A long-awaited outing with her 9-year-old daughter to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts last April was cut short when Kimberly O’Connor received a call from her husband: a sheriff had delivered a “no fault” eviction notice.

It was a “no fault” eviction because the family — who had lived in the same three-bedroom apartment in Weymouth for 14 years — had done nothing wrong.

“Now I don't know who people think are, like you know, [who] get evicted or face homelessness,” O’Connor said. “But I always paid my rent on time.”

The landlord declined repeated requests for comment but, according to O’Connor, six days after getting the eviction notice, she received a text explaining that the apartment was being renovated and then the rent would go up by nearly 60%. She couldn’t afford the rent hike or, she soon discovered, the price of apartments across her city. The eviction notice gave her family just 30 days to find a new place to live.

“The uncertainty,” said O’Connor, “It's just such a scary feeling — potential homelessness and not knowing what’s going to happen next.”

O’Connor has worked as a preschool teacher in Weymouth for nearly two decades. Just 15 miles south of Boston, with access to highways and beaches, Weymouth has drawn growing numbers of people on the hunt for lower-cost housing and rents have shot up. According to

Zumper,

over the past year the average rent for a 3-bedroom apartment increased more than 50%. As a result, people like O’Connor are struggling to stay in the communities they serve.

Tremendous need for emergency housing

The volume of requests for emergency housing help is “tremendous,” according to Sue Keenan, director of housing and properties at the regional nonprofit Quincy Community Action Programs (QCAP).

“We are seeing more and more people who have never had to reach out to social services before, people who are employed, maybe they’re underemployed, or there was a break in the employment,” Keenan said. “So we’re seeing more people now like Kimberly.”

Keenan has spent three decades helping people in housing crises, and putting together the puzzle pieces of state or local assistance. She said she’s seen a recent rise in filings of “no fault” evictions, like in O’Connor’s case.

“They [landlords] want possession of their units back, and they either want it for family or they want to rehab them so they can rent them for twice as much as they’re renting for now,” Keenan said. “Or they want to sell them and they want them empty because it’s easier to sell that way.”

According to MassLandlords, “no fault” evictions across the state have averaged roughly 19% of total evictions since the start of the year. The group doesn't break down that data by community, but Executive Director Doug Quattrochi said it’s a “common situation” where there’s old housing stock like Greater Boston and tenants can’t stay when major renovations are needed.

“You would expect to see these no-fault eviction rates increase,” said Quattrochi. “A lot of people get stuck, the landlord loses their patience and now they’re filing in court because they don’t want to wait any longer.”

Keenan thinks spiking rents are partly the aftermath of the state’s request to private landlords to refrain from raising rents during the pandemic.

“Now that that’s over, everyone just feels like, ‘Oh, I got to get my money back, I got to recoup,’ and the rents are just going crazy,” she said.

Too rich and too poor

QCAP prioritized O’Connor’s case because she faced eviction.

“The first thing I was told was: do not leave your apartment until you have someplace else to go. Do not make yourself voluntarily homeless,” O’Connor said.

But as O’Connor began her hunt, she immediately found “very, very long” waiting lists for affordable housing, recalling one available unit that had 10 families already on the waitlist. Experts like Keenan said those apartments often become vacant only when tenants die.

"The first thing I was told was: do not leave your apartment until you have someplace else to go. Do not make yourself voluntarily homeless."Kimberly O’Connor, Weymouth preschool teacher

Between O’Connor and her husband, who’s training for a new job, the couple made around $70,000 before taxes. They earn too much for public housing but not enough to afford market-rate rent in Weymouth without help. The family falls in a middle ground that’s covered by “affordable housing.”

By law,

10 percent

of housing stock in Massachusetts cities and towns must be

affordable

to those with low to moderate income. But only about 7 percent of Weymouth’s housing is considered affordable — the balance of their requirement is currently filled by land “set aside” for future affordable housing, according to Weymouth Planning Director Robert Luongo.

Soaring rents, welcome investment

Lisa Belmarsh, a Weymouth city councilor who is on a committee overseeing Weymouth’s Housing Authority, worries about the impact of rising rents on the city’s current residents.

“I want people to stay in Weymouth,” Belmarsh said. “We are a community that really wants a wide, diverse group of people ... and I don’t want to see them forced out because they can’t afford to be here.”

Weymouth has increasingly drawn people from neighboring Quincy seeking more affordable rents.

“We have some of the conveniences of Quincy without that rent being as high,” said Luongo, the planning director. ”So that’s driving the market in Weymouth as well.”

Like many municipalities, Weymouth has also had a boom in new luxury apartment buildings over the past four years, which Keenan said is “fueling soaring rents.” But there’s a flip side; in Weymouth, those developments have also helped the city fill its tax coffers. Luongo said the revenue from developers has helped build a new library, a state-of-the-art middle school and renovate several parks.

“The quality of life is gone up in Weymouth, the streets are cleaner the sidewalks are being improved,“ Luongo said. "This growth and revenue from this development has tremendously helped the town stabilize its tax base.”

"It's going to run me about $625 more a month for less space. But it's the best I could find and the best I could do."Kimberly O’Connor, Weymouth preschool teacher

More money for less space

With time running out, O’Connor scrambled for the “cheapest option” she could find in Weymouth: a market-rate, two-bedroom apartment. With QCAP funding the first month’s rent and security deposit, O’Connor was approved. Then she cobbled together another $1,970 for a key deposit and last month’s rent.

“It’s going to run me about $625 more a month for less space. But it’s the best I could find and the best I could do,” O’Connor said. “I don't know what anything is going to look like for me. I'm just going to try to do the best I can day by day.”

With a teenage son who is on the autism spectrum and needs space, and a 9-year-old daughter, O’Connor had to decide who gets the two bedrooms and who will sleep on the couch. Daughter Tessa had to leave behind her beloved bunk bed and, because the new apartment is in a different district, will change schools.

“I feel like the stress and the tenseness from me is affecting her a little bit. She did express some sadness,” O’Connor said.

The family moved into their new apartment in early July. O’Connor is trying to be hopeful but worries about the future. She wonders whether she and her husband will run into trouble making the monthly rent, and whether she should get a part-time job. She also fears what could happen when her lease comes up for renewal, knowing how much rents spiked this year.

Still, standing in her new kitchen, O’Connor said she feels she’s had a reprieve from eviction and the domino effect of disaster she envisioned in not having a home. “I just feel lucky that my family has a roof over their head for the next 12 months.”

Stand up and help others

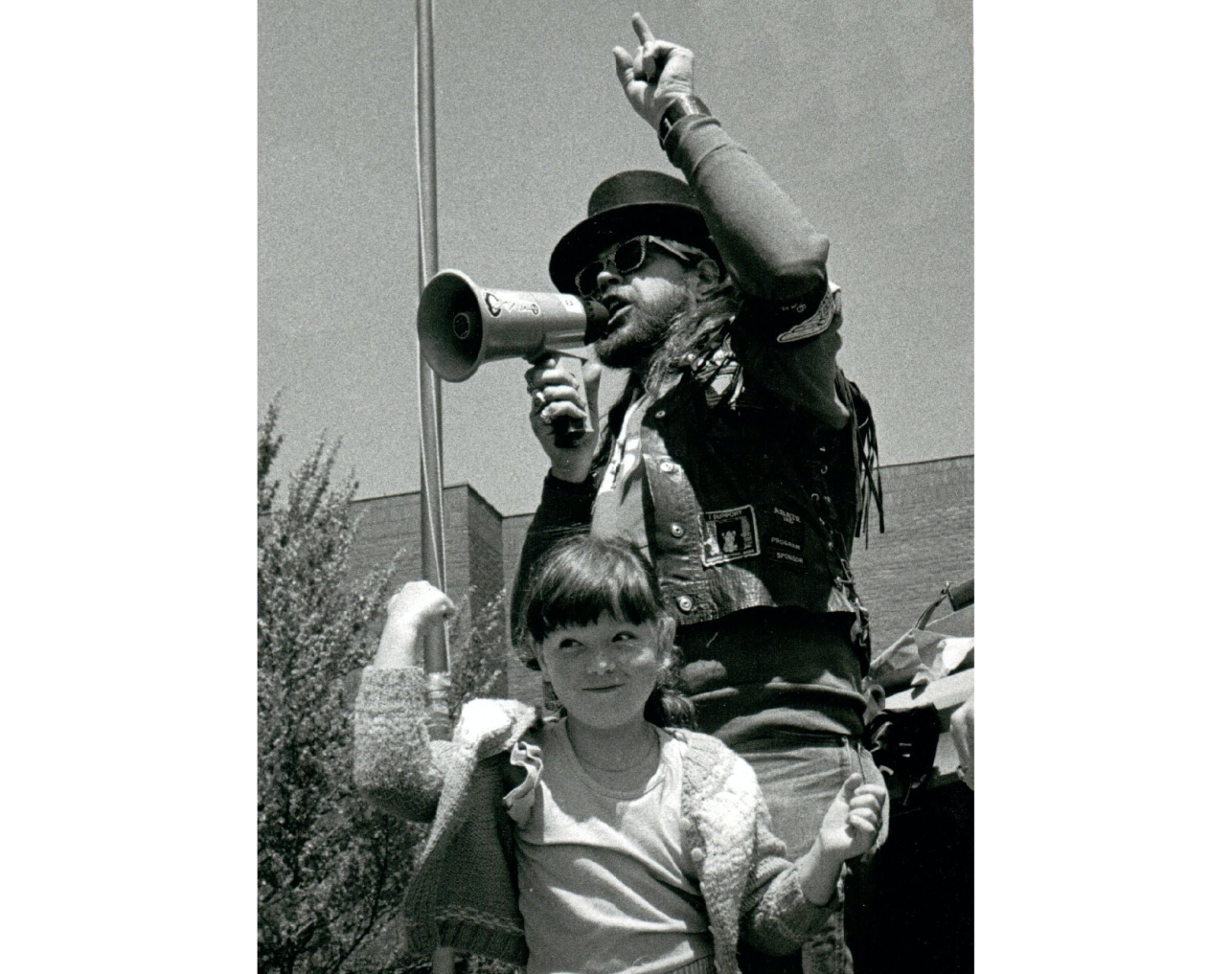

O’Connor traced her inspiration to go public with her housing struggles to her late father, an avid motorcyclist and an activist for the motorcycling community. He’d sometimes bring O’Connor along with him to the State House to lobby for helmet laws.

“My father influenced me to stand up for myself and others,” O’Connor said. “Like, tell your story. Don’t be ashamed of it. And just help others if you can.”

After GBH News published the first story in the series Priced Out: The fight for housing in Massachusetts , O’Connor emailed to share her experience.

“I just I feel like I want people to know they're not alone. I think that it’s important that, you know, who is struggling with this housing crisis might be your child’s teacher,” wrote O’Connor.

You can share your Priced Out story or ask a question you’d like answered by filling out this Google form . Find more from the series at Priced Out: The fight for housing in Massachusetts.

Correction: A previous version of this article included an incorrect year in the caption of the protest photo.