People found guilty of a crime they did not commit are legally able to receive wrongful conviction compensation from the state. But it’s not an easy task. Fred Weichel, a South Boston man released from prison after 36 years for a murder associated with Whitey Bulger’s gang, is trying to do just that — and running into hurdles. GBH News legal analyst and Northeastern law professor Daniel Medwed joined GBH’s Morning Edition hosts Paris Alston and Jeremy Siegel to talk about Weichel’s case. This transcript has been lightly edited.

Paris Alston: It wasn't that long ago that we were talking with you, Daniel, about the web of complications that can lead to wrongful convictions in the first place. But now people are having trouble getting compensated for them. So let's begin at the beginning. What was Weichel first convicted of doing?

Daniel Medwed: Before I start, I should acknowledge that I'm on the board of trustees of the New England Innocence Project, which is a local nonprofit that's been involved in this litigation on behalf of Mr. Weichel. A little disclaimer. So here's what happened: someone shot and killed a man named Robert Lamonica outside his apartment in Braintree in 1980. There weren't any suspects until an eyewitness came forward. He was about 175 feet away from the crime and he had just consumed, by his own admission, about a six-pack of beer. But he described the perpetrator's facial features to a police sketch artist who came up with a composite that in turn was used as the basis for figuring out which mug shots this witness should look at.

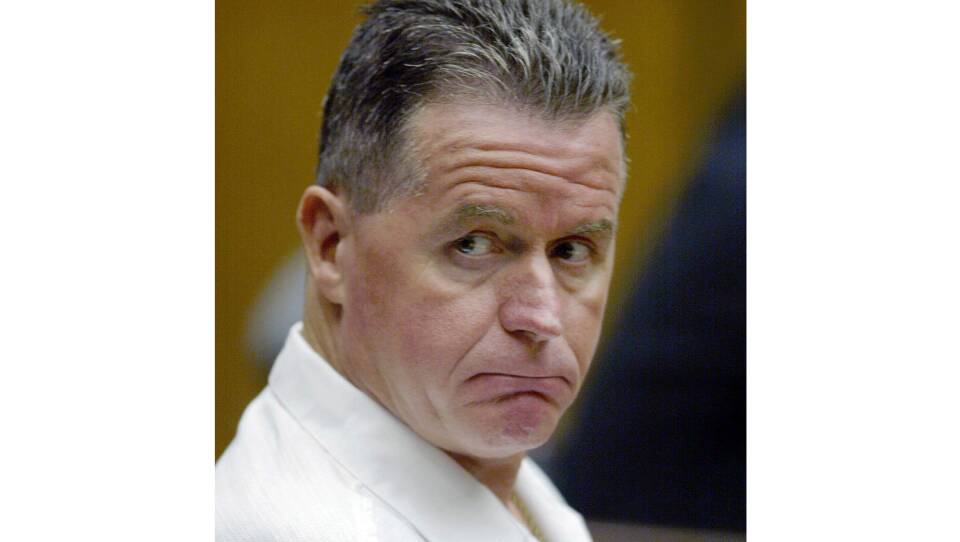

Long story short, he identified a South Boston man named Fred Weichel as the shooter. So Weichel immediately and persistently has claimed innocence. He said he was at a Boston bar drinking at the time, actually two different bars around that time, and that he's innocent. But a jury didn't buy his alibi and he was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison.

Jeremy Siegel: And then he ended up spending decades in prison, 36 years, before he was freed. What eventually led to his release?

Medwed: Well, unsurprisingly, I think the eyewitness identification evidence was the weak link in the chain of this case. I mean, it was really the only link, but it was pretty darn weak. And for years, his advocates sought to sever it. Finally, they caught a break. In 2010, his new legal team, which was pursuing post-conviction litigation, sought discovery from the Braintree Police Department. And among other things, they received a police report that pointed to a third-party suspect, and suggested that another person had committed this crime.

Now, under federal constitutional law, this is what's known as Brady material after a famous 1963 Supreme Court case that says if there's evidence that could exculpate a criminal defendant, that's favorable to the accused and is consequential to guilt or innocence, the government must disclose it to the defense before trial, to essentially even the playing field and allow the defense to have a fair chance. Prosecutors never disclosed this. So this violation provided fodder for what's called a motion for a new trial, that Weichel deserved a new trial. And in 2017, a judge agreed that this was enough to give him a new trial. Now, Norfolk County prosecutors could have retried him. They stopped short of declaring him innocent. Instead, they said, this case is too old. The evidence is stale. We're not going to expend state resources to pursue it. So that's how the criminal case was resolved about five years ago.

Alston: So, Daniel, how does the state compensation law work in a case like this one?

Medwed: For a long time, it was a very circuitous path to getting compensation. It really depended on the tenacity of your lawyers and the creativity of your lawyers, because there wasn't a law on the books that guided this process. That all changed in 2004, when our legislature passed a bill — it's now called Chapter 258-D — that is an explicit mechanism for getting wrongful conviction compensation. That bill was amended significantly in 2018, and here are some of its key features: So first, in order to get money, you have to prove that you were innocent by what's called clear and convincing evidence. Specifically, you have to show that you received judicial relief on grounds 'tending to establish your innocence.'

"For a long time, it was a very circuitous path to getting compensation."-Daniel Medwed, GBH News legal analyst

Second, you have to show that you didn't somehow contribute to your wrongful conviction in the first place, say, by pleading guilty to the crime originally, or maybe by committing some type of lesser crime that relates to the factual circumstances of this one. You basically have to have clean hands with respect to your conviction.

And third, assuming you can clear these hurdles, as well as other procedural barriers, you can receive a maximum $1 million in damages, along with free counseling services, free tuition at a state college or university and an automatic expungement of your wrongful conviction from your criminal record. So, Fred Weichel sought to pursue this relief in state court. And just this month, the case is being heard in Boston.

Siegel: What exactly is the fight over whether he should get this compensation about? I mean, you mentioned that from the beginning he was maintaining his innocence. Is this about whether he has enough evidence to prove he's innocent?

Medwed: Yeah, it's a little Orwellian. The state isn't so much contesting his innocence as they're suggesting that he was somehow involved in criminal activity related to this crime. Specifically, even if he wasn't the triggerman, according to the state, he played a role in not coming forward to the police and telling the police about another suspect, a guy named Tommy Barrett. So, according to Weichel, this is what happened: After Weichel emerged as a suspect, he got a visit from a notorious South Boston figure at the D Street Housing Projects — a guy named Whitey Bulger, who led the Winter Hill Gang, a notorious criminal syndicate, throughout the 1980s. And apparently, Bulger threatened to kill Weichel, as well as Weichel's sister and mother, if Weichel breathed a word about the involvement of this other guy named Tommy Barrett.

Now, Weichel doesn't know who committed the crime. He insists he really doesn't know. But he does know that Whitey Bulger threatened him if he were to divulge that Tommy Barrett might be a suspect. So this put Weichel in this classic Catch-22. On the one hand, he could tell the police about this encounter with Whitey Bulger and the name Tommy Barrett. That might help Weichel in terms of his trial in 1981, but it would imperil his life at the hands of Whitey Bulger. On the other hand, and this is what he chose to do, he could keep quiet, roll the dice and see how things happen at trial. Well, that gamble didn't pay off, as Jeremy pointed out. He spent 36 years in prison for a crime he didn't commit.