Medical professionals in Massachusetts are calling on the FDA to rescind a longstanding policy that bars most gay men from donating blood.

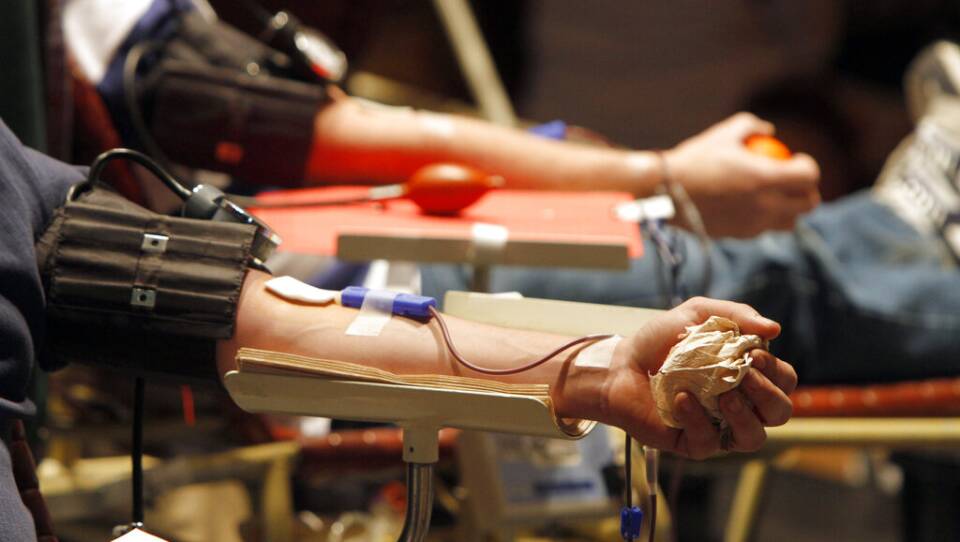

The call comes in the middle of what some are calling a national crisis over the dwindling supply of donated blood. Some Massachusetts hospitals have begun making plans for how they would respond if they were to find themselves without enough blood for all patients who need it.

The request came in a statement released Wednesday by the Massachusetts Medical Society and the Fenway Institute, the research and policy arm of Fenway Community Health Center, which serves a large number of LGBTQ patients.

Current FDA policy prohibits men from donating blood if they've had sex with another man within three months. But researchers and advocates argue that the ban does not account for screening tests that have been developed since the donation ban was first put in place, and that there are many circumstances — such as long-term monogamous relationships — where a man having sex with another man may not put him at risk for contracting HIV.

"It's true that there's a higher prevalence of HIV among gay and bisexual men, but the vast majority of gay and bisexual men don't have HIV," said Sean Cahill, director of health policy research for the Fenway Institute. "And so this kind of puts out this idea that HIV is a gay disease, and I really do think it contributes to stigma and discrimination against gay men."

Cahill said, as a gay man, the policy prevents him from giving blood.

"We have good blood that could save somebody's life in an emergency situation, or if they have a disease where they need a broad blood transfusion," he said. "And it's just really sad that we're not using that blood to save people's lives right now, when people need it."

The FDA instituted a lifetime ban on men who had sex with men from giving blood in 1983 out of a concern that their donations could lead to the spread of HIV in the early years of the AIDS crisis. In 2015, the policy was changed to allow gay and bisexual men to give blood after a year of no sex with men. At the beginning of the pandemic, facing severe blood shortages, the FDA shortened the required period of celibacy to 90 days.

"We're going in the right direction, and we certainly commend the FDA for the progress made," Cahill said. "But we'd really like to see them shift from a blanket policy that says a whole group of people are high risk to really a much more science-based policy."

Donated blood is now screened for HIV, Cahill said, and he argues scientific advancements since the lifetime ban was put in place have made the policy irrelevant.

"We didn't have nucleic acid testing [when the ban was instituted], but we've had it now for more than a decade and we're using it to test every unit of blood," he said. "So that's another technological reason why this policy is really out of date."

Cahill co-authored a paper in the New England Journal of Medicine last year looking at the results of a decision by the United Kingdom to drop a similar ban, and calling for the United States to do the same.

Cahill added the ban can put gay and bisexual men in a difficult position when blood drives are held, forcing them to disclose their sexuality, or seem like they're choosing not to participate in an altruistic activity.

Janson Wu remembers the first time he learned that he was not able to give blood because of his sexuality, at a blood drive in college.

"That feeling of being judged, being told that I was unworthy in some ways, in the middle of a busy room with many other people waiting in line to donate blood, that's something I still remember today," said Wu, who is now the executive director of the non-profit GLBTQ Legal Advocates & Defenders (GLAD).

"As a gay man, there is something that strikes a deeply painful nerve by being told that your blood is tainted, that the blood that courses through you is quite literally worthy only of being discarded," he added.

When asked about the agency's current policy, an FDA spokesperson pointed to a study it is funding called ADVANCE to determine if a change in the policy could be made while maintaining the safety of the blood supply.

"This study, being conducted at community health centers in key locations across the United States, could generate data that will help the FDA determine if a donor questionnaire based on individual risk assessment would be as effective as time-based deferrals in reducing the risk of HIV," an FDA spokesperson said in a written statement.

Dr. Richard Kaufman, the medical director for the transfusion service at Brigham and Women's Hospital, wants to see the results of that study before the policy changes. While most men who have sex with men do not have HIV, Kaufman said, people in that group do make up the majority of HIV patients. And, he pointed out, there's a short window of time — 9 or 10 days — in which an HIV infection wouldn't show up in tests of donated blood.

"So that if you acquire an HIV infection and then donate, let's say, five or six days later, it's possible to donate to an infectious unit," Kaufman said.

Kaufman added that he believes some simple screening questions, such as those now being used in the United Kingdom that flag potential risks such as recent new sexual partners, could prevent an increase in donations of HIV-positive blood. The ADVANCE study, he said, will show how effective those questions are.

"So we certainly agree with the spirit of that letter, but I do feel like it's necessary to obtain some more data to be comfortable that the risk of HIV transmission transmission will not increase if the U.S. were to switch to an individualized risk assessment," Kaufman said.

It could be years before those study results are published, though, and Dr. Carole Allen, president of the Massachusetts Medical Society, argues that it's unreasonable to wait in the middle of a crisis.

"It's always good to get more information, so if they're analyzing different questionnaires and how efficacious they are, great, let's keep doing that," Allen said. "But meanwhile, there's the blood shortage, and there are people with either acute bleeding or who have chronic diseases like sickle cell anemia or cancer or chronic anemia who need blood, and who may be adversely affected now. So if you weigh the risk benefit, I think having more blood is is the main priority right now."