On a recent Friday afternoon, an Arlington family's home kitchen was buzzing with activity. Leila Forman grabbed two balls of cookie dough out of the fridge, while her husband, Chris Mulvey, reached for sprinkles and cookie cutters in a cabinet.

The family, along with their sons Asher, 6, and Hudson, 4, commenced making sugar cookies with their au pair, Angelica Scarpelli. But first, the boys insisted on putting on a breakdancing performance. Scarpelli, 22, brought up the song "Brass Monkey" by the Beastie Boys on her phone and synced it to the kitchen’s stereo.

Forman, a midwife, often works 12-hour shifts overnight. Mulvey leaves for his job as a nurse practitioner before dawn. Scarpelli helps manage the children and household.

“It's crucial for us to have the extra body and it's crucial to have the flexibility of somebody else to help out here and there in pockets,” Forman said.

But this comfortable, family-oriented source of childcare is now in jeopardy for the household. A federal appeals court ruling earlier this month mandated that au pairs' pay be increased to match the state minimum wage of $12 per hour, sending hundreds of Massachusetts families into a tailspin about how they will be able to afford to keep the au pair they — and their children — have welcomed in and depended on.

Forman and Mulvey say that having an au pair — Scarpelli is the family's fourth au pair in five years — has, until recently, been affordable in a state that has the highest cost for childcare in the U.S . Up until this month, they paid Scarpelli $195.75 a week to help take care of Asher and Hudson. When a family applies to host an au pair, they often have to pay close to $10,000 in fees up front to an au pair agency.

“It's actually cheaper than day care, depending upon how much day care you're using. I mean, you do absolutely have to have a spare bedroom,” Mulvey said. As of 2018, there were 1,530 au pair visas in Massachusetts.

Along with a bedroom, the family provides meals, a cell phone and car insurance. But for Scarpelli, the real payoff has been the opportunity to improve her English before applying to graduate schools.

“I took the decision to come here to learn English and improve my language,” said Scarpelli, who arrived in Arlington in September.

Traditionally, the national au pair program has been marketed as a year-long cultural exchange that provides up to 45 hours of live-in childcare a week under the J-1 Cultural Exchange Visa Program.

In 2014, the state passed the Massachusetts’ Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, which mandated that au pairs be included as domestic workers and receive compensation as such. But two years later, the Cambridge-based agency Cultural Care Au Pair, along with local two families with au pairs, sued Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey, arguing that au pairs are here under a federal program and should be exempt from the state requirements.

In the three years since, au pairs have not been included in the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights as the case has made its way through the courts. But on Dec. 2, a three-judge panel of the 1st Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston dismissed the suit, ruling in the attorney general's office's favor. That enacted the rule that au pairs must be paid the state minimum wage of $12 an hour.

Because of the ruling, Scarpelli’s weekly salary has more than doubled. It’s not in the Mulvey family’s budget, but for now, they have to make it work.

“For some period of time, it will just be an additional expense — and source of stress,” Chris Mulvey said.

But au pairs, typically young women far from home, are not always treated well. Claudia Villamizar was 24 when she moved from Colombia to Newburyport, Mass., to work as an au pair about a decade ago. She said at one point, her host family failed to pay for extra hours she worked and when she complained, they cut off her phone and internet access. That left her without any way to contact her family back home.

“My parents were so worried. ‘What was going on? What happened? Why you don't contact us?’” Villamizar recalled.

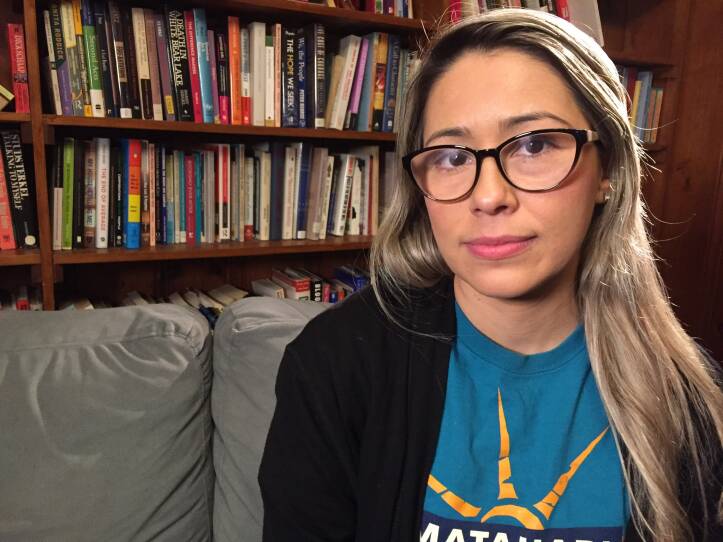

Villamizar volunteers with the Matahari Women Worker’s Center, which pushed for the passage of the Massachusetts Domestic Worker Bill of Rights. She said her experience was traumatic, but she knows other au pairs who have gone through even worse. But she is hopeful this month's ruling will better protect au pairs.

“This is a huge profession that should be considered as any profession and get pay and all of the benefits as any other profession,” she said.

In addition to a wage bump, the state law now offers protections regarding overtime and work breaks. It also requires au pairs track their hours on a timesheet.

“It completely changes the dynamic. Like every minute now that we're spending together or that she's spending with the kids, it's like, is this time on the clock? We never thought like that before. Like, she was just our host daughter, we thought we were her host parents. That’s the nature of the relationship,” Mulvey said.

Scarpelli said after being here for three months, she finally feels settled in and doesn’t consider herself an employee.

“I mean, the first time I was like, ‘Oh, more money, less work,” she laughed. “But then I started to think. And that was like, okay, less work, less time with the kids. What am I going to do?”

In the meantime, hundreds of families across Massachusetts are scrambling for answers. It’s unclear, for example, if host parents need to pay unemployment insurance or if au pairs will be accountable for income and Social Security taxes.

Angela Spence of Newton, who has an au pair from Mexico, said that host families and au pairs across the state were blindsided by the court’s ruling and didn’t even know about the law or the lawsuit to begin with.

“Host families, who signed up for cultural exchange, now find themselves on the hook for $1,000 more per month or scrambling to find alternate childcare. Not to mention, the chaos of trying to navigate the massive conflicts between the state law and federal regulations,” Spence wrote in an email.

She said parents are organizing a family advocacy day at the State House on Jan. 8.

Cultural Care Au Pair, the Cambridge-based agency, told WGBH News it’s working with Healey’s office and other state agencies to help families get answers.

“As we help host families obtain clarification on the questions left unanswered by the court’s ruling, we will continue to explore legislative or regulatory changes that could provide some relief to host families from financial or administrative aspects of the laws. We will also be seeking an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court to reverse this ruling,” Natalie Jordan, a senior vice president of the agency, wrote in an email.

Mulvey said he and his wife understand that they’re privileged to have Scarpelli in their home, but that she will likely be their last au pair. With hundreds of thousands of dollars in graduate school debt and a mortgage, he said they’ll have to figure something else out for childcare next year.

“But what about everybody else?" Mulvey said. "When childcare costs are so spectacularly out of control, housing costs are so out of control, and people are getting out of undergrad with hundreds of thousands of debt, I don’t see how it’s sustainable for society.”