Part 2 of a two-part series. Click here to read or listen to Part 1.

“Gentlemen, how we doing?” says Principal Jennifer Police, greeting two boys as they walk down a quiet hallway at Monomoy Regional High School.

“Good,” they reply in chorus.

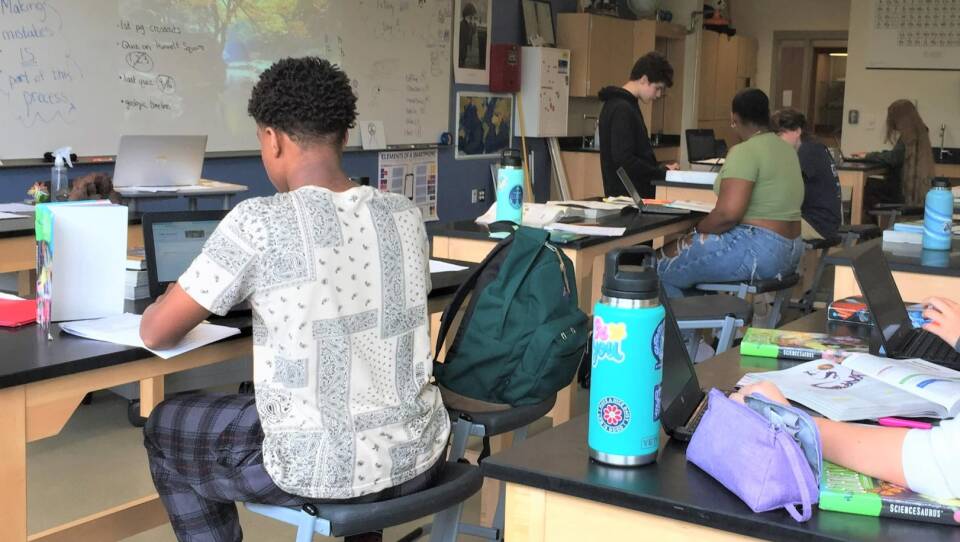

She makes her way through a video studio, engineering lab, and science classroom, talking about how things have changed since COVID-19. The conversation keeps coming back to digital technology — and especially, phones.

She says wants people to understand the world that young adults are navigating.

More Education

“Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat — these have all emerged, really, during the pandemic,” she says.

She says while those platforms existed before, students didn’t use them as extensively as they do now. “They communicate through social media apps. Kids don't really even text.”

Even before the pandemic, many adults thought students’ phone use was too much.

Then came remote school, extra screen time, and the burst in popularity of social video platform TikTok. Isolated at home, students became more immersed in technology, for both learning and socializing.

Further down the hall, we happen upon a “team room” — it’s an open area off the hallway, with study tables, like in a library.

Students can work together here with some level of autonomy. But right away, the principal notices — they’re on their phones.

She points.

“See? Cell phone. See? Cell phone. See? Look look look,” she says.

Initially, one student says they’re researching a final project. But when Police assures them they’re not in trouble, another student, soon-to-be sophomore Hailey, tells it like it is.

“I was scrolling on TikTok, and to be even more honest, when you walk away, I'm going to go back on my phone,” she says.

She says she sometimes uses the phone for schoolwork, but it’s also a distraction.

“I'll sit down and do homework, and then I'll pull out my phone, and I won't do my homework,” she says.

“You guys, like, lay in bed at night and do the incessant scrolling?” the principal asks knowingly.

“Yes.”

For better and worse

Since the pandemic began, students have become more addicted to their phones, even in middle school, said Michael Horton, principal of Cyrus Peirce Middle School on Nantucket.

“Unless parents are really supervising kids or taking their phones away from them, they have no idea when kids are going to bed at night,” he said. “And that's affecting their schoolwork and academics.”

And observers point out that, of course, it’s not just the kids; adults are living in this world, too.

But tech in the pandemic hasn’t been all bad.

Technologies that blossomed to facilitate remote learning are here to stay.

For one thing, Nantucket teachers have started using an electronic daily syllabus. Horton said students can review it to clarify what’s expected of them, or catch up on work they missed when they’re sick or off-island.

“So that's a kind of a huge improvement, I would say, in the organization of daily class lessons and the use of technology,” he said.

In some districts, parents use video calls to meet with teachers or to watch their child get an award when they can’t be there in person.

The web, worldwide

Students are still recovering from COVID isolation, but they’ve gained a more global mindset, said Denise Patmon, an associate professor of education at UMass Boston.

“I ask people to shift their position and not necessarily look at what damage the pandemic caused,” she said. But rather, “What did kids learn during the pandemic?”

“And the kids have amazing, amazing new information that I would have never even thought to ask.”

Some educators say students are still behind, because remote school didn’t measure up. And academic gaps made more obvious by the pandemic persist.

But we shouldn’t be talking about just catching up, Patmon said.

“Catch you up to what? To things that were relevant in 2019?” she said. “It's 2025, for all practical purposes. We’ve got to move forward.”

Both she and the Monomoy principal pointed out that kids can stream the war in Ukraine live — and Google the answer to just about any factual question.

So Principal Jennifer Police says while content is still important, it’s time, more than ever, to teach collaboration, problem solving, and critical thinking.

“What they don't need us for, anymore, is information,” she said. “Where can they access information? Online.”

“So our jobs, I think, as educators now, is to connect what you're learning in the classroom and then go see it in the real world. You need to see why — like, what's the purpose of algebra? I'm going to show you the purpose of algebra.”

The pandemic changed education for the long haul, the experts say — in some ways that are troubling, and others, exciting.