The Boston School Committee voted unanimously Wednesday to change its admissions policies for the city's exam schools, calling it a historic move that will make the three schools more diverse.

The decision overturned a system that has existed for two decades, a declared attempt to make the schools more diverse and better reflect the city's racial, geographic and economic realities.

"We have come to a place where we are ready to move this district forward," said School Committee chair Jeri Robinson.

Under the new policy, students' grades will be more important than their exam score. The district will issue invitations to students in socioeconomic tiers based on geography with a set number of seats for each.

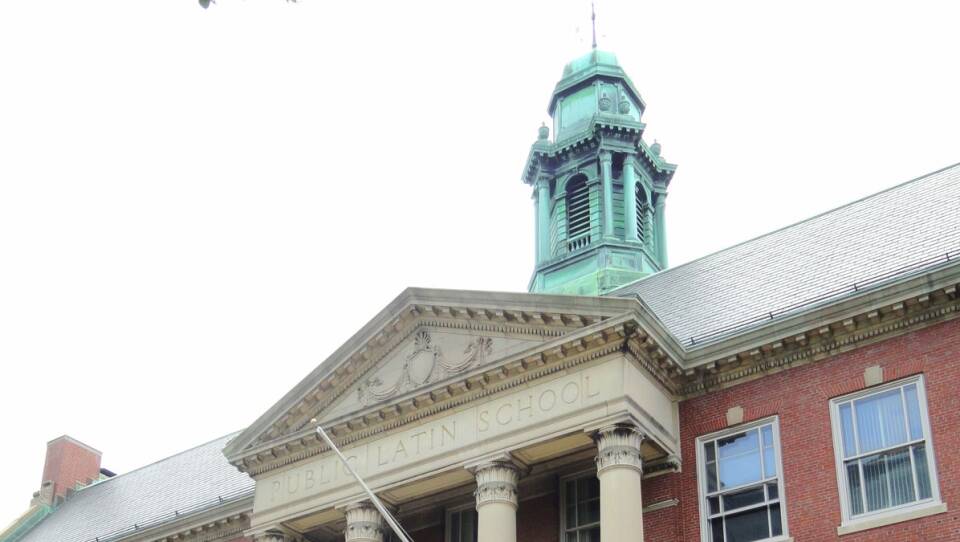

Critics had expressed concern that the changes could bring down the quality of the education at the exam schools, Boston Latin, Latin Academy and O'Bryant School of Mathematics and Science. They asked the committee to suspend voting until two vacant seats on the committee were filled.

After three hours of discussion and comment, as well as months of work by a task force that spent more than 60 hours examining the process, the committee voted 5-0 to make the change.

Committee member Ernani DeAraujo, recalling his own experience as an immigrant youth from Colombia whose mother worked three jobs, said attending Boston Latin presented a life-changing opportunity because of the skills and network it offers.

"For an immigrant kid, from poverty, it really is the American Dream," he said, adding that work still needs to be done to get more non-white students to apply to the schools.

"The intention of this plan is to ensure applicants with the best grades, the best test scores will have the best shot at choosing one of these schools," he said. It "could ensure that applicants are successful regardless of their socioeconomic backgrounds."

The process to reconsider the policy began about a year ago under a push from parents, students and activists who noted the exam schools are overwhelmingly white in a city where the majority of students are not. More than 70 percent of the students attending the city's schools are Black or Latino, while less than 15 percent are white. A 2018 Harvard study found that segregation in Boston schools continued and that highly-skilled Black and Hispanic students do not enroll in any of the three schools.

Superintendent Brenda Cassellius said equity has been a priority of her administration, calling the changes a "huge step forward for our students."

Some students, parents and activists had argued that a lottery system would be the most fair way to offer admissions.

Earlier this year, a 13-member task force began the months-long process of making a recommendation designed to make admissions more fair. At the last minute, the group faced pressure to carve out an exception that would allow more white students to gain admission at the expense of disadvantaged youth with high qualifications.

That change would have allowed 20 percent of invitations to the schools to be sent to students based on their grades and test scores citywide — instead of by socioeconomic tier.

The 20 percent carveout was not part of the superintendent's recommendation to the committee. Cassellius said a review of the data showed only minor differences between a proposal that offered 80 percent of seats by socioeconomic tiers and her recommendation of 100 percent of invitations to be issued to students in that manner.

To gain entrance, students must have a B average or higher. A composite score for each student will be a combination of their admissions test score (30 percent) weight and their grades (70 percent). In the past, each carried equal weight. Students attending a high poverty school where 40 percent or more of students are economically disadvantaged would receive 10 additional points to their score, with students who are in foster care, public housing or homeless receiving an additional five points.

Cassellius urged committee members to take a vote, noting that holding out for a perfect solution could "potentially lose this moment."

"My personal position, every student should have equal opportunity to access," she said. "It's who I am. It's how I lead. It's what drives me to do this work even on difficult days."

Noting how desegregation efforts in Boston have been unsuccessful for decades, school committee member Quoc Tran sounded an optimistic note that the plan would move the city forward.

"We've been talking about different categories, different factors that affect certain groups of people," Tran said. "And those factors are real, are prevalent and are here today, until now."

Editor's note: This story has been updated to clarify that the new policy considers a high poverty school one in which 40 percent or more of students are economically disadvantaged, rather than more than half.