Update 4/21/21 11:49am : After this story published last night, former Boston Police Commissioner Paul F. Evans and former BPD Superintendent Ann Marie Doherty issued a statement, saying the City Hall release of about a dozen pages of the Patrick M. Rose, Sr.'s internal affairs report gives an incomplete and misleading picture of police efforts to discipline Rose.

“The final result of this case was unsatisfactory in the 1990s; it continues to be unsatisfactory now," reads the statement, which was published by the Boston Globe on Wednesday. "But to suggest that there was any lapse in leadership or dedication to bring this case to a different conclusion is not consistent with the facts. Anyone who asserts that leaders of the police department neglected their duty to protect and serve is wrong.”

The statement also calls on acting Mayor Kim Janey “in the interest of true transparency,” to redact and release the BPD internal affairs divisions’ full collection of documents.

“It is difficult to believe that the City took as long as it did to release 14 pages of notices and letters associated with the investigation with very limited redactions,” the statement said.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

The highest levels of Boston Police Department leadership, including former Commissioner Paul F. Evans, were aware of the initial abuse allegation leveled against Patrick M. Rose Sr., but Rose was allowed to remain a patrolman because of pressure from the police union, according to police files released Tuesday by acting Mayor Kim Janey.

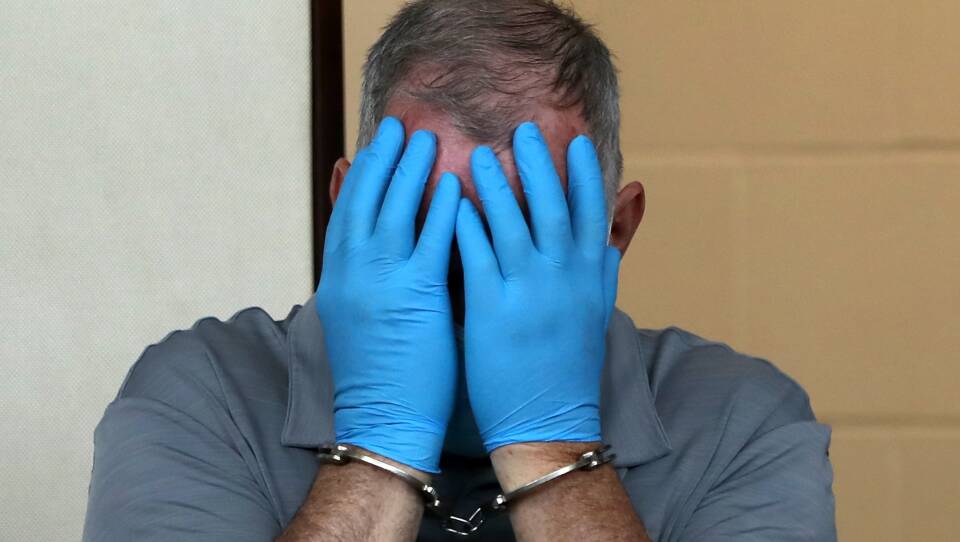

Rose now faces multiple charges of child sexual assault.

The previously confidential files from BPD's Internal Affairs Division, which were redacted to preserve the victim's privacy, shed light on the allegations against Rose. They also show that the Boston Police Patrolmen’s Association, the BPD officers union that Rose eventually came to lead, sent a letter in 1997 to Evans requesting information that would help them in “considering whether to file a grievance” over Rose’s suspension. Rose was reinstated thereafter.

Nothing in the batch of documents suggests that BPD leadership made moves to punish Rose beyond relieving him of his weapon and placing him on administrative duty for two years.

In a statement accompanying the documents, Janey said the release was intended to give “transparency and accountability” regarding the internal affairs process while also shielding the victim’s identity.

“Based on a review of former officer Rose’s internal affairs file conducted by the city’s Law Department, it is clear that previous leaders of the police department neglected their duty to protect and serve," Janey said in a written statement. "Despite an internal affairs investigation in 1996 that found credible evidence to sustain the allegation against Rose for sexually assaulting a minor, it appears that the police department made no attempt to fire him."

According to The Boston Globe, Rose was accused of molesting a 12-year-old child in 1995 but remained on the force until his retirement in 2018 — despite multiple investigations that found evidence of abuse in that instance.

Since Rose retired, five additional people have stepped forward with accusations of sexual abuse. He now faces more than 30 charges stemming from those allegations.

Boston's Office of Police Accountability and Transparency, initiated by the Walsh administration and now being staffed by Janey's, will conduct its own investigation into how the police department handled the accusations against Rose.

Janey said the “apparent lack of leadership shown by the department” in the case is “extremely troubling.”

“When members of law enforcement violate their sacred duty to protect and serve the community, we have no choice but to expose their misconduct and attempt to rebuild trust,” she added.

Rahsaan Hall, director of ACLU Massachusetts’ Racial Justice Program, could not recall an instance where city officials published documents like the ones released Tuesday in a police case. He called the move “a new standard” that Boston’s next mayor should be prepared to meet.

“This is what we expect to see, particularly when it comes to public employees who are engaged in misconduct — and especially when it is police, the ones that as a society we have entrusted with the mandate to serve and protect,” Hall told GBH News. “It’s appropriate that we have this level transparency and disclosure around prior misconduct.”

ACLU Massachusetts has sued the city and its police force multiple times, most recently last August, for what the group has called a “long standing pattern of delay” that violates state public records law.

The case, which seeks records on police surveillance and use of force at recent demonstrations, is now pending in Suffolk Superior Court.

Hall said the current scandal and the political climate validate the long-held concerns of people of color and people in low-income communities who have consistently been harmed by the police.

“Any attempt to critique the institution or these departments has been rebuked, and this type of revelation helps show why there is so much concern around the way that policing happens,” he said.