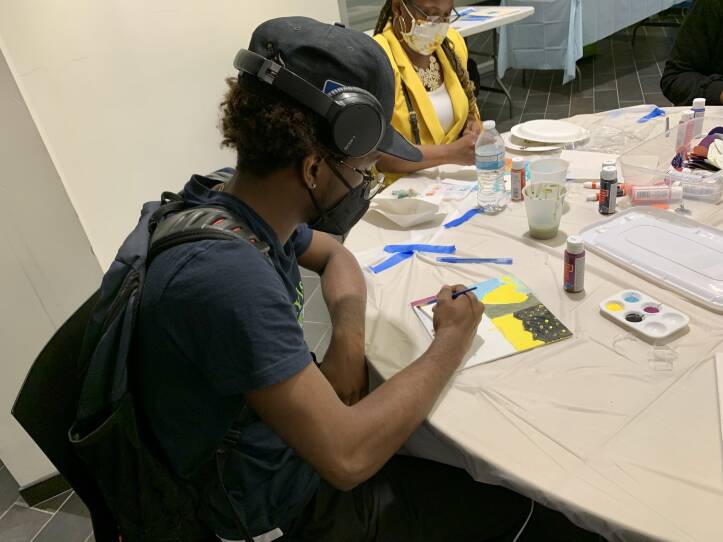

At an evening gathering in Roxbury, about 100 teens sit creating images at tables covered with brushes, acrylic paint and canvases split into four sections: spiritual, emotional, physical and mental.

“There's a lot of people who don't know how to express themselves through words, so we’re sharing how we feel through painting,” said Vanessa Lopes, 15, who has painted a bandage covering a jagged crack across the canvas.

This art exercise last month was organized by the Center for Teen Empowerment, as part of the nonprofit's Peace Week, a series of events focused on mental health awareness for young people from Boston's communities of color. “Young Black and brown kids are carrying this fear and anxiety about what they're seeing happening in the world, and no one's creating a space for them to unpack that,” explained Abrigail Forrester, the center's executive director.

Young people in Boston's communities of color were struggling with mental health issues before the pandemic sparked a crisis that increased the need for services, which were already in short supply. Now, community leaders say the kids who need help the most face long waits or can't find therapists or counselors.

At the Boys and Girls Club of Boston, director of operations Eric Rivas fields requests for help from young people, whose names languish on waiting lists for months or even years.

“The tide has gotten bigger and bigger and there's nothing to stop it, there’s no canal to open it up,” Rivas said. “It’s just piling on.”

Black and brown children, particularly ones from communities with higher rates of poverty and crime, face a distinct set of mental health challenges, according to a study published in JAMA Pediatrics. Last year, a coalition of medical leaders declared a national emergency for children and adolescent mental health resulting from the impacts of the pandemic. The crisis exacerbated poverty, housing and food insecurity, and illness and death due to COVID-19, factors that disproportionately affect young people of color, who have half as much accessto mental health services as their white counterparts.

Some clients give up over time, with consequences that can be devastating.

“It’s life and death,” Rivas said. “It could be the difference between them not committing acts of violence or something as minimal as stealing or being more focused in school, all the way up to somebody that’s going to do something dramatic because they don’t get the help they need and feel like it’s the only route to go.”

Reports of suicide attemptsrose nearly 80% among Black adolescents between 1991 and 2019, while the rates did not significantly change among other races and ethnicities during that period.

Black children and adolescents who died by suicide were more likely than white youths to have experienced a crisis in the two weeks before they died, according to a2020 government study. They were also more likely to have had a history of suicidal ideation or a family relationship problem.

In the past two years, Shonna Alexander of Dorchester lost two loved ones to suicide: a 16-year-old cousin and her son's 22-year-old best friend.

“They feel they have no other way to turn or don't know what to do,” Alexander said. “It’s just sad.”

Alexander works with young people as the patient and community relations manager at Upham's Corner Health Center in Dorchester. She and other advocates do what they can to meet regularly with kids in crisis, but she says it can’t replace weekly sessions with a therapist her patients can trust. Like Rivas, Alexander said it has become nearly impossible for her patients to access the care they need.

“You're either on a waiting list or have to be referred out to be put on another waiting list, and it gets to be a year or two,” Alexander said. “That's just way too long.”

It takes a lot of vulnerability to ask for help, Alexander says, particularly in communities that historically distrust medical systems and attach a stigma to seeing therapists.

“Growing up in a Black household, that was always a thing, that therapy is negative or it’s seen as negative,” Alexander said. “Some people might be in therapy and not tell anyone because they don’t want anybody to think they’re weak. There’s a lot of shame there.”

But even those who are ready to ask for help are struggling to get it, Rivas said.

“We have Black boys who eventually become Black men that can't get help at that age,” Rivas said. “A lot of this is deeply rooted from early on in their lives. If we can't find therapy for a young boy, what chance do they have as a grown man?”

Rivas said resources need to come from people who understand the experiences these kids are going through, and without available outside resources, that responsibility falls on the adults in their lives.

"The people who are getting through it are the people that have a strong community around them," Rivas said.

As a youth leader at the Center for Teen Empowerment, a poet and an active member of her community, Lopes said she — and other young people — have a role to play in healing, even if outside resources are scarce.

“Sometimes I feel like no matter what work we do, there’s still going to be trauma,” Lopes said. “But I'm putting my voice out there to help.”

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255) or use the Crisis Text Line by texting “Home” to 741741. More resources are available at SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources.

This story emerged from listening sessions GBH News held with community leaders in Roxbury and Dorchester.