In a sterile triage room in Boston, a nurse offered Yannira Castillo condolences on losing her baby. Castillo looked at her husband and her mother with panicked eyes as she felt her composure disintegrate.

Soon, a doctor appeared at the side of her hospital gurney and made a promise. He took her hand in his, and Castillo remembers him saying: “‘You’re going to be okay. Your baby is going to be okay.’”

Castillo was nearly 24 weeks pregnant, still in her second trimester. The fetus was teetering on the edge of viability, and her body was inexplicably delivering it. The contractions were coming with a force and fury that frightened her. She prayed as hard as she knew how.

Caught between the nurse’s condolences and the doctor’s assurances, Castillo had no idea why she had gone into labor or what to do about it. Neither did the medical profession.

“Every time I’m asked by a patient, ‘why did this happen?’ My answer is typically, ‘we don’t know.’ And I’m tired of having to answer, ‘we don’t know,’” said George Saade, the chief of obstetrics at the University of Texas Medical Branch and the former president of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, the professional organization for obstetricians who specialize in high-risk pregnancies.

One in 10 babies is born preterm; that is, more than three weeks before the baby’s due date. And, despite the anguish hundreds of thousands of families go through each year — and the billions of dollars it takes to care for the children — little is known about what causes premature births or how to prevent them.

The best care that medicine has to offer women like Castillo relies on techniques that are sometimes more than a century old. The result is that many preterm births are unexpected and unexplained. At a time when medicine is creating technologies to edit human genes and developing highly effective COVID vaccines in under a year, the lack of investment in maternal care has doctors in the field sounding the alarm.

The cost of knowing so little is enormous. Medical bills for people who are born preterm total $17 billion each year, and much of that cost is borne by Medicaid, the taxpayer-funded program that covers nearly half of all births in the United States. Once economists add the medical care of the mother, the price tag of special education that some preterm children require, and lost wages and productivity for the preemies who have disabilities lasting into adulthood, the annual cost swells to $25 billion . But the economists behind that figure say it’s an underestimate; the real number could be twice as much, or more.

"We are worse than any other field of medicine, and yet we're left alone to flounder."George Saade

Saade says it doesn’t have to be this way. He blames the staggering cost on a severe lack of research and investment in prematurity, estimating that maternal care is a century behind the rest of medicine. He is one of a growing number of obstetricians and medical experts who say the field is neglected by society — and failing patients as a result.

“We have an urgent crisis,” said Rahul Gupta when he was the chief medical and health officer at the March of Dimes, the leading nonprofit focused on maternal and infant health. “It’s almost a perfect storm what’s happening, and it’s literally ignored.”

“There is no doubt that premature birth is the most important problem facing obstetrics today,” said Roberto Romero, who runs the National Institutes of Health, or NIH’s, research branch that studies pregnancy. “The consequences of premature birth can last a lifetime.”

“We are worse than any other field of medicine, and yet we’re left alone to flounder,” Saade said.

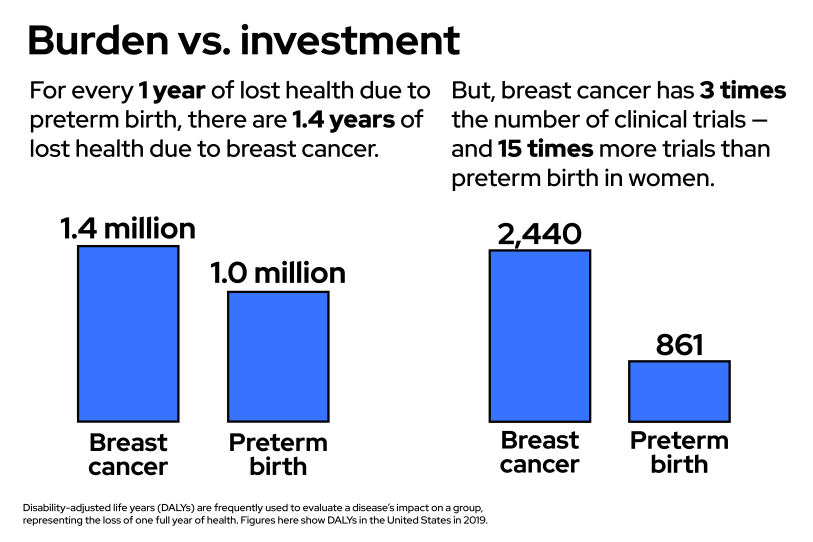

A GBH News analysis found that clinical trials aimed at preventing preterm births lag far behind trials aimed at other conditions. In the United States since 2000, there have been more drug trials for erectile dysfunction than for prematurity in pregnant women. There are 15 times the number of clinical trials about breast cancer than about preterm birth in women. Finally, our analysis found, there are more than double the number of clinical trials about infertility — helping women get pregnant — than about preterm birth — helping women stay pregnant.

Experts at the forefront of calling for change have pinpointed the barriers that keep obstetrics a century behind. They say progress in preventing preterm births is possible, but it will take a diverse cast of characters — from lawmakers to drug companies and social activists — to make it happen.

‘The Last Frontier’

Castillo spent a decade fearing a preterm delivery. Two of her older children had been born early: They never made it to their 40-week due dates, or even the 37-week finish line that would designate them ‘full term.’ Instead, they were born at 32 weeks and 29 weeks, each spending time in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, or NICU, before coming home. While Castillo wanted another child, she worried she would have another preterm baby — another so-called “preemie.”

Castillo and her husband eventually pushed their anxiety aside and got pregnant again. Castillo remembers telling her doctor: “Whatever you have to do to keep this baby in, just do it.”

Every Friday she got injections of synthetic progesterone.

She got a cerclage, a surgery to stitch her birth canal closed.

When she felt pain in her lower back, Castillo said, her doctor gave her an order: “‘You have to stop working, and you need to do bedrest.’” She stayed in bed and frantically Googled to find something that might help.

But, at just 23 weeks into her pregnancy, the pain morphed into contractions. At the hospital, she was given magnesium sulfate to stop labor. But, she says, it didn’t work. Months shy of a full-term pregnancy and despite the medical interventions, Castillo’s son — Matteo — was born a few minutes after midnight at exactly 24 weeks of gestation. Matteo’s due date had been at the end of June. He arrived on an overcast day in mid-March.

It was clear from Matteo’s first cries that the nurse’s condolences had been a mistake. But, pediatricians say, it can take years to know whether preemies born at that stage will “be okay,” as Castillo’s doctor had promised.

When he was born, Matteo weighed just one pound, nine ounces. His hand couldn’t close around his mom’s pinky. “My pinky was so big, and his hand was just so, so tiny. So skinny. My god …” Castillo remembered, her voice trailing off.

Babies born as early as Matteo cannot breathe on their own. They cannot eat on their own. They cannot regulate their own body temperature. Their brains are still largely smooth, having not yet developed all the natural grooves and folds. Their skin is translucent. Their eyes are fused shut.

Castillo quit her job.

She spent 116 long days with Matteo in the NICU. Holding him on her chest for long stretches, Castillo tried to create a sense of calm amid the hospital hubbub. She says she kept wondering how medicine was able to keep this fragile baby alive, but it couldn’t keep him from being delivered early.

To this day, Castillo said, “they never knew what was going on with me.”

As with most spontaneous preterm deliveries, doctors have guesses: Maybe it was an infection. Could her progesterone levels have been too low? Perhaps it was a condition inelegantly called an “incompetent cervix.” Or it could have been a half-dozen other things.

Clinicians are often unable to determine the culprit. And so, they try all the interventions available, even if they’re outdated and it’s unclear if they work.

That’s what happened to Castillo.

“We keep reusing the same ideas. There has not been innovation. There have been really no new therapeutics,” said Michal Elovitz, a professor and high-risk obstetrician at the University of Pennsylvania, adding that the interventions that do exist often fail to prevent or treat preterm labor. “It’s egregious.”

"They never knew what was going on with me."Yannira Castillo

Progesterone occurs naturally in the body and is known to keep the uterus quiet, to keep it from contracting. For 50 years, clinicians have given women additional progesterone in the hopes of fending off a miscarriage or preterm birth. But there’s a vigorous debate in the medical community about whether the injections of synthetic progesterone that Castillo received actually work. The Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research suggested withdrawing the drug from the market, while The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends it as “the only treatment currently available.”

The first cerclage to sew shut the cervix was performed in the 1950s, but — even today — it’s hard to figure out who the procedure helps and who it doesn’t.

Bedrest has been around for hundreds of years, but there’s “absolutely no evidence for bedrest,” said Elovitz. It’s on par with the recommendation Castillo found while desperately Googling: sleep with your legs elevated.

And the magnesium sulfate that Castillo received when she was already in labor? It has been used to try and stop contractions for a century, but “it’s not been shown to prevent preterm birth more than 48 hours,” Elovitz said. That short window is hopefully just long enough to give the fetus steroids, which can improve a preemie’s outcomes , including helping their underdeveloped lungs mature more quickly.

“Every few weeks you get a publication that revolutionizes the way we treat some condition in other fields of medicine. We don’t see that in pregnancy,” said Saade. “Women’s health is the last frontier.”

A Stubborn Problem and Its Consequences

While there haven’t been advances in preventing preterm births, there has been extraordinary progress in caring for preemies when they do arrive early.

“We’ve seen this pretty dramatic reduction in the risk that a preterm baby is going to die,” said Paul Wise, co-director of Stanford’s Prematurity Research Center. “However, the risk that a baby is going to be born prematurely in the first place has been stubborn. It hasn’t gone down.”

Many people trace the improvements in preemie care back to late fall 1963.

That’s when the world held its breath for 39 hours after First Lady Jackie Kennedy gave birth to a son five and a half weeks early. He was airlifted from Cape Cod to Boston and doctors desperately tried to save him, but they failed. Patrick Bouvier Kennedy’s short life had a big impact. There was suddenly an investment in preemie research, an infusion of resources, a sense of urgency. Soon, NICUs were proliferating. And it wasn’t long before a medical specialty was created to care for preemies and other newborns.

Fast forward a half century to 2017. Kristi Magida was just 23 weeks pregnant — 17 weeks before her due date — when her water broke. She knew it was serious when the nurse at her obstetrician’s office told her to call her husband. Magida rushed by ambulance to a hospital in Boston where their daughter, Becca, was born. Weighing one pound, seven ounces, Becca was whisked off to the NICU. The smallest preemie diapers the hospital had were about the size of a credit card, yet they were far too big. After nearly eight months in the hospital, Becca made it home.

“Pretty much the whole world stopped for the first year,” Magida said. “I don’t remember thinking about anything except how to keep that kid alive.”

In the NICU, Becca was covered with wires and machines, surrounded by a chorus of beeps and buzzes. The list of possible complications is long, and the earlier the infant is born, the longer the list. Preemies are more likely to experience bleeding in the brain, scarring in the lungs, holes in the heart, infections in the intestines, vision loss and hearing loss, among other challenges. And, as the infants grow into children, they are more likely to have autism, attention deficit disorder, intellectual disabilities and learning disabilities.

The NICU team helped Becca through multiple bouts of pneumonia. Doctors fixed a vessel in her heart. Becca got a tracheotomy to help her breathe, and a feeding tube to help her eat.

At age four, Becca is now in preschool. She loves outer space and cooking. She’s learning to read and write. But her path is still bumpy. While her tracheotomy and feed tubes were removed about a year ago, she has partial paralysis of her vocal cords, and her speech is severely delayed.

“She was nearly three before she said the word ‘mommy,’” said Magida. “That’s a big reminder that she’s been through a lot.”

While NICU care can be remarkably effective, it can also be remarkably expensive. Economists say the newfound ability to save ‘extremely premature’ babies — or those born before 28 weeks of gestation — contributes substantially to the cost of prematurity to society. In just the first few months, medical bills for the earliest preemies are regularly hundreds of thousands of dollars, sometimes over a million.

But the consequences are more than just a dollar figure.

“The unfortunate reality is that even babies that end up in the NICU and receive that excellent treatment can still end up having lifelong health challenges,” said Stacey Stewart, current president and CEO of the March of Dimes. Eighty percent of babies born at Becca’s gestation have at least one severe disability in adulthood, including intellectual disabilities and autism.

And it’s not just the preemie. It’s the mother’s health, too. After a preterm birth, women are at higher risk for their own medical issues later in life. For example, Elovitz said, a woman who had preterm preeclampsia, or high blood pressure — which can trigger an early delivery — is at the same risk of cardiovascular disease as an active smoker. And, Elovitz added, “that risk never goes away.”

Prematurity is “one of the most impactful conditions that we know of,” said Saade.

That impact is not evenly distributed. There are nearly 400,000 premature babies born in the United States every year. Within that group, there are “significant, persistent, and very troubling” disparities, according to Richard Behrman and Adrienne Stith Butler, who wrote a report on prematurity for what was then the Institute of Medicine. The chance of an African American baby being born prematurely is almost 50% higher than the chance for a white baby, and that number climbs even higher for extremely premature infants.

While researchers have worked to tabulate the medical toll and the economic cost — and who bears the brunt of those burdens — the emotional consequences of prematurity are sometimes left undiscussed. “It’s traumatic,” said Elovitz. “Preterm birth is one of the most untenable burdens that women have to deal with.”

Allie Hershey knows firsthand. After undergoing fertility treatment in order to conceive, Hershey and her husband were elated to discover they’d more than succeeded: they were pregnant with twins.

But one Saturday morning, midway through her pregnancy, Hershey was driving home from a haircut when she knew something was wrong. She rushed to their home and, soon, she was on the bathroom floor delivering the twins.

“They were alive and breathing and crying,” Hershey remembered. “And, in that moment you think, ‘Well, maybe, maybe this won’t be horrific.’”

But she was only 21 weeks along, just past the halfway mark of her pregnancy and just shy of the viability threshold. The twins lived only a few hours. Hershey and her husband received their death certificates along with their birth certificates.

A little over a year later, the Hersheys had a little boy named Emmett. He was also born early, but he was further along, at 32 weeks. After nearly two months in the NICU, Emmett came home. Now, each night when the Hersheys tuck him into bed, they tell him the twins — Caleb and Gabriel — are keeping him safe.

Hershey says she never knows exactly when she’ll be flooded with emotions about the twins. It’s taken years to slowly release the feelings of guilt: What if I’d called my doctor earlier? And the unanswered questions still nag her: Why me? What caused this?

She’s far from the only parent facing the fallout of preterm birth. Prematurity is a leading cause of infant mortality in the United States: of the roughly 20,000 children who die each year before their first birthday, two in three are born preterm.

“That’s a lot of dead infants. A lot of infants who miss the opportunity to grow up and contribute to society,” said Scott Grosse, a health economist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Experts say the medical, financial and emotional consequences all point to one answer: invest in prevention. But that has not happened. A GBH News analysis found, in the past 20 years in the United States, that for every four clinical trials that focus on helping preemies once they are born, there is just one clinical trial focused on preterm birth in the mother. “Neonatal studies,” or studies on newborns, “are much simpler, easier and less costly,” said Saade.

The lack of research about pregnancy and preterm labor means many of the basics remain unknown. How does labor even start, whether preterm or at term? How it is that the cervix can disappear during delivery and then reappear in minutes? How exactly does the placenta function? Obstetricians have guesses, but not answers. And, while researchers have identified a long list of risk factors — from wildfire smoke exposure to maternal age to a previous early delivery — they do not know how these risk factors work together to actually trigger early labor.

“This is far more complex than anything else we do in medicine,” said Romero, of the NIH.

Unlike the rest of medicine, in pregnancy, there are two patients instead of one: the mother and the fetus. And they can have incompatible needs. Unlike many other diseases, which can develop over years or decades, the window in pregnancy to identify who is at risk and address it is short. “Everything is compressed into a few weeks,” Romero said.

Further, a whole host of things can cause prematurity, whereas many other medical conditions can be traced to a clearer root cause. And, while much of medicine can turn to lab animals for hints, that doesn’t work well in prematurity research. “Rats, mice, guinea pigs, sheep, even non-human primates…these models don’t have preterm births,” said Saade.

Stewart, of the March of Dimes, said our lack of knowledge is costly: “If we’re not going to invest on the front end, we have to expect that we’re going to pay dearly on the back end, and that’s what we’re doing.”

Three Hurdles

When obstetricians lament the shortcomings of their field and the poverty of options for addressing prematurity, their focus turns to three major hurdles that stand in the way of more research: insufficient funding, fear of studying pregnant people, and drug companies that are hesitant to invest.

The first challenge is that there is not enough research funding on pregnancy care and preventing prematurity. “This is not a priority for the NIH or other institutes who can actually move the needle forward,” said Elovitz.

The National Institutes of Health is the largest funder worldwide of basic and clinical biomedical research. Nestled under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the NIH has an institute dedicated to the eye, to aging, to cancer, to dental issues, to alcoholism, to drug abuse, to neurological disorders and strokes — and 14 others . Yet, Elovitz pointed out, there is no institute specifically dedicated to researching women’s health.

Research on reproduction falls under the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, or NICHD. The result, Elovitz said, is the study of maternal health and pregnancy competes against a litany of childhood issues for limited funding.

In a statement, a NICHD spokesperson said issues of maternal and pregnancy health are prioritized and that they “work within the budget allocated by Congress.” In 2020, the NIH spent roughly 1.3% of its budget — or $550 million — on pregnancy research and about 1.1% of its budget — or $444 million — on preterm birth, low birth weight and newborn health research. In contrast, the NIH spends about 7% of its budget — or $3 billion — on HIV/AIDS research, which has around 35,000 new infections in the United States each year, compared to nearly 400,000 preterm births. The NIH does have an Office of Research on Women’s Health but, unlike an NIH institute, it does not do or fund research. Instead, it is tasked with advocating for and facilitating research.

The second factor at play is “a literally unhealthy reluctance to include pregnant women in clinical trials,” according to Alan Guttmacher, a former NICHD director. There is a long history of viewing medical research on pregnant women as too risky, too potentially harmful.

A small number of tragedies contributed to this hesitation — like when, in the 1950s and early ’60s, thalidomide was prescribed for morning sickness, but caused birth defects. The federal government cemented this mindset when it categorized pregnant women as a ‘vulnerable’ group in need of added protections in clinical research, said Anne Drapkin Lyerly, an obstetrician and bioethicist at the University of North Carolina. Pregnant women were categorized as vulnerable alongside children, prisoners and people with intellectual disabilities, despite being able to give their own consent. That designation was removed in 2017, though the change didn’t go into effect for more than a year, but Lyerly says it scared off researchers: studying pregnant women came to be seen as not only complicated but “ethically suspect.”

Efforts to protect pregnant women from medical research — rather than through medical research — ultimately means there is limited scientific evidence to guide their care. Despite recent efforts to address the knowledge gap, the reality is still that many drugs used during pregnancy have never been properly studied in pregnant people. That leaves doctors grappling with an array of questions without good answers: Does this drug work? Is it safe? Does it cross the placenta to the fetus? How do you know the right dose when a woman's kidneys, which can filter out drugs, are working overtime during pregnancy?

Such questions matter more when pregnancy becomes highly medicalized, as it often does for those at risk of preterm birth. But the lack of scientific evidence affects almost all pregnant people. Half of pregnant women take at least one prescription drug at some point during their pregnancy and, when over-the-counter drugs are included, that figure shoots up to over 90% . At the same time, 98% of all drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration since 2000 do not have sufficient data to know whether or not they pose a risk to a fetus.

“In pregnancy, there is a profound dearth of evidence to guide care,” said Lyerly. “The impact has been a mix of medical harm and uncertainty.”

The third big hurdle, experts say, is that what knowledge we do have isn’t being turned into new therapeutics. It is typically the private sector — particularly drug companies — that take on this complex and costly task. Without this final piece, Saade said, any other research is “almost wasted.”

The primary deterrent for industry? “It’s largely the fear of a lawsuit,” said Bob Ward, a retired neonatologist and professor emeritus at the University of Utah, who has consulted for drug companies. He says pharmaceutical companies have been burned by trials in which a persuasive lawyer and a sympathetic jury blame an unrelated malformation, like a cleft lip, on a medication used in pregnancy. In the end, the drug company pays millions.

Ward said, from their perspective, it’s just not worth getting involved in prematurity compared to other more lucrative and less risky areas of medicine. Returning to an earlier example, GBH News found that, over the past two decades, there have been more drug trials nationally to address erectile dysfunction than to address preterm birth in women — and yet, erectile dysfunction has attracted four times more industry-funded drug trials.

Numerous drug companies, including Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lilly and Novartis, declined interviews. However, representatives from Ferring Pharmaceuticals wrote an article in 2021 acknowledging that the pipeline for new therapeutics in obstetrics “looks bleak.” They point to the other hurdles — “scientific and ethical complexities” as well as liabilities — to explain why “obstetrics is seriously left behind.”

‘Willing to Think Big’

Experts say that, in order to solve a problem like prematurity, research will need to go from neglected to prioritized. But, they say, it’s possible. Researchers look to two models from elsewhere in medicine — cancer and pediatrics — for how funding has been allocated, research has been facilitated and drug companies have been incentivized.

“We’ve had so far two cancer moonshots, right — two! Nixon and Obama. Have we had a pregnancy moonshot? No,” said Saade.

The data agrees with Saade. In 2020, the NIH put more than $7 billion dollars — 16% of its budget — toward cancer research, and nonprofits spent billions more. As the GBH News analysis found, in the last two decades in the United States, there have been 15 times more clinical trials about breast cancer than about prematurity in women. Even after adding in all the trials on prematurity that focus on the children, breast cancer still has almost three times as many clinical trials. But, in the United States, the conditions exact a similar toll on society. Researchers quantify the burden a disease takes by measuring the number of years lost to disease, disability and early death, and when considered alongside a whole slew of other conditions, breast cancer and prematurity end up being close neighbors. Yet, breast cancer, and cancer more generally, receives far more attention and resources.

But it hasn’t always been that way.

“People wouldn’t even use the word cancer. If they mentioned it, they whispered: ‘The big C,’” said Claire Pomeroy, president of the Lasker Foundation, a nonprofit aimed at encouraging medical research.

Throughout the first half of the 1900s, cancer was seen as incurable and shameful, but it started to come out of the shadows in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. This was no accident; it was a conscious and concerted effort. A driving force behind this change was a woman named Mary Lasker.

“She was relentless,” said Pomeroy. “She understood that this was a big problem and the solutions needed to be big, but Mary was willing to think big.”

Mary Lasker fought her battle on two fronts. First, she set out to get the public on board. She did things like make sure the word ‘cancer’ could be said on the radio — which hadn’t been allowed — and convince the Ask Ann Landers advice column to write about the need for cancer research. Next, she turned her eye to government funding for research. She spent decades lobbying politicians with the rallying cry: If you think research is expensive, try disease. She won a Presidential Medal of Freedom and a Congressional Gold Medal for her activism, but perhaps the best reward was President Nixon signing the National Cancer Act of 1971.

Speaking at the signing ceremony, Nixon said: “Everything that can be done by government, everything that can be done by voluntary agencies, in this great, powerful, rich country now will be done.”

With an injection of research funding and far more public awareness, cancer prevention, detection and treatment has been transformed. For example, widespread pap smears and mammograms have meant cervical cancer has seen a 71% drop in mortality since 1969 and breast cancer mortality has dropped by 40% since 1989.

“Cancer research has shown us what can be done,” said Elovitz. “We need to be brave. We need to be bold.” In other words, there needs to be a Mary Lasker of prematurity.

Yet, scientists and clinicians acknowledge that, in important ways, understanding and preventing preterm birth may be more complicated than fighting cancer. There’s both the reluctance to testing new treatments during pregnancy and the hesitancy from big pharma. But, experts argue, these challenges can be overcome: just look at advances in pediatric medications in the past 20 years.

“Children were being completely left out. People maintained that it was unethical to test drugs in children, that they were too delicate,” said Ward, the retired neonatologist. Historically, drug companies also steered clear of pediatrics, seeing little financial upside to developing new therapeutics for this demographic. “The market for medications in children is tiny,” said Ward, who also served as chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Drugs and pushed for legislative intervention.

And a couple of bipartisan laws — one in the 1990s and one in the 2000s — changed the landscape. One law essentially offered pharmaceutical companies a financial incentive if they studied their drugs in children. The other law required new drugs to be tested in children if the disorder was likely to occur in children. And for all the drugs already on the market, the NIH stepped in to facilitate the research that was needed.

“We have seen a dramatic increase in the study of drugs in children and, for pediatrics as a group, about 50% of the drugs now approved have been studied and labeled for children,” said Ward. Before the legislation passed, he estimated, 90% of drugs used in children were not studied in children.

“Pediatric clinical trials participation has evolved from ‘not ethical’ to ‘not ethical not to.’ The same will hopefully occur in obstetrics,” write Zhaoxia Ren and Anne Zajicek, two physicians at the NIH.

A Nightmare and a Miracle

Matteo Castillo was nearly four months old when, on July 4th, he left the hospital for the first time. Yannira Castillo said the freedom to take her child home felt wonderful and terrifying. She barely slept at first, staying up to make sure Matteo remembered to breathe, something for which he often needed help while in the NICU.

The hospital had given Castillo and her husband strict instructions to keep Matteo close to home. He needed time to grow and strengthen without the burden of battling germs from the outside world. “We didn’t go out at all,” said Castillo. “We stayed home for the first two years of his life.”

During those early years, there were failed hearing tests and classes on how to help Matteo learn to eat. Pediatric physical therapists and speech therapists visited the house. Castillo, her husband and their older children poured everything into Matteo. They knew the data: the majority of infants born at Matteo’s stage end up having at least one severe disability . They watched anxiously to see if Matteo would inch past the milestones that other kids cruised by. They watched to see if the doctor’s promise — “your baby is going to be okay” — would be fulfilled.

Now, Matteo is five years old and has just started kindergarten. Castillo says she still worries about all the stumbling blocks prematurity scatters along a child’s path, especially the ones that don’t surface immediately. She wonders about autism and attention deficit disorder. She frets about Matteo’s lungs, still checking on his breathing every night. But in the morning, when Matteo wakes up happy and eager to get to school, she quiets her worries and lets herself exhale, trusting that the nightmare has become a miracle.

She smiles to herself remembering an early fall day, a few weeks ago, when Matteo was outside his grandmother’s house in Chelsea, Mass. He spotted a little kid across the fence on the neighbor’s porch and, as the family watched from a distance, the two boys struck up an easy conversation. The young neighbor explained that he’d been born with only one leg. “And Matteo started telling the kid, ‘Oh, I was in the hospital when I was born, too. I had a lot of tubes in my face,’” recalled Castillo.

By almost any metric, Matteo has far surpassed ‘okay.’ He has thrived. But experts say that for Matteo Castillo, for Becca Magida, for Caleb and Gabriel Hershey, for Patrick Kennedy and for the nearly 400,000 preemies born each year, true success would be preventing premature births in the first place.

Editor’s note: This reporting project was undertaken with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 Data Fellowship. In the interest of full disclosure, author Gabrielle Emanuel’s son is among the 1 in 10 children born preterm.

Methodology: The GBH News data analysis focused on clinical trials, rather than observational studies or basic research, since experts indicated that clinical trials can lead directly to changes in patient care. We used the federal database at clinicaltrials.gov to compare the investment in prematurity research with the investment in other conditions. We limited the focus to trials that were conducted at least partially in the United States between 2000 and 2020; in 2000, the database was made public and many more studies were obligated to register. We ran a search for trials using the term “preterm birth” and the search engine automatically included related terms such as “premature,” “preterm,” “prematurity” and “early onset of delivery.” Next, we applied a filter under “recruitment” to exclude all incomplete trials (withdrawn, suspended, terminated). With the resulting database, we sorted results by age to see how many of the studies are focused on children (<18 years old) and how many focused on adult women. By a cursory review of the trials, it appeared the studies focused on adult women were often aimed at preventing prematurity during pregnancy, whereas the studies that focused on children were often aimed at treating premature children. The database was further sorted to see how many drug trials were conducted compared to other types of interventions, such as dietary supplements. The analysis also noted the funding source for each trial. Interventions that were at least partially funded by industry were marked as industry-funded. The same process was then used for a series of other medical conditions, including erectile dysfunction, breast cancer and infertility. This methodology was reviewed by several academics as well as an outside data journalist.