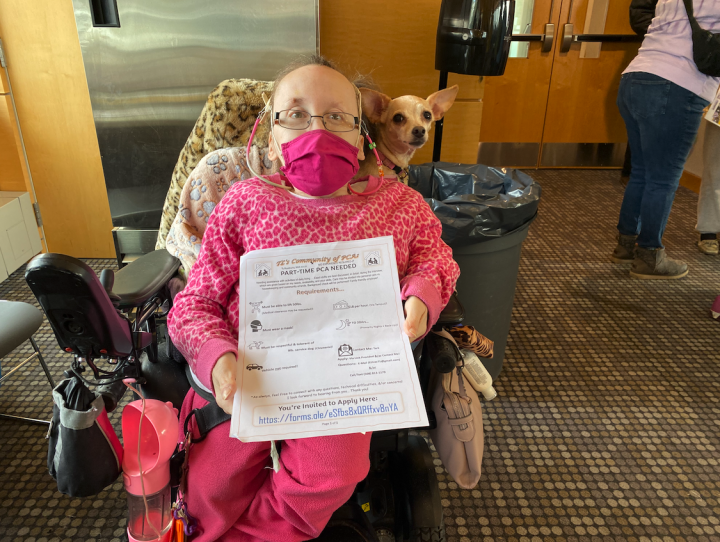

At the end of April, Tara Lynn Southard arrived at the Mattapan branch of the Boston Public Library on a mission. She had a stack of flyers in her hands. “Part-time PCA needed” they read, with a list of requirements: must wear a mask; be respectful of service dogs; able to work up to 20 hours, mostly at night; vehicle not required.

Southard, who uses a wheelchair and lives on her own on the Jamaica Plain-Roxbury border, had been without a personal care attendant for a month, after her last PCA quit after just two weeks.

PCAs help her with daily activities like transferring out of bed and into the shower, dressing, cooking and laundry. The worker shortage had gotten so bad that she decided to literally take the matter into her own hands, bringing those flyers to an event hosted by the union 1199SEIU, which represents PCAs and other healthcare workers.

Two months later, she still doesn’t have a PCA.

Southard is just one of thousands of people with disabilities across the state who are struggling to find and keep personal care attendants, who help disabled people live their own independent, dignified lives out of institutions. More than 40,000 people with disabilities who are low-income rely on the MassHealth program, but advocates say subpar wages have led to a critical shortage of PCAs in recent years, leaving many vulnerable people without care they need.

The lack of PCAs is just one part of a wider shortage across the direct care industry and for services that support people with disabilities that emerged during the pandemic, as workers left for higher-paying jobs in other fields.

For some people, the PCA shortage is not just an inconvenience — it’s a matter of life and death. Charlie Carr, legislative liaison at the Disability Policy Consortium, is mourning his friend Laura Rauscher, a longtime disability advocate who worked at Smith College.

Rauscher developed massive sores on her hips because she didn’t have PCAs to help her at home. She had surgery in a hospital and went to a skilled nursing facility to recover, but never left.

“She couldn't get out because she couldn't get PCAs, and she died there, after months of waiting to get PCAs,” Carr said. “So it's not a shortage. … It's a crisis.”

A “liberating” program

The PCA program was born out of the independent living movement that began in California in the 1970s and spread to many other states. Massachusetts’ program formed in 1974.

Carr was there at the beginning. He was 21 at the time, one of 15 people living in an institution in Waltham. After the Boston Center for Independent Living was formed to facilitate the new PCA program, he moved to an apartment complex in Medford. He has lived outside of institutions ever since, thanks to the “liberating” program.

More Local News

The PCA program has shifted in recent years to give the disabled individual, known as the “consumer,” more control. PCAs are paid by the state through a contract agency, but it is the consumer’s responsibility to hire, train and fire their own personal care attendants.

Dennis Heaphy, lead researcher at the Disability Policy Consortium, lives in Back Bay and has used PCAs since the mid-1980s. Heaphy said the program allows him to live a meaningful life with opportunities he might not otherwise have.

But he has dealt with gaps in his coverage more and more frequently in recent months. Without PCAs, his quality of life suffers.

“I've gone without dinners. I've had to stay in bed,” he said.

One problem, he said, is the low wages for PCAs that aren’t adjusted for people who have more complex needs. When he advertises on Craigslist, it’s not uncommon to get very few responses.

“People who came and wanted to interview, and they look at me — I'm a quadriplegic — and the amount of work they'll have to do when they can get paid the same amount of money working with someone with half my needs get, [or get] paid the same or more money working in a store,” he said.

Advocacy for higher wages

The PCA workforce is made up largely of women of color, many of whom are immigrants. They make $18 an hour. The union that represents them, 1199SEIU, is currently in contract negotiations and is asking the state to increase pay to $25.

Disability advocates are calling on Gov. Maura Healey to agree to that pay hike and give PCAs better benefits to attract more people to the job. While she was campaigning for governor, Healey said addressing the PCA shortage was a top priority of hers. She has also proposed building a worker pipeline through more job training and certifications.

A spokesperson for Gov. Healey told GBH News that the governor has "deep appreciation" for the work PCAs do. "Our administration is committed to ensuring they are supported and currently negotiating a new contract with PCAs," the spokesperson said.

Revere resident Ellie Pagan-Vargas, a PCA user, says a pay increase would help attract people to the position, which can be emotionally and physically challenging.

“The people we used to know [who were PCAs] — they all quit because it's not worth it,” they said.

Pagan-Vargas has had such a hard time finding PCAs for the last three years that they have to rely on family and friends to help them shower, do laundry, use the bathroom and get dressed.

“My only rock is my mother and my friend, the only people that do everything for me,” they said.

Not all consumers and PCAs agree with some of the other proposed changes to the program. Heaphy and Carr say some of the proposals, like the training requirements, have caused tension between the union and consumers; they say some of those measures would just serve to increase barriers to joining an already too small pool of workers.

“This is really an equity issue,” Heaphy said. “The state should be reducing barriers to people getting employment, rather than creating barriers.”

Work done with love

Many PCAs say they find the job rewarding and want to keep doing it — yet the low pay can make it difficult to stay.

Worcester resident Janice Guzman has been a PCA for her mother for the past 25 years. She originally planned to study criminal justice and become a lawyer, but became a PCA when her mom got sick. The PCA program allows adults to become PCAs for their parents; but parents cannot be paid to be a PCA for a child who is a minor and a person cannot be a PCA for their spouse.

Her mother, a Puerto Rican immigrant, is 84 and has dementia, Parkinson’s, COPD and emphysema. “To see your mom deteriorate in front of your eyes — it’s tough,” Guzman said. “I’m her everything.”

Guzman starts her day every morning at 5 a.m., after having stayed up with her mom until 2 a.m. In the morning, she cleans their home and prepares breakfast. When her mom gets up, Guzman showers her, dresses her and gives her medication.

"This is really an equity issue. ... The state should be reducing barriers to people getting employment, rather than creating barriers."-Dennis Heaphy, Disability Policy Consortium

PCAs don’t get the same benefits as nurses in terms of pay, retirement savings or paid time off. The work, like transferring people out of bed with a hoyer lift, is physically demanding.

“PCAs have to do that alone at home. And who's going to do that when they, you know, getting paid only $18 an hour?” she said. “On a daily basis, I’ve been struggling myself, and my fellow PCAs, because day-to-day we have to think of paying a bill or putting food on our table.”

Despite the challenges, she loves the opportunity to give back to her mom.

“It's a passion that we do this. PCAs do this from the heart. It's just something that we love to do,” she said.

What happens when no one can fill in the gap

Malden resident Rhoda Gibson has been left without a PCA for as long as four months at a time. Gibson, who is 65, has no family nearby, and her friends are mostly older and not always physically able to help her.

Her housing situation has exacerbated her struggle to find a PCA. Her apartment already had pest problems, and Gibson says PCAs have quit as a result; yet because of her disability she can’t always keep up with the cleaning — it’s a difficult cycle to break.

During her periods without a PCA, when she tries to make breakfast on her own, she sometimes drops eggs on the floor, unable to clean it up for days.

“I'm in a wheelchair. I can't bend down. … So it will stay there for a while, you know? And then it might cause roaches, but I can't get it up myself,” she said.

During those periods without a PCA, she says it’s hard enough to reckon with her loss of independence, let alone face eviction.

“And I sit here and cry so much, because I'm so frustrated,” she said.

Back in Mattapan, Southard said that the daily uncertainty of getting support often leaves her in tears. She says the inconsistency has robbed her of one of her life’s ambitions.

“I have goals to become a foster or adoptive parent. I decided that that's not going to happen,” she said. “Because of PCAs — if my needs are not met, I cannot take care of another being.”

Like so many people with disabilities, PCAs are the key to her independence that she is trying to hold onto.

“I don't have backup. I don't have any family that lives nearby. It’s recently been brought to me as a possibility of supported living,” she said. “I'm not ready for that. But I need help.”

This story was informed by listening sessions GBH News held with community members. To learn more about our mission to be a newsroom without walls, and how you can meet our editors and reporters, visit our Community page .

Clarification: This story has been updated to reflect that a parent cannot be paid to be a PCA for child who is a minor.