Black Americans first settled in Worcester when Massachusetts was still a colony. Nearly three centuries later, the city is embracing those deep roots with a Black History Trail.

Local elected officials and community leaders gathered Thursday to unveil the first five markers on the trail commemorating the city’s historic African American sites. Members of the city’s Black community said Worcester’s African American heritage has mostly been forgotten. They hope the new trail will change that.

“We have a rich history in this city. It’s about time it was recognized, publicized and showcased for all of Worcester to see,” City Councilor Khrystian King said.

City officials, historians and local Black leaders spent about four years researching and planning the project. The trail will grow to include more markers as well as a phone app to guide visitors.

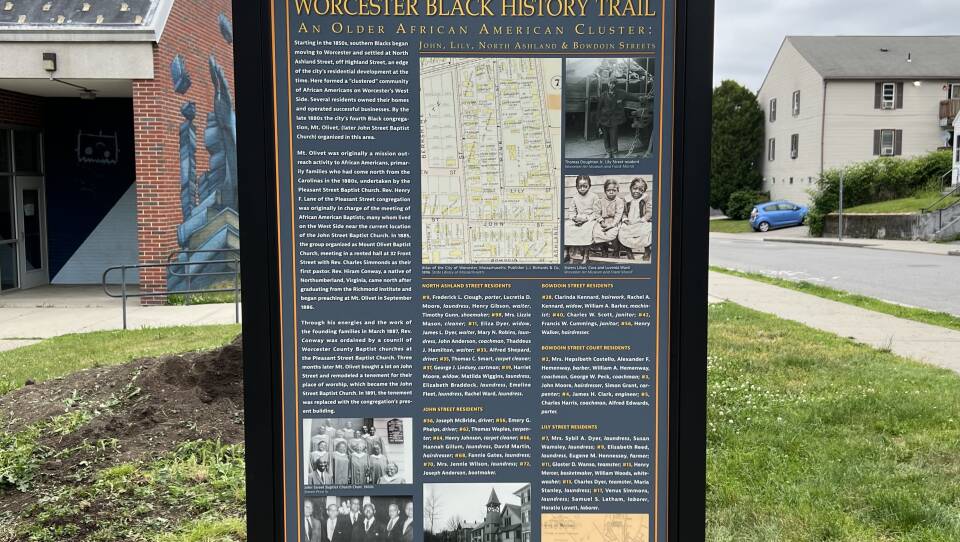

The markers, which feature photos and descriptions of African American historical landmarks, reflect the predominantly Black enclaves that used to exist around Worcester. College of the Holy Cross professor and Black History Trail committee member Thomas Doughton said Black people first arrived in Worcester about 300 years ago, before the Revolutionary War. More migrated to the city from the South into the 1900s.

Throughout that period, African Americans made up a small portion of Worcester’s total population. But Doughton said they formed a cohesive Black community. Although racist policy decisions, including the construction of Interstate 290, ultimately broke up the city’s Black enclaves, Doughton said their legacy continues in the city.

“We have families of color who have lived in Worcester now for between six and 12 generations,” Doughton said.

One of the markers along the trail recognizes a predominantly Black community at the intersection of John and North Ashland Streets. John Street Baptist Church, one of Worcester’s first places of worship for Black residents, still stands. The area also included the homes of jazz musician Freddie Bates and Samuel Langford, considered one of the greatest boxers ever .

Other markers are around the AME Zion Church on Belmont Street; Liberty and Palmer Streets area; Rejoice Newton Farmstead at Newton Square; and the 18th century residence of the Afro-Indian Hemenway family at May and Westfield Streets.

“We have a piece of history — a piece of history that anyone can walk by and they can read,” said Fred Taylor, a trail committee member and president of the Worcester Branch NAACP. “They’re gonna know [that for] 280-plus years, Black people have been in the city of Worcester.”

More than two dozen people attended the dedication ceremony Thursday, which came as the city is about to celebrate its tercentennial. Sha-Asia Medina, director of The Village, a Worcester Afrocentric cultural learning and healing center, said she appreciates that Black residents are finally receiving credit for their role in Worcester’s history.

Although many of the historically Black enclaves in Worcester no longer exist, Medina said people cannot lose sight that African Americans continue to have a strong presence in the city today. Proper recognition of Worcester's African American community involves ensuring the city is an equitable and inclusive place for Black people, she said.

"We have a stake here, and we have to be invested in making sure that this community reflects our history and culture and prioritizes our needs and children,” Medina said. “It's never really as substantial as I think Black folks would like it to be.”