At the Springfield Museums in western Massachusetts, the most recent exhibit connected to an aspect of the region’s Native American culture is on display at the Wood Museum of Springfield History .

Several Indigenous educators and scholars from around Massachusetts and Connecticut advised the museum on how to craft " We Have a Story to Tell: Stories, Maps and Relationship to Place ."

The display challenges visitors to think about how white people and Native Americans — both in the Colonial era and now — define land use and land ownership.

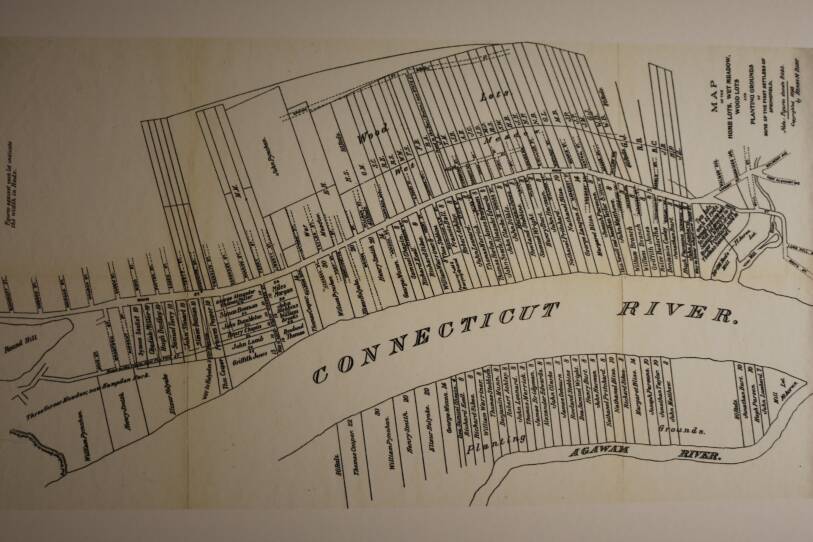

On one side of the room are display cases and wall hangings of 17th century maps and land deeds from around western Massachusetts, long ago drawn up by English Colonists.

On the other side of the room, a video plays on a loop, projected on a wall. It features

Larry Spotted Crow Mann

, an advisor on the exhibit — and among a group of Native Americans the museum contracts with for guidance curating exhibits on Native Americans.

Mann is a citizen of the Nipmuc Tribe of Massachusetts, and the founder of the

Ohketeau Cultural Center

in Ashfield.

In the video, Mann and Andre Strongbearheart Gaines tell viewers how the Nipmuc and other tribes thrived around central and western Massachusetts, and how and where many now live.

Mann speaks about how ancestral Indigenous peoples marked the land, not necessarily through paper maps but through stories and bent trees.

“As saplings, they would curve in certain ways and [be] taken care of — where they could point to water or point to certain things that people need,” Mann explains in the video.

Mann worked closely on the video and on “We Have a Story to Tell” with Cat White, a museum exhibit technician and — on this project — a guest curator.

White said she received a sort of “vague” grant last year to create anything related to the area’s indigenous history. She proceeded to dig through the Springfield Museums’ archives and came upon several Colonial-era documents showing what is now western Massachusetts.

It led her to question the maps, she said, designed in the Colonial era and generally by white men.

“You know, me, as a white person of European descent and American descent, I have an idea of what a map is,” White said. “A piece of paper with boundary markers, you know, names.”

Among the artifacts was a land deed that describes the transfer of a large parcel in Deerfield, near what is now called Mount Sugarloaf. Indigenous peoples called it Ktsi Amiskw or the Great Beaver.

The land was signed over by a Pocumtuck woman named Mashalisk to pay off her family’s debt. Historians say the exchange erased what they owed for 10 beavers, two coats and some other items. The recipient was John Pynchon , the son of William Pynchon — one of the founders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and considered the founder of Springfield.

In the exhibit's video, White explains how Colonial legal systems, debt and mapping were central to European settlement — and how colonists used these documents to take Indigenous lands, as did the U.S. government.

“We Have a Story to Tell” is the museum’s most recent show about Indigenous peoples. Last year the museum featured a photo and essay exhibit curated by Aprell May, who grew up in Springfield and is a reporter at The Republican newspaper.

The show was called “We’re Still Here.” It was apparently a stumble for the museum, which has publicly committed to creating more vibrant exhibits about the area’s Indigenous peoples. The museums’ Indigenous advisors asked the museum to take the exhibit down — and they did.

The group told the museum that May shouldn't be representing Indigenous peoples in the Springfield Museums because she isn’t claimed by a tribe. May is a descendant of the Mohawks of the Iroquois confederacy.

Larry Spotted Crow Mann was among the advisors objecting to May’s exhibit, but has declined to talk about what happened last year. During an interview about the new exhibit, Mann said he didn’t want to talk about May’s show.

“I'd rather not talk about this," Mann said. "I’m here to talk about my work and Cat’s work, and my involvement."

Mann and his brothers have been curating or advising the museum on its Native American exhibits for a couple of decades.

“As local tribal people, we've always been willing and available to help them get the story right. And, you know, there's there's been a lot of work done. There's still a lot of work to do,” Mann said.

Mann was born in Springfield. He’s a writer, an artist and a Nipmuc tribal historian. He said as a kid he came to the museum for school field trips, and the Native American exhibits were a bleak experience.

“The so-called Indian exhibit was very bland and short and [it was] the Neolithic period or the paleo-Indians and so on. And that's pretty much all you got,” Mann said.

That exhibit is a diorama in Native American Hall, in the Springfield Science Museum. It depicts three life-size Indigenous people gathering food and making tools, with an accompanying soundtrack describing their daily activities.

The exhibit was first built in the 1940s and Mann said it’s the type of display that’s long misrepresented Native Americans and implies they’re no longer in existence.

During his recent work for the Springfield Museums, Mann said he, curator Cat White and others discussed this.

“We talked about … the large, the Plymouth-Rock-stone kind of thing there, getting that out of there,” Mann said, chuckling, “and, of course, what would that take to get that out of there?”

Museum officials last year said it was a priority to remove the Native American figures. As of now, they're still there. A spokesperson did not have a timeline for its removal.

Nina Sanders , a curator and artist who has consulted at museums around the country, including the Smithsonian and the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, said when she works with museum directors and boards, she tells them they have the agency to fix problematic exhibits.

“One of the things that I say right off the bat is, ‘No, it doesn't, it doesn't take that long,’” Sanders said.

Sanders, who is Crow and grew up and lives on the reservation in South Central Montana , said among the challenges museums have making better exhibits about Native Americans — there are few Indigenous curators in the U.S.

"If every curator was Indigenous, and they were controlling the narrative, what does that do to society?” Sanders said. “I think it would be great!”

Like the Colonial maps on display at the Springfield Museums — created centuries ago by white people — Sanders said that same issue applies overall to how museums tell stories.

“All of these different sort of belief systems essentially tie back into land ownership,” Sanders said. "It ties back into who owns what and who controls the narrative.”

To curate “We Have a Story to Tell” at the Springfield Museums, Mann said there was a lot of back-and-forth with the museum — and there were some bumps in the road, though Mann wouldn't elaborate. He said he's satisfied with the display.

“We're literally undoing centuries of misrepresentation. This is just the beginning,” Mann said.

People who come to see Mann’s video and the maps at the history museum have to first pass through much of a large exhibit displaying memorabilia and bikes from the Indian Motorcycle Company, once manufactured in Springfield.

A few posted signs in that exhibit acknowledge the company’s branding was disrespectful and fails to represent Indigenous peoples.

Past the motorcycle exhibit, tucked in a gallery off a hallway, is “We Have a Story to Tell.” It's on display until Sept. 3.

This story originally appeared on New England Public Media . It is republished on GBH News through partnership with the New England News Collaborative.

Disclosure: Springfield Museums is a financial supporter of New England Public Media. Our newsroom operates independently of the station’s fundraising department.