More than 7,000 people have died in Massachusetts from COVID-19. In Boston, data show the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on some of the city’s minorities. Of the cases wherein race and ethnicity is known, nearly 40 percent are Black. These lives lost are much more than a number — they're individuals with fascinating lives and people who loved them. We're remembering and sharing the stories of some of the people we have lost in a series titled "Lives Remembered."

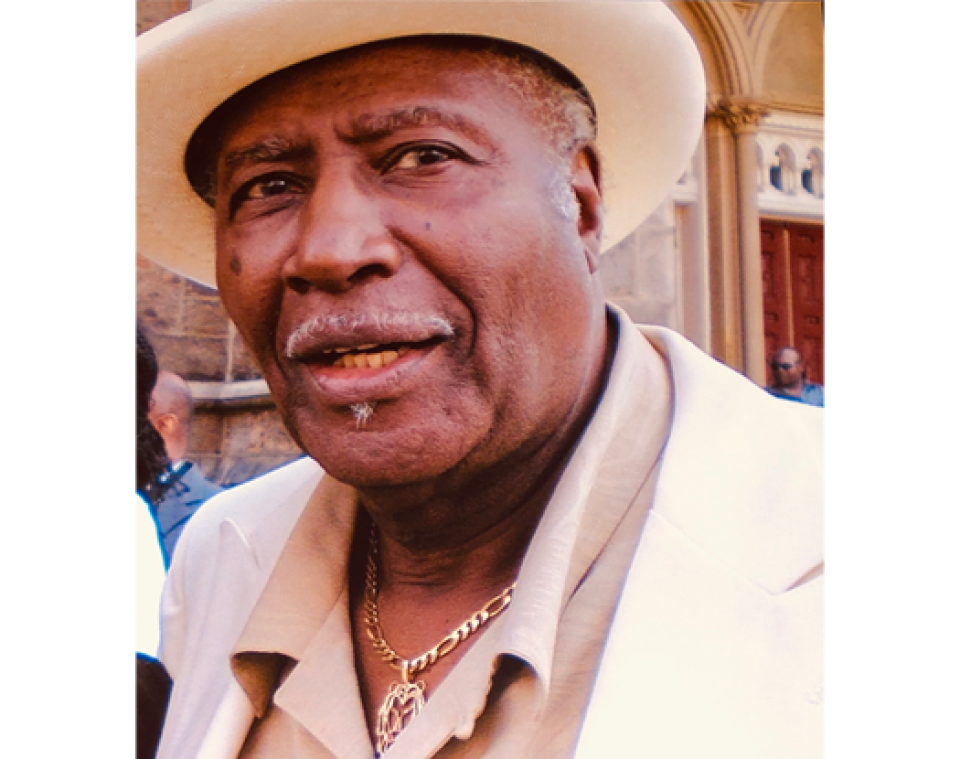

Family members of Jerry Williams say he was the old-school, family-loving patriarch of their clan.

He moved from Birmingham, Ala., to Boston with his wife, Bobbie Jo, in the 1950s as part of the Great Migration — a period wherein millions of African-Americans left the Jim Crow South for more work opportunities.

The couple, which eventually settled in a house on the border between Dorchester and Roxbury on Holborn Street in Boston, had four children — Michael, Sharroll, Antoinette and Taunya — nine grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Bobbie Jo had just finished high school at the time of their wedding on July 14, 1955. She said her instincts told her she could build a life with Jerry. She saw his strong work ethic when she met him while he was working at a local apothecary in downtown Birmingham. She knew he was family-loving when she saw how he cared for his mother, and for her.

“I think a girl can sense sincerity in a man,” Bobbie Jo said in an interview with WGBH News. “By the way they talk to them, by the way they treat them.”

Jerry, a dedicated provider for his family throughout his life, died of COVID-19 on March 30 at Brigham and Women's Hospital, where he had been admitted for a little over a week. He was 85 years old. His wife said it's possible Jerry contracted the illness from church, where another member of the congregation was infected.

Bobbie Jo said when they moved to Boston, Jerry hustled to make sure his family didn’t want for anything, and that they had as many opportunities to advance as he could provide. He earned money making investments, doing domestic cleaning work and driving a taxi cab, even after his application for a highly coveted medallion was denied. Nothing stopped him from providing for his family.

“Whatever I wanted to do, he made sure that it would happen,” Bobbie Jo said, pointing to the support he gave her as she pursued a nursing degree and then a health care administration degree from Emerson College. “He would always be supportive [and] come up with money.”

Michael Williams, Jerry’s only son, said his father was reliable and slow to anger. He recalled that his father’s calmness was reassuring to him and his family throughout the time of turmoil in the aftermath of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination.

“We lived on Holborn Street, which is right off of Blue Hill Avenue,” Michael said. “And at the time, there was looting [and] there was rioting. He was just really calm, never seemed to be out of control, never panicked. And so, it was soothing and calming.”

Michael Williams Jr., Jerry’s grandson, said his “granddaddy” did not have many hobbies. He loved to walk and take road trips, watch sports and talk trash about the New England Patriots. Basking in the love of his family, Michael Jr. said, was probably Jerry’s favorite pastime.

“[He] definitely enjoyed spending time with his grandchildren, and just celebrating. Celebrating and enjoying life. Those are things he was adamant about doing,” Michael Jr. said.

Michael Jr. was inspired by his granddaddy’s resilience, he said. Jerry had survived a life in the Jim Crow South. Then he thrived driving a cab in Boston, when the city was still overtly racist, never daring to cross into places like Carson Beach, where all people now walk freely. Jerry told him that he could thrive, too.

“’Because you’re stronger than that,’” Michael Jr. recalls his grandfather telling him. “’Use me, use your grandmother as an example of what it takes, and also [of the] strength that’s in you, because you come from us. Let that be your light to a brighter path.’”