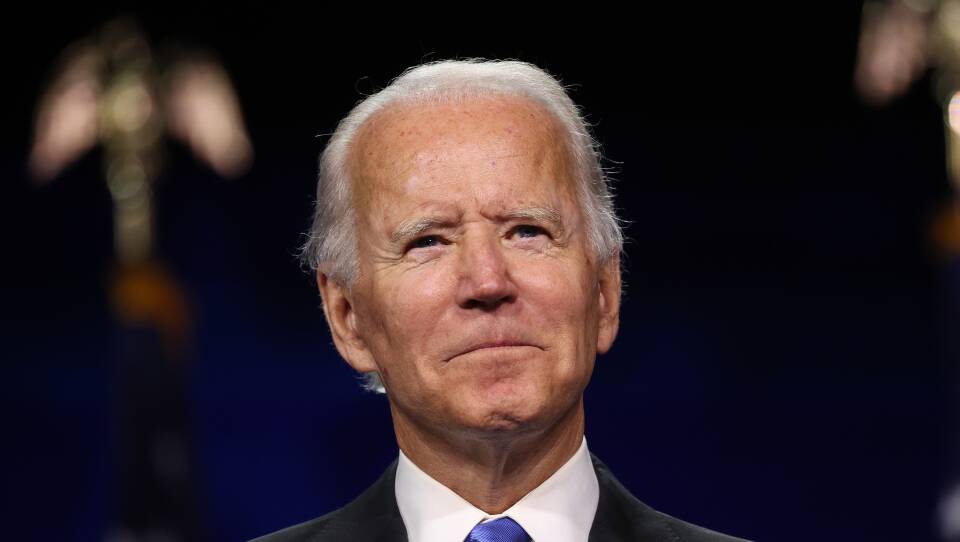

President Biden's words on CBS's 60 Minutes this week took many people in Massachusetts and around the country by surprise.

"The pandemic is over," Biden said.

"We still have a problem with COVID. We're still doing a lot of work on it," he added. "But the pandemic is over."

As local public health experts and others focused on COVID-19 gear up for what many worry could be yet another fall surge of the virus, they say the pandemic doesn't feel over. And some worry the president's comments could lead people to let their guard down and serve as a signal to Congress that additional federal support for the ongoing COVID response isn't necessary.

“The pandemic is over. We still have a problem with COVID. We’re still doing a lot of work on it. But the pandemic is over,” President Biden tells 60 Minutes in an interview in Detroit. https://t.co/7SixTE3OMT pic.twitter.com/H08ChdHwVq

— 60 Minutes (@60Minutes) September 19, 2022

Dr. Lakshmi Ganapathi, who is a pediatric infectious disease physician and public health researcher at Harvard Medical School, disagrees with the president.

"Nationally, we're still seeing an average of 400 to 500 daily deaths," she said. "And at this pace, COVID is going to be one of the top three killers in the country. And this is excluding what might potentially be a much bigger surge this fall into winter."

COVID cases surged in the fall of 2020, and then again last November as the Delta variant took off.

"I think we can all collectively recognize that it's not 2020, that substantial gains have been made in the pandemic, but that there is still a lot more left to do," Ganapathi said. "Because what we are accepting as normal at this point in time, objectively speaking, is actually a huge number of deaths, and not to mention really the disability ... because of long COVID."

The White House has been attempting to get Congressional support for more than $22 billion to support the nation's COVID-19 response, and Ganapathi and other health experts say they worry that the president's comments might make that pitch even harder.

Ganapathi noted that Biden's comments were broadcast just hours after hundreds of people lined up at a clinic in Boston's Franklin Park to receive COVID booster shots.

"And I do worry that declarations like this undermine efforts like that," she said.

Low vaccination rates persist

In Massachusetts, well over 90% of adults have received at least one vaccination shot, but the percent of those who have received booster shots — which became available to all adults nearly a year ago — is notably lower. The state's most recent weekly report, published today, shows less than half of people in their 20s have gotten at least one booster; just over half for people in their 30s; and 59% for those in their 40s. And pediatric vaccination rates have been slow to pick up. Only 16% of kids under the age of four have gotten at least one shot so far. And racial and ethnic disparities in vaccination have persisted.

"The United States has the lowest vaccination rate of high income countries, it has the lowest booster rate of high income countries, and it has the highest death rate by far over the past year," said Julia Raifman of the Boston University School of Public Health, who leads the COVID-19 U.S. State Policy Database . "And if this is where we're allowing our response to end, then we're all in enormous trouble."

For many Boston Public School parents who nervously sent their kids back to classrooms earlier this month , the pandemic doesn't feel over.

"Declaring it over is giving people mixed messages," said Sarah Horsely of the group BPS Families for COVID Safety. "Because at the same time, we're trying to get folks to get vaccinated, get boosted. And so saying that something's over just lets people off the hook. Like, 'okay, I don't have to worry about it.'"

BPS Families for COVID Safety and several other community groups sent an open letter to city and school leaders at the beginning of the school year, calling for school vaccine clinics, data-driven mask policies, investments in air filtration, and other interventions.

Horsely said it's impossible to know how many cases are spreading in classrooms.

"Last year, of course, we had pool testing. So all the students [that] families gave permission for were getting tested on a weekly basis. But now instead of that, we just have symptomatic testing," she said, noting that a lot of people who have COVID don't exhibit symptoms. "So we're missing a lot of cases. And also, we don't have universal masking anymore. So we feel a little bit like we're flying blind."

The impact on public perception

For some whose lives continue to be turned upside down by the pandemic, the suggestion that it's over is offensive.

Jennifer Ritz-Sullivan lost her mother to COVID-19 in December 2020. She now works with the nonprofit group Marked By COVID , which includes people who have lost a loved one to the virus, as well as people suffering from long COVID.

Ritz-Sullivan says she is immuno-compromised, and she worries people will wrongly take Biden's comments to mean they no longer need to take precautions.

"It's harmful and hurtful and disgusting. [Those] are the words that just constantly come to mind, that the president would make such a remark when thousands of people are dying in the U.S. weekly. Like, why? Why would you say something like that?"

But Dr. Rachael Piltch-Loeb, a research associate at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, says Biden's comments are unlikely to change the behavior of many people in a polarized society. Many are already committed to getting vaccinated, she said.

"On the other hand... there are people who will have perceived the pandemic to be over for probably a year now."

Those people, she noted, were already unlikely to get vaccinated.

"And so my perception is that the comment that the pandemic is over is likely really not swaying the needle for either of these two poles, and perhaps having a very limited effect on the middle," she said.

Personally, Piltch-Loeb said she doesn't feel comfortable saying the pandemic is over.

"Because I don't feel comfortable that this is the level of... disease burden that we have to live with," she said. "That being said, in my day-to-day life, I'm not taking the same level of precautions that I was months ago or even years ago. Masks are far less normative, you know. Social distancing is out the window."

But from a national perspective, she said, "I'm not yet there, because I think that we have yet to see what the the fall and winter will look like in terms of the burden on our health care system, which is ultimately my biggest concern moving forward."