Shortly after arriving on the University of Massachusetts Lowell campus in the spring of 2021 on a partial baseball scholarship, Cedric Rose, a muscular 5’10” infielder from Pittsfield, began typing his observations in a diary.

Rose, a transfer student from a community college in Herkimer, N.Y., hoped Lowell would be the next step in his plan to one day play in the major leagues. Baseball means everything to him.

"It's a life to me. It's a lifestyle. It's my passion. It's everything I think about when I wake up. It's what I've done my whole life and what I surround everything by," Rose told GBH News, sitting in the bleachers of the empty UMass Lowell baseball stadium this spring.

Last year, he played in 52 of the team’s 58 games in 2022 and made the New England Collegiate Baseball League All-Star team. John Duke, the parent of a UMass student who plays on the same team, described Rose's level of play as remarkable. “One of the most extraordinary plays I saw last year was him scooping up a bunt and immediately turning and firing to second base and creating a double play.”

"It's a life to me. It's a lifestyle. It's my passion. It's everything I think about when I wake up."Cedric Rose, former UMass Lowell baseball player

But Rose’s baseball dreams hit an abrupt setback when he was dismissed from the team on February 14 by Ken Harring, UMass Lowell’s head baseball coach.

And it’s not clear why he was cut.

An email he received in March from the athletic department explaining his dismissal shed little light. “Your dismissal is based on violations of the team expectations and philosophy document that all players are required to uphold,” UMass Lowell's Athletics Director Peter Casey wrote. Neither Rose nor his lawyer has seen the philosophy document, and GBH News has not been able to obtain a copy.

It’s a case of competing narratives that are now the task of an independent investigator to wade through, and possibly the federal courts. And for the 22-year-old baseball player, a decision that was made behind closed doors could make or break his career.

Because Rose thinks the reason he lost out on his final season — the last season professional scouts could see him play — was his diary. More specifically, he thinks he was cut because he was keeping track of racially insensitive comments made by Harring, and the coach found out that Rose was writing them down.

The coach

Ken Harring’s coaching record in the America East Conference is testimony to his success. Harring was named the Northeast-10 Conference coach of the year at Saint Anselm College in 2004 before taking a job as UMass Lowell’s head coach for the 2005 season, where he's been for the last 19 seasons.

He has recruited some of the strongest players in the country, and a half dozen River Hawks have been selected in the Major League Baseball draft since Harring arrived. Under his leadership, the team moved up to play in Division I baseball, the highest level of competition in college athletics. And in 2022, Harring notched his 500th career college coaching victory.

Harring told the Lowell Sun he believes he’s had an impact on every kid he’s coached. “Every kid I’ve had — whether they started four years or transferred after one year — I’ve loved them all. I pinch myself every day that I get a chance to do this.”

But Cedric Rose has doubts about that.

He says Harring treated him differently from the other, almost exclusively white players on the team. But the head coach controls their playing time.

“Nobody else has treated me the way he's treated me,” Rose told GBH News. “And he's the one who writes our lineups. There's nothing I can do about that. There's nobody I can talk to. So, I decided the best thing to do is just write to myself.”

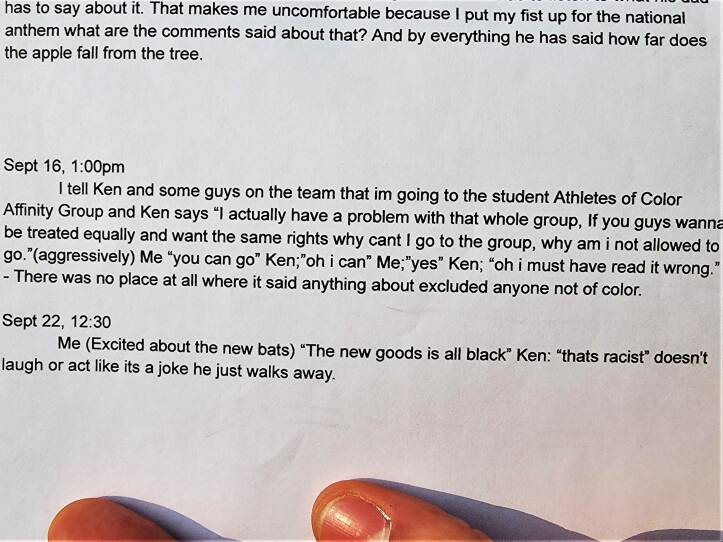

His journal entries — some undated — include suggestions that Harring was singling him out because of his race.

“I tell Ken Harring and some guys on the team that I'm going to the Student Athlete of Color affinity group,” Rose wrote on Sept. 16, 2022. “And Ken says, ‘I actually have a problem with that whole group. If you guys want to be treated equal, I want the same rights. Why can't I go to the group?’”

In the spring of 2021, Rose wrote that Harring approached him and another player of color to talk about politics. The journal entry says Harring told the players “I can complain about gas prices because that’s your guy’s guy [President Joe Biden] who did that not mine ... I didn't vote for him.’”

Rose wrote that he was mystified by the exchange.

“I have never once talked about politics with him,” Rose wrote two years ago. “He has no clue my stand on anything politics but he came up to the 2 colored kids assuming we voted for Biden and wanted to let us know that he voted for Trump.” (A review of Harring’s social media accounts shows he has retweeted messages from far-right individuals, including Candace Owens, a Black talk show host and activist who became a high-profile defender of former president Donald Trump.)

One of Rose’s journal entries recounts wearing an America East athletic conference T-shirt that said “Equality” during batting practice. “After a couple guys hit BP, Ken turned around looks at me ... with a disgusted face and tells me ‘Go take that shirt off now,’” Rose wrote.

Another journal entry describes Harring confronting Rose and another player of color at the batting cages to complain about rap music. “What is so great about rap music, all it is is glorifying drugs, gangs, violence and mistreating women,” Rose recounted Harring saying.

Harring did not respond to GBH News’ efforts to reach him for this story.

Rose shared the contents of his diary with two teammates whom he roomed with in an apartment near the sprawling campus. For reasons unknown, Rose says, in late January one of his teammates informed Harring that Rose was taking notes.

Days later, on February 8, Harring sent an urgent text message to Rose calling for a morning meeting in his office with the coaching staff.

“And they sit me down,” Rose said. “And the first thing that comes out of Ken Harring's mouth is, ‘Your teammates are coming up to us, telling us, you feel like you’re getting treated differently because of the color of your skin.’ He stares me in the eyes and says, ‘OK, let’s get transparent. Do you think I’m racist?’”

Rose said he did not answer directly but implied that he thought Harring was “prejudiced,” based on what he had observed. The exchange, described as tense, went on for more than 30 minutes. The young baseball player left the meeting angry and feeling powerless. He went home and punched a hole in a wall of the apartment he shared with two teammates. The next day he was instructed by the coach not to come to practice.

Less than a week later, on February 14, Rose was dismissed from the team.

A week after he was ordered to clean out his locker, Rose, his sister and his parents — Michelle Johnston and Carl Rose — met with Harring and other school officials at the family's request.

When people with the school asked for an explanation of the diary, family members said that Rose wrote things down as an outlet for his mental health, not as a weapon to be used against Harring.

According to notes taken by Rose’s family at the meeting, the coach scoffed at the idea that his dismissal from the team had anything to do with race and offered various reasons for kicking their 22-year old son off the team. According to the parents, Harring said he was concerned about their son's mental health, citing Rose’s alleged use of the N-word in the locker room, implicitly threatening a white roommate by playing rap music with lyrics that reference snitching, and punching a hole in the wall of his bedroom after his initial meeting with the coaching staff.

Rose said one of the assistant coaches has also played rap music in the locker room and denies ever threatening his teammates, whether through music or directly.

None of those reasons was explicitly cited in the Athletic Department’s official letter of dismissal in March.

"He stares me in the eyes and says, 'OK, let's get transparent. Do you think I'm racist?'"Cedric Rose

After an initial inquiry into the allegations, Casey, UMass Lowell’s athletic director, sent an email to Rose on March 8 upholding Harring’s decision to oust him from the team.

But after Rose and his family complained, university officials in March hired an outside investigator to get to the bottom of the conflict, which Boston civil rights attorney Ed Burley — who represents the family — said is meaningful.

“The university looked into it and they found that that it had sufficient merit to open a full investigation,” he told GBH News.

The university issued a statement to GBH News, saying, “UMass Lowell is committed to maintaining an inclusive and welcoming environment for its entire campus community. Just as it does for any allegations of discrimination, the university is investigating this matter in a prompt, fair and confidential manner.”

One incident, two stories

People in Rose’s life describe him as a skilled and affable player.

Brent Edmunds, who was an assistant baseball coach at UMass Lowell until he left the team last year, described Rose as “very, very talented” and someone “who put in a good effort.”

“He was well-liked by his teammates. You know, never — never really showed anything negative,” Edmunds said in a telephone interview with GBH News.

One of Rose’s teammates — speaking anonymously for fear of “being taken out of the lineup” and hurting his baseball career — echoed Edmunds’ characterization, saying, “Cedric got along with everyone.” He said he often heard Rose complain about being “treated differently” by Harring.

Rose’s father, Carl, is Black. His mother, Michelle Johnston, is white. She said she believes her son, and believes race is at the core of why he was kicked off the team.

“As a mom, a white mom of a young man of color, how do I support my son other than to stand behind him?” she said. “This literally started as him [the coach] learning about a journal that Cedric was only doing to help himself work through stuff. And it led to a coach trying to protect himself.”

But Ann Hardy Draper of Lowell doesn’t buy it.

Draper is the unofficial “den mother” for the River Hawks. Her son just wrapped up his last year on the team.

“I’m coming to the end of the fourth season that I’ve been around the team. I’m usually the one that sends out emails about changes in schedule or organizing group gifts and things like that,” she said.

She dismisses the accusations leveled at the coach and said she believes the Roses are using the issue of racism to “smear” Harring. Based on conversations with other parents and team members, her understanding is that Rose was dismissed “after an incident where he had torn apart the apartment he lives in with two other players, another one of whom is also a minority player. He made death threats. And he would play really loud music and crank it louder when it talked about killing white people.”

"If Ken was a racist, in my opinion, why did he recruit Cedric? Why?"Ann Hardy Draper, parent to a UMass Lowell player

Rose denies threatening anyone.

“I never heard my son come home and say that Cedric had brought up anything about there being a racial component or about being treated differently at all when he was let go from the team,” Draper told GBH News.

Draper also said that race did not come up in a private Facebook exchange she had with Michelle Johnston after Cedric left the team, but Johnston raised it subsequently in a public online forum.

“The parents I've spoken to are disgusted [about the allegations of racism], as disgusted as I am,” Draper said. “First of all, if Ken was a racist, in my opinion, why did he recruit Cedric? Why?”

She added: “If you really thought the coaches and the athletic department were racist, why would you want him back on that team?”

Cedric’s father, Carl Rose, said there have been other racist incidents at the university that have deeply impacted his family. Most disturbing, he said, was the annual “Hot Stove” team fundraiser in February of last year attended by parents, the coaching staff and team members that featured a white comedian. The comedian made Carl Rose, the only dark-skinned man in the room, the butt of racist jokes, causing “extreme discomfort” for him and his family.

“I was upset, embarrassed,” Carl Rose said. “And the worst part was after he was done, Ken came over to me and put the light back on me saying, ‘Oh, I know, Carl, you felt uncomfortable, because I sure did!’”

Draper was also there that night, but she remembers the incident differently.

“His jokes got progressively ugly and racist,” she said. “It was so embarrassing. Ken got out of his seat and went right over to the table where Cedric’s parents were, apologizing up and down. To their credit, they said they understood that it wasn’t [Ken’s] fault.”

The incident weighed heavily on the family, even though Carl Rose said his son was never an activist or very conscious of racial issues.

The sport

Still, for a young Black man, simply stepping onto a baseball field is a measure of activism. There are very few Black collegiate baseball players in the country.

“It is a scarcity, to say the least,” said Noah Jackson, an associate head baseball coach at the University of California-Berkeley, who, as a Black coach, is also a rarity in college baseball.

“It is still a sport that is a pay-to-play sport for a lot of kids,” Jackson said. “It costs an exorbitant amount of money to play summer travel baseball, and then it costs an exorbitant amount of money to come to college and play baseball because you still have to pay since there are no full scholarships.”

Jackson said racism in sports also cannot be dismissed as a factor for the scarcity of Black athletes playing the game today.

In Division I men’s baseball, nearly four in five of the student athletes are white, according to a 2021-2022 report compiled by The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport. Only 4.2% of players were Black or African American. And the lack of representation on the college level on the field and in coaching is reflected in the MLB. According to TIDES, 7.2% of MLB players were Black on Opening Day last March.

Cedric Rose said he feels a personal responsibility to reverse this trend in baseball.

“I’ve never had too many African American teammates,” he said. “I think the most I’ve had on one team at one time was, like, four. So, it speaks volumes going out there and proving that we can play at a high level. It means a lot.”

UMass Lowell’s athletic department has been lauded for its efforts to establish inclusivity and equity. It scored a perfect 100 on the NCAA's 2022 Athletic Equality Index, one of just 15 Division I athletic departments to do so, according to the NCAA. Casey, the athletic director, was quoted in a UMass Lowell press release last year, saying, “I am so proud that we continue to be among the leaders in the country for diversity, equity and inclusion, helping to set a standard in college athletics, but I know that there is always more work that can be done and we must continue to push ourselves in this area every day."

The Rose family attorney, Ed Burley, who is chair of legal redress for the local NAACP, said he plans to file a formal complaint in federal court on behalf of the family following the expected release of the university’s investigation. He told GBH News he would like UMass Lowell to live up to its reputation, but believes the Harring affair flouts the school’s promised goals of equality.

“Cedric, by keeping a diary, has engaged in protected conduct, which is complaining or memorializing either harassment or hostile work environment claims,” Burley told GBH News. “And then for doing so, he’s been retaliated against.”

Meanwhile, the baseball season has ended and Cedric Rose did not get to play this spring. That meant the collegiate and professional scouts did not see him on the field.

But he said he is determined to find a way to return to the game. A few weeks ago, Rose graduated with a degree in economics from UMass Lowell, but even as a college graduate, he still hopes to be seen by other scouts.

Now, he is playing occasionally with a summer league. He said he hopes that will lead to an invitation to play regularly, somewhere.

“A couple of weeks into the summer, people [on summer teams] will start dropping off left and right,” he said, “whether that’s injuries, whether they hate where they are and just want to go home. And hopefully I get a phone call to go play baseball, and then I’ll leave that day.”