released from prisons and jails into Massachusetts communities each year — more than 50,000 such releases since 2017, according to state data. About a third of former prisoners end up back behind bars within three years.

Their needs are immense — seeking housing, employment, mental health treatment and a feeling of belonging after the trauma and stigma of incarceration. And they are much more likely to become homeless , die of a drug overdose , or die of suicide than the general population, studies show.

“I couldn’t find a job and [had] nowhere to go. I just resorted to what I knew would help me to survive.”Manuel Eusebio, on his last bouts outside prison walls

Over the past several decades, Republican and Democratic administrations in Massachusetts have rolled out big announcements of new programs to help people like Eusebio succeed after their time behind bars. But there is a huge gap between what the state’s reentry programs aim to provide and what services returning citizens can actually access, the GBH News Center for Investigative Reporting has found.

Dozens of returning citizens told GBH News that they came out of prisons and jails with little or no organized support from the state, no resources to help them succeed and no job leads.

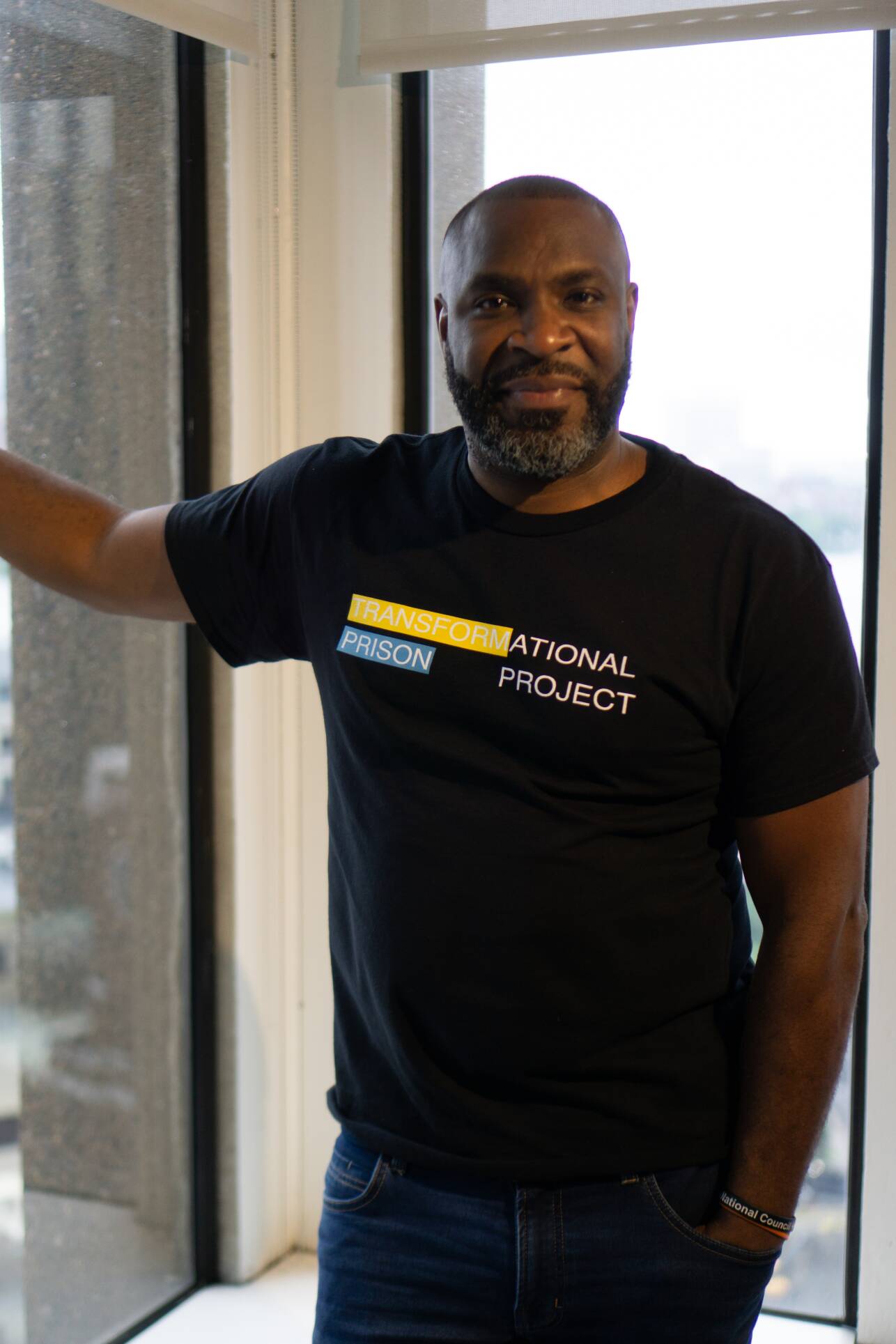

Armand Coleman, executive director of the Transformational Prison Project in Cambridge, says when he was paroled in 2019, he realized how few resources were available.

“They have a paper they give you that’s been circulating around the prisons for decades of resources they’re going to give you when you come home. The only one that actually showed me any support was the Department of Transitional Assistance,” he said. “Every other thing on it was 100% fake or didn’t exist.”

For the government-run services that do exist, advocates like Carole Cafferty, a former jail superintendent and co-director of The Educational Justice Institute at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, say they can be hard to find — and often, hard to be trusted.

“If you’re not tied in, or you don’t know who the champions are, you really are sometimes lost,” Cafferty said. “It really has to be a group of people working together with parole — if they are on parole — or with the reentry at the correctional facility and with a community health center.”

And the stakes for supporting successful reentry are high — not just for people leaving jails and prisons, says Kamal Oliver, who coordinates reentry services at the Louis Brown Peace Institute in Dorchester.

“If these guys are coming home from incarceration and they don’t have anyone to turn to, they don’t have any resources available to them and they feel like they’re alone and they feel like they don’t have a shot, guess what they’re going to do? They’re going to cause havoc in the community,” Oliver said.

Department of Correction officials told GBH News that Massachusetts is a “national leader” in its efforts to reduce recidivism, including expanded programs to provide education, job training and mentorship.

Over time, the state’s recidivism rate has slowly trended down. About 35% of state prisoners released in 2007 committed new crimes and returned to prison within three years of release, according to state data . For prisoners released in 2016, data shows that number dropped to 26%. And the real number of people returning to prison is higher if it includes parolees reincarcerated for violating technical terms of their release, like drinking alcohol or being unable to maintain employment. That puts Massachusetts’ recidivism rate slightly below the national average, according to Department of Justice data .

But even state officials like Vincent Lorenti, who heads the Office of Community Corrections in the Massachusetts Probation Department, say more needs to be done. He told GBH News that the state has been making a “fervent effort” to increase services for formerly incarcerated people over the last several years.

“There are still a lot of gaps,” he said, “but I definitely think there’s a lot of activity going on.”

What the state does, and doesn’t, provide

In the new Massachusetts budget, signed this month, state agencies set aside just over $50 million for reentry programs, including housing, workforce training, addiction and mental health treatment, according to data from the Legislature. That investment is less than 4% of what taxpayers are spending to incarcerate nearly 12,000 men and women in Massachusetts’ county-run jails and state prisons.

State agencies and county sheriffs have been grappling with reentry issues for decades with mixed results.

For example, the state operates eight Regional Reentry Centers, created almost two decades ago under former Gov. Mitt Romney as the answer to recidivism. Between 400 and 1,000 returning citizens head there each year for assistance in housing, jobs, health care referrals and other needs, according to parole reports. But advocates say the centers, housed inside secure regional parole offices, are largely not trusted because people are afraid of being sent back to prison.

“I don’t want to say people are intimidated, but it isn’t, like, a warm, fuzzy place that you can turn to when you’re in need,” said Joseph Moore, a therapist with the Second Chance Justice Program in Brockton who has counseled people coming out of prisons and jails for 27 years.

A 2020 state audit found that the Department of Correction was failing to keep track of reentry services that were supposed to be provided to departing inmates.

State officials told auditors that “some [DOC] employees did not have appropriate reentry training,” among other issues. Since then, state officials say they have improved the system, including new training for staff and improved monitoring of former prisoners’ outcomes.

“It isn’t, like, a warm, fuzzy place that you can turn to when you’re in need.”Joseph Moore, a therapist with the Second Chance Justice Program in Brockton, on the state’s Regional Reentry Centers

In many cases, programs go on with little evidence of success. In 2014, Massachusetts officials trumpeted the creation of one of the nation’s first “Pay for Success” programs that had private venture capital firms putting up millions of dollars to fund a recidivism-reduction program.

The Chelsea-based, youth-focused nonprofit Roca, Inc, was hired to support and train about 1,000 young offenders with employment programming and life skills — and the state pledged to pay $28 million if the program proved it had “positive societal outcomes and savings for the commonwealth.”

Ten years later, the state has paid out $11.8 million but still has not reported whether the program was successful. Roca leaders told GBH News last week that the program “presented some significant challenges” and is “vastly different” from how it was originally planned.

“We are working collaboratively with the Commonwealth and other partners on the final report for this project and will defer further comment on it until the report is released,” Roca spokesperson David Guarino said.

Problems with reentry are compounded by gaps in the education system inside prison walls. An investigation published in June by GBH News found thousands of prisoners awaiting education that could help them succeed once they are released. State education regulators found DOC’s career-preparation program showed “limited evidence” of success during an onsite review in 2021, according to an internal report obtained by GBH News.

The report said inspectors found the career office failed to track where former inmates ended up and whether they were engaged with workforce partners such as MassHire, a state agency that connects people with jobs.

Prisoners “displayed no awareness ... of post-release employment options,” the report said. They also had, “no one to talk with inside the program about their future career or business plans.”

Building trust

For Eusebio, much of his support is now coming from a grassroots organization.

Thrive is one of dozens of nonprofits across the state trying to fill gaps in a reentry system with many government-funded programs that don’t always coordinate with each other or appeal to people distrustful of those with authority.

Thrive stresses community. Eusebio said getting invited to a cookout hosted by the nonprofit earlier in the summer was a turning point where he bonded with his coach, also a formerly incarcerated man.

“I didn’t know this man from a hole in the wall. For him to just come and be like, ‘Yo, come on, you can do this,’ and be supportive and give me positive advice, that means more than all the money in the world right now,” Eusebio said.

Building trust is key, Cafferty said. She says it’s hard for people to bring their problems or concerns to their parole or probation officer. A better approach, she and others believe, would offer wraparound services run by organizations unaffiliated with — but supported by — the justice system.

“If you have the power to surrender somebody and send them back to a correctional facility — if they relapse, they misstep — it’s kind of hard to build a strong, trusting relationship with that person,” Cafferty said. “It’s an independent person who they believe they can rely upon and trust upon release.”

“God, I can name like 12 organizations that are led by directly affected people. And none of us are getting the resources that we need to operate.”Leslie Credle, Justice 4 Housing

But Massachusetts is moving the other direction. The state has increased the rate of people being released on probation or parole. In 2022, four-fifths of the people released from state prisons were under community supervision — up from 60% in 2017, according to DOC records .

To Lorenti at the State Probation Service, the increase in supervision is a benefit, similar to seeing a health provider more frequently. The agency is ramping up 18 Community Justice Support Centers to meet the growing caseload of people being supervised or voluntarily seeking help, he said.

Lorenti said he understands why formerly incarcerated people might want to avoid working with someone connected to the probation department. But, he said, “the reality is we would have a bigger impact if we were able to engage with them, by building trust.”

In February, for the first time, Boston’s Office of Returning Citizens issued $1 million in grants to community-based organizations — many run by formerly incarcerated people — to boost their reentry programs.

But even that process can prove challenging because many organizations lack the infrastructure to manage reporting requirements of a government grant.

David Mayo, head of Boston’s Office of Returning Citizens, said his agency is looking at ways to improve systems and help community-based groups participate in city grants.

“What we’re learning is we have to spend more time educating and getting them to the table to understand what it means to receive a grant [and] what it means to apply for a grant,” he said.

Housing: The first and highest hurdle

Housing remains a huge barrier to successful reentry, according to dozens of interviews for this series over the past year.

And without stable housing, “you can’t get a job. You can’t focus on mental health, you can’t focus on substance use,” said Leslie Credle, who directs Justice 4 Housing, a Boston nonprofit dedicated to reentry housing.

A 2015 Harvard University study found that, six months out of prison, 35% of returning citizens were staying in temporary or “marginal” housing like a sober home. It grew to 43% after a year.

A person returning from a prison term may no longer be welcome in a family member’s home, or a family member’s lease may prevent a person with a felony conviction from living there. Going back home may also bring risks of recidivism because it returns a person to the surroundings that fostered their original criminal activity.

But their criminal record may make it hard to rent anywhere else, particularly in high-cost cities in Massachusetts.

For many, that leaves sober homes as the first option — even for many people who have no addiction problem.

“I’m currently staying at a sober house even though I don’t have an addiction issue,” said Jose Bueno, who spent 16 years in prison, and has been out for a little over a year. “You got to play the game,” he said in June. “Tell them what they want to hear, you know?” And staying in a sober home limits the hours he can work because he has to participate in recovery programming.

This month, Bueno was told his eligibility for the sober home was expiring and he has been scrambling to find new housing.

At Justice 4 Housing, Credle said state agencies and prison staff refer people to her for help with housing and other services.

“We get referrals from probation. We get referrals from jails,” said Credle, who has also served time behind bars. “From the case managers inside jails, like, ‘Hey, I got this person coming out.’ You know, do we turn him down? No.”

But state agencies don’t provide any funding to help her nonprofit pay for that assistance.

“Formerly incarcerated people — we are leading right now. We’re leading in reentry.” she said “There’s — God, I can name like 12 organizations that are led by directly affected people. And none of us are getting the resources that we need to operate. It has not trickled down.”

New state initiatives

Early this year, Massachusetts officials unveiled a new initiative to make it easier for people returning from state prisons to obtain a state-issued ID — considered a critical first step for successful reentry.

Under the new agreement, the Registry of Motor Vehicles and the Department of Correction pledged to coordinate information about inmates coming up for release so they can be issued a state ID by the time they leave prison. For years, people have been released from prison without a state ID, which can make finding housing or employment nearly impossible.

The Department of Correction also launched a new program in 2021 called Credible Messengers, pairing up prisoners soon to be released with mentors who were formerly incarcerated or who have close family members who were in the penal system.

Sharlene Blake, who’s married to a man on lifetime parole, works as a Credible Messenger based in Worcester.

“What I like to offer to those people that you meet on the inside is just so much support,” Blake said at a roundtable last March at the DOC’s pre-release center in Roslindale. “Building a strong enough relationship that they trust you, that they will participate in their own reentry.”

Eusebio is one of Blake’s clients. He said he signed up with the program a few months before being granted parole, and he credits her with helping him in ways that DOC staff never did. Blake met him almost every two weeks for two months, he said, and helped him find housing in Tewksbury.

“The DOC lady was just trying to set me up for failure. And that’s when I saw Sharlene,” he said. “She was like, ‘Don’t worry about it. I got you. I’m going to find you a place to go.’ ... I’m so grateful for her.”

Currently there are only five Credible Messenger mentors, each handling caseloads of about 50 people. But DOC officials say they see the benefits and are spending an additional $125,000 to hire two more mentors with a goal of reaching about 400 people this fiscal year — still a fraction of the total population of formerly incarcerated people.

Back in Lowell, Eusebio is focused on landing a job and finding secure housing.

His coach at Thrive, Sing Thanousith, is helping.

“I didn’t even know how to read an email, and he showed me,” said Eusebio. “They helped me get a license, my first ID, my insurance.”

But challenges are overwhelming. He said his brother recently died of an overdose. He’s been sleeping in his truck after complications at his sober home. He’s applying for jobs but says he’s been denied employment, even from landscaping companies, because of his criminal record.

He desperately wants to stay out of prison.

“I just need somebody to give me a chance so I can earn my place in society as a citizen and do the right thing,” he said.

Life After Prison is the latest investigative series from GBH News’ Center for Investigative Reporting on what people face when they return from prison. Read the first installment here.