The successful use of messenger RNA to create effective COVID-19 vaccines has sparked hope that the technology can be used for a much wider range of vaccinations. And now, as Massachusetts faces the worst flu outbreak in over a decade, Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston is one of hundreds of medical centers around the country enrolling participants in a massive clinical trial of a Pfizer mRNA vaccine for influenza.

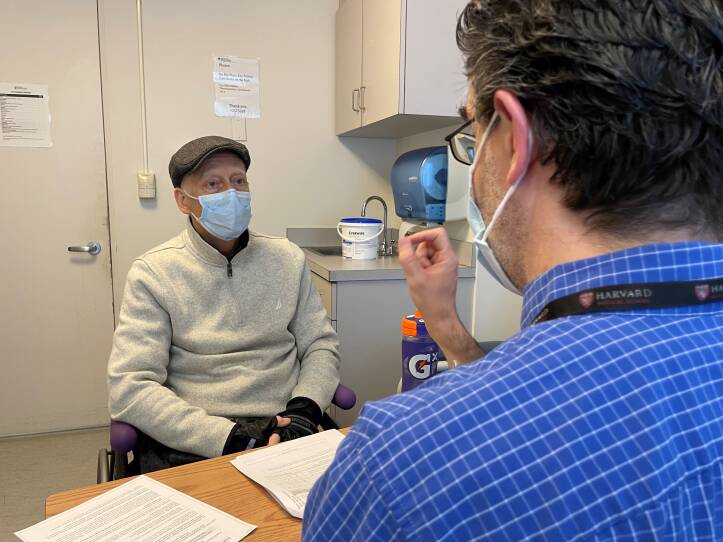

Robert Hazen of Acton was among the first local residents to enroll in Pfizer's clinical trial. He recently met with Dr. Stephen Walsh, an infectious disease specialist at Brigham and Women's, to discuss his participation.

"Everybody gets a shot of a flu vaccine,” Walsh explained. “Whether it's the experimental one or the traditional one, we don't know. You don't know until the study is over.”

The

Pfizer trial

Unlike traditional flu vaccines that use an inactivated form of influenza to trigger an immune response, mRNA vaccines use a genetic message that tells the body what proteins to produce to counteract the virus. The hope for mRNA technology is more flexible vaccines that can be developed faster.

The traditional flu vaccine

takes about six months to complete the research and manufacturing

“With mRNA, potentially, they can cut that down to two months," Walsh said.

Researchers say mRNA could be particularly effective in fighting the flu. For example, while this year’s traditional flu vaccine is a

pretty good match

"We're constantly having to chase the flu,” Walsh explained to Hazen. “And some years we do a good job. Some years we don't."

A faster timeline would allow researchers to see what strains are circulating in the winter in the Southern Hemisphere, offering a preview of what’s likely to hit North America when the seasons flip, Walsh explained.

"The advantage with the mRNA vaccine is that it can be tweaked,” said Dr. Jennifer Wang, a professor at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School in Worcester, who is leading that center’s

participation in the Pfizer trial

“So if at the beginning of the season we realized, ‘Oh, you know, we should have put more attention to a particular strain that was not predicted to be the dominant one,’ then we could make a quick adjustment to the vaccine and give it to protect more people immediately," Wang said.

Trials of mRNA vaccines are also underway for a wide range of other viruses, such as HIV.

“COVID really proved the point that the mRNA vaccines are highly immunogenic,” Walsh said. “They give most people excellent immune responses, and that translates into an effective vaccine.”

Still, there’s a chance that mRNA vaccines might not be as effective for the flu. That's according to Dr. Peter Hotez of Baylor College of Medicine.

“It's by no means a slam dunk,” Hotez said. “And we should not assume that just because it worked for a coronavirus, it's going to work for an influenza virus.”

Hotez noted that several different kinds of vaccines, not just mRNA, worked for coronavirus, and that the flu virus is a more complicated target. There are hundreds of strains of the flu, and it mutates quickly.

“So COVID-19 may not be the best litmus test for mRNA,” he said.

Since the pandemic, Hotez said, everyone’s been rushing to mRNA as though it’s a miracle technology and our expectations may be too high.

“It's a good technology. It's an interesting technology,” he said. “But like any technology, it has its strengths and weaknesses.”

For one thing, mRNA vaccines require cold storage that currently isn’t widely available in much of the developing world. And, he pointed out, while mRNA vaccines are quicker to develop than vaccines grown in eggs, they’re not the only kind of vaccine that can be developed relatively quickly. Other vaccines Hotez has worked on, including a COVID-19 vaccine used in India and Indonesia, have taken a similar time frame to create as mRNA vaccines.

“In its current form, it's somewhat faster, but it's not warp speed as advertised,” he said.

At the same time, Hotez acknowledged that mRNA vaccines do offer the possibility of what he calls a holy grail: one universal vaccine that would cover all strains of the flu.

As he got his flu shot at Brigham and Women’s, study participant Robert Hazen looked away so there was no chance he could see whether he got the new mRNA vaccine or the traditional one. He said he didn't really care which shot he received.

“For me, it's really more about, you know, helping to keep this new idea and approach, this mRNA style, keeping that moving into as many places as we can, because it seems to be so agile and so effective,” he said.

How Hazen and tens of thousands of other study participants fare in the coming months will show just how agile and effective an mRNA flu vaccine might be.