GARDNER — Beyond the barbed wire of a state prison, down a dirt road marked with “no trespassing” signs, lies a hill dotted with PVC-pipe crosses marking the graves of nearly 90 inmates.

The makeshift crosses in this state-owned cemetery bear no names to indicate who lies underneath.

The dead include men convicted of murder and sexual assault who were buried over the last quarter-century; some had spent decades behind bars. Each had no families or friends willing or able to collect their bodies, and were buried here by staff and fellow inmates under the eye of the state Department of Correction.

For some policy makers and victim rights groups, this is the appropriate ending for felons convicted of the most terrible crimes. A life sentence is supposed to mean just that.

These unnamed cemetery plots also hint at the enormous cost to the public of keeping prisoners in captivity until they die. Now Massachusetts, which has one of the oldest prison populations in the country, is looking to reduce the number of incapacitated or terminally ill inmates, potentially saving taxpayers millions of dollars.

Gov. Charlie Baker signed legislation in April that will allow some of the state’s sickest inmates to be released if they can prove they are no longer a safety risk. That made Massachusetts one of the last states in the union to offer what is often called “compassionate release.”

But the new law may not serve as a significant release valve to offset the rise in elderly and ailing inmates.

Already, Baker has proposed legislation to prohibit the release of inmates who are serving life sentences without the possibility of parole for first-degree murder, a category that includes 375 elderly inmates.

Brendan Moss, a spokesman for Baker, said last Monday that the administration wants to make sure that prisoners convicted of first-degree murder “serve sentences that match the heinous crimes they committed and are not eligible for medical parole.” Meanwhile, sex offenders would be released only under “detailed procedures established for those unique cases.”

Also last Monday, state lawmakers held a hearing to consider Baker’s amendments. Several prison advocates urged the state not to change the new law.

Joel Thompson, a staff attorney with Boston-based Prisoners’ Legal Services, said most states’ compassionate release laws are too slow and underutilized. “The Legislature got it right and should leave it the way it is,’’ he said.

Many of these men were likely sick for years before they died, hobbled by kidney failure, hepatitis C, and other chronic conditions that dramatically increase the cost of caring for them.

“Criminal justice reform in Massachusetts has lagged enormously behind the country,’’ said John Reinstein, former legal director of the state’s chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union. “The costs of this are simply huge.”

Ben Forman, research director of the nonprofit think tank MassINC, called Baker’s proposal “lunacy.”

“If they have served 40 years in prison, let them out already and don’t bear the burden of the expensive end-of-life care,” he said.

Health care challenges

About 21 miles from the Gardner prison cemetery, where visitors are not welcome, men with taut skin and thin faces lie on cots or slump in wheelchairs in a locked medical wing in the medium-security prison in Shirley.

Inmates suffering from dementia and the debilitating consequences of stroke stare aimlessly. Some are incontinent and wear diapers. A few play games, color with crayons, and do puzzles. The oldest inmate, convicted murderer Osborne Sheppard, is 94.

This looks like any other nursing home, but behind bars. MCI-Shirley has 25 beds in a skilled nursing facility and another 13 in an “assisted daily living” wing for its neediest inmates. There’s a room for up to 18 men to undergo dialysis.

“We have individuals who are full care patients that may be post-stroke or in complete quadriplegia that just require our full care — with everything — dressing, changing, and diapering,” said Elizabeth Louder, a clinical social worker and health services administrator.

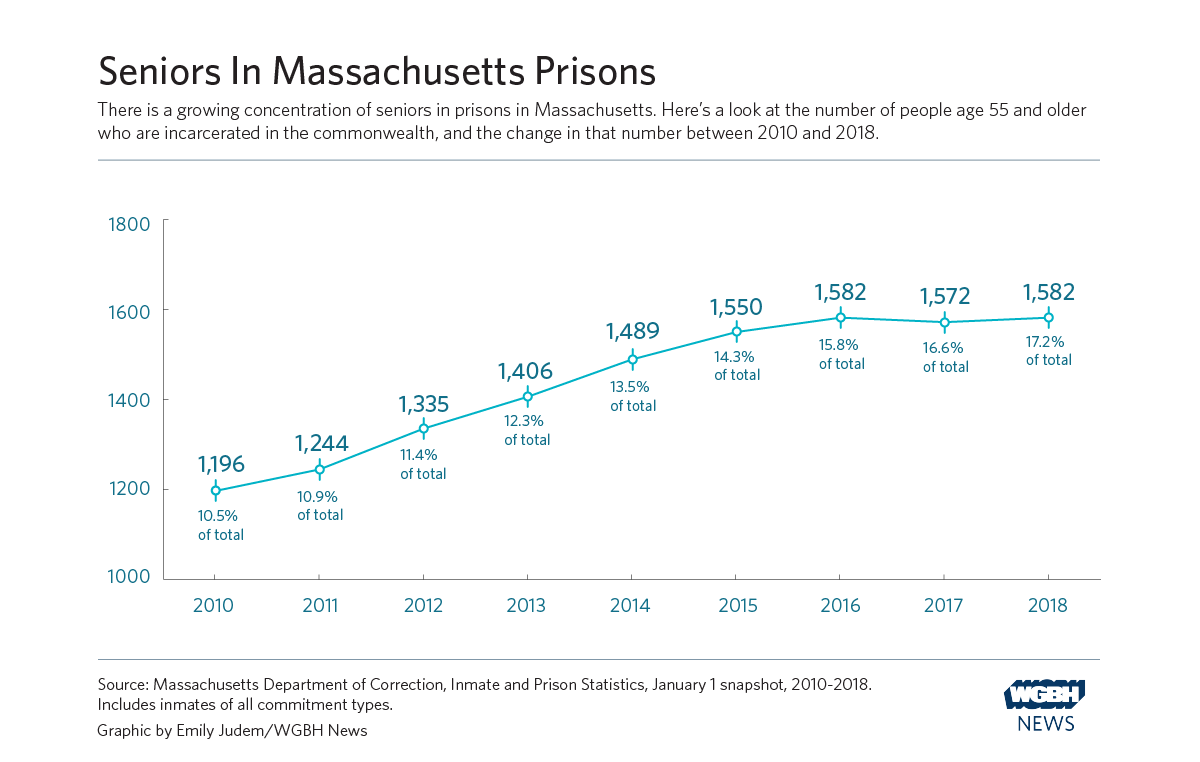

While the state prison population has dropped from 11,723 in 2012 to 9,207 as of January, the number of inmates age 55 and older rose about 18 percent over the same period, state data show. There were about 1,580 of these 55-and-over inmates in prison last year.

Other sick and aging inmates are housed in a 20-bed assisted living facility in Norfolk and the 29-bed Shattuck Hospital Correctional Unit, records show.

At 17 percent, Massachusetts’ proportion of inmates 55 and older is considerably higher than the national average of 11 percent, according to a 2016 report. The rising average age of inmates is a national phenomenon brought on by the country’s overall aging population and the strict sentencing laws of the 1980s and 1990s that kept people behind bars for decades.

Prisoners are generally considered old in prison at 50 or 55, aging more quickly than the general public because of hard living outside the walls and stress and the challenges of maintaining healthy lifestyles while incarcerated. They are more likely to have chronic diseases and suffer from dementia. They also are considered less likely to commit new crimes when released, according to state and federal data.

The cost to taxpayers of caring for sick and aging inmates can be staggering. A recent study by the Pew Charitable Trusts reported that annual costs of incarcerating inmates who are 55 and older with chronic and terminal illnesses to be at least two or three times the cost of average prisoners.

The cost to house an inmate at one of the state’s maximum-security prisons, Souza-Baranowski Correctional Center in Lancaster, averages $64,211 a year, while the state spends $283,749 per year to care for each sick prisoner being treated at Shattuck, according to state records.

Essex County officials recently reported they spent more than $2 million to guard one inmate, Raymond Wallace, at Shattuck over a four-year period while he was awaiting trial. Wallace, 41, was shot during a botched escape in 2013 and has been too ill to stand trial, having undergone multiple surgeries, court records show. In testimony last year, Sheriff Kevin Coppinger called the costs of guarding him “crushing.”

Amid mounting medical costs, a possibility for parole

Lawsuits highlight other challenges the state faces in caring for sick prisoners. In March, the DOC settled a class-action suit with a group of men who claimed the prison system failed to provide drugs to cure their hepatitis C.

The suit claimed more than 1,500 inmates suffered from the disease, a liver infection that is spread through contact with blood or bodily fluids, but only three were being treated for it. If the settlement is approved by the court, sick inmates should soon be treated more frequently and with more effective drugs, at an estimated cost of $30,000 to $50,000 per prisoner.

The agreement did not come in time for one of the suit’s two named plaintiffs, Emilian Paszko, a convicted murderer who died at age 64 of liver failure and is buried at the Gardner prison cemetery, death records show.

Another inmate, Antonio Gomes, wrote a letter to the court in April urging the state to immediately provide him medical attention, worried the disease will lead to cancer. “I am a lifer, 65 years old, and unless I can somehow overturn the conviction or obtain a reduction in penalty, I cannot get treatment nowhere else but here.’’

One avenue to reducing the costs of care is medical parole. With passage of the new criminal justice law, dozens of inmates are likely to apply for it, hoping to get out before they die.

Benjamin LaGuer, a convicted rapist housed at the Gardner state prison who has liver cancer, hopes the political winds shift his way.

LaGuer filed a petition in April to be considered for release, arguing that he meets conditions of the new law: He says he is terminally ill, does not pose a safety risk, and has somewhere to go. He included a letter from his doctor, Kevan Harthshorn at Boston Medical Center, who says LaGuer’s survival “can now be measured in months rather than years.”

LaGuer also alleges that he was wrongfully convicted of the rape of a 59-year-old neighbor in 1983 and has had an array of high-profile supporters, including former Boston University president John Silber and Cambridge defense attorney Harvey Silverglate.

Silverglate urged the state to release LaGuer, saying he poses no safety risk. “His release would likewise lift from the Commonwealth the substantial burden and rather large expense, incurred in caring for terminally ill and elderly prisoners,’’ Silverglate wrote.

George McGrath, a 70-year-old, wheel-chair bound inmate housed at the Norfolk prison, also hopes for freedom because of his health issues.

McGrath says he’s no longer the same man who helped rob a Roxbury drug store in 1968, which resulted in the shooting deaths of two people. McGrath says he has had eight heart attacks; has diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension; and has had parts of both feet amputated.

“I’ve been in for 49 years,” McGrath, who uses a wheelchair, said during a recent interview in prison. “It’s time to go home.”

And there’s Joe Labriola, a 71-year-old murder convict housed in a single cell fitted for a wheelchair at the medium security prison in Shirley.

Labriola, a Vietnam Veteran, says he did not commit the 1973 murder of a cocaine dealer he was convicted of. He has unsuccessfully petitioned for commutation but still holds out hope he may get out on medical parole.

He said when he goes to the hospital, he is supervised by two guards, and has a leg chained to the bed. “Taking a shower, it’s like running a marathon” he said. “My lungs are going. What threat would I be?’’

Willie Horton effect

Before Baker signed the criminal justice legislation in April, Massachusetts was one of only five states in the country not to have a medical parole or compassionate release provision.

The state’s reluctance to release inmates dates back to the 1980s, when convicted murderer Willie Horton raped a Maryland women while on a weekend furlough from a Massachusetts prison. His face became a staple of political ads in the 1988 presidential election, helping derail the presidential aspirations of then-governor Michael Dukakis.

More recently, state officials faced criticism in 2010 after a career criminal, Dominic Cinelli, was released on parole and fatally shot a Woburn police officer during a botched robbery.

Massachusetts officials seem to have taken a lesson from these cases. Since 2000, 769 inmates have requested commutations — or a reduction of their sentence — from the state Parole Board, but only one request has been approved by a sitting governor, state records show.

Across the United States, compassionate release programs have produced limited results. A 2013 report by the Office of the Inspector General at the US Department of Justice found that the program for federal prisoners was “poorly managed and implemented inconsistently,” likely resulting in some eligible inmates not being considered and others dying before their requests were determined.

Even without Baker’s proposed changes to the law, it’s unlikely that a flood of prisoners will be released.

Meanwhile inmates continue to be buried on the grounds of two state prisons, in Gardner and Bridgewater. The state has been burying indigent prisoners for more than a century at different facilities, including Concord and Framingham.

And state officials are making ready for them — they are even working to expand the cemetery at Gardner.

“They are starting to take some land down and clear for future plots,” said Kerry Keefe, director of treatment at the prison there “This isn’t a bad place to spend eternity, but I think you’d want someone at least to cry for you.”

The New England Center for Investigative Reporting is a nonprofit news center based out of Boston University and WGBH News. Claire Tran, Patrick Lovett, Rickie Houston, Ying Wang, and K. Sophie Will contributed to this article.

Jenifer McKim wrote this story and can be reached at

jenifer.mckim@necir.org

. Chris Burrell created the audio version and can be reached at

burrellc@bu.edu.