This year, 161 students who are new to the United States joined the Somerville school district — and the vast majority of them do not speak English as their first language, which presents an added challenge for schools returning from a pandemic year.

School counselors, social workers and psychologists said having kids back in school buildings after remote learning is a step forward for addressing their mental health needs, especially those from immigrant families. But a shortage of multilingual school counselors and stigma around mental health makes it difficult to care for every student.

“We do realize that this year is going to be a heavy mental health support year,” said Liz Doncaster, Somerville’s director of student services. “These students basically have been out of school for two years, so they've missed two years of not only academics, but two years of social-emotional growth.”

In preparation for this year, administrators in Somerville hired six new social workers and staff members — four of whom are bilingual — to support the new students across the district. They plan to hire one more.

“We have lots of Spanish bilingual staff and some very talented Portuguese Brazilian multilingual staff, but not to the capacity to meet the need,” said Sarah Davila, the director of multilingual learner education for Somerville.

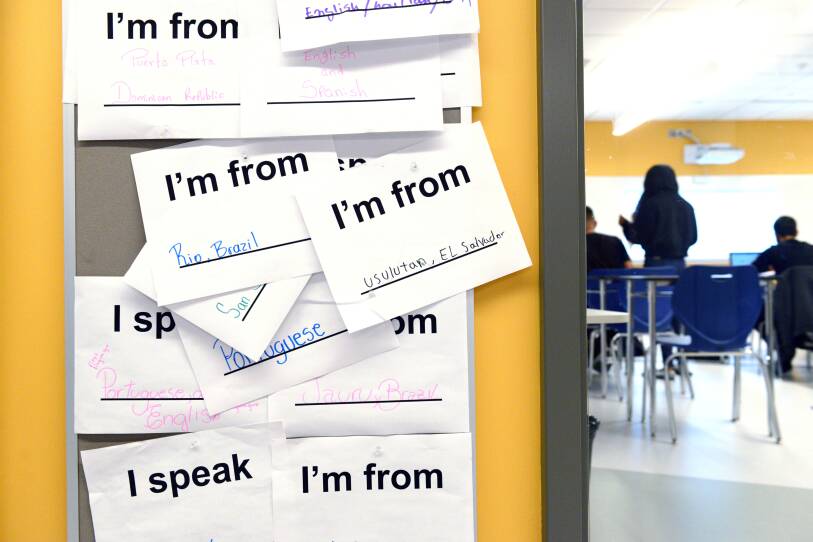

More than half of the new students this year are Portuguese speakers from families who emigrated from Brazil, and about a quarter are unaccompanied minors from other South American countries. About half of Somerville’s entire student population comes from immigrant households where their first language is not English.

The class of 161 new immigrant students marks a large increase from the past two school years. From July to September 2019, the district welcomed 69 students new to the United States. During those same months in 2020, there was just one.

In March 2020, Jennifer Ochoa was five months into her job as a family and community liaison at the East Somerville Community School. She described the situation as “chaos” after schools closed.

“Our families really heavily rely on school, not only for education, but they see it as a form of care for their children,” Ochoa said.

Schools are often where mental health professionals can reach immigrant communities who may otherwise not have the resources to find help on their own, according to Jeffrey Winer, an attending psychologist at Boston Children’s Hospital and instructor of psychology at Harvard Medical School.

“[Schools are] a common hub, and often for refugee and immigrant work, it's a really important place to anchor for delivery of services as opposed to in a clinic setting, because schools are — it's a more trusted [space],” he said.

Many Somerville families seek out Ochoa for help because she is bilingual. But when she needs to refer them out of the school system for services, such as outside psychologists, she says she can’t guarantee that they will be able to find support in their primary language.

“It’s, I think, very different for a kid to be with an interpreter versus a native speaker of their language, or fluent speaker, getting therapy in that language,” said Dot Kelleher, a psychologist and the director of family therapy training at Cambridge Health Alliance.

But, she explained, it’s hard to fill those roles. Kelleher has noticed that when a multilingual clinician starts accepting patients, their schedule fills up quickly because of the high demand.

Experts say immigrant families were disproportionately affected by the pandemic: they are more likely to have members who are essential workers, to live in multigenerational homes, to experience job loss and food insecurity and to lack digital tools to access online school.

Even as the pandemic wanes, many of those stresses haven’t, psychologists say.

“There are multiple layers of stress,” said Usha Tummala-Narra, a professor of counseling, developmental and educational psychology at Boston College. She is also a licensed psychologist who works with immigrant adults and adolescents.

“Some of these issues are not unique to the pandemic,” she added. “And in fact, over the last five years, it's the explicit rise in racism and xenophobia [that] has been playing an enormous role and has had a huge emotional toll on children and families.”

Psychologists say stigma around seeking mental health support in some — but not all — immigrant communities adds another barrier to accessing care. And among those wary people do seek help, they might wait until they are at a crisis point.

“Immigrants, I think, have a unique challenge when it comes to accessing health services, or putting it bluntly, knowing how to ask for help,” said Dr. Malak Rafla, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at Cambridge Health Alliance.

“I think they think twice, three times, many times before they do that,” he said. “There is always a ‘culture of caution,’ maybe even mistrust of the system or various establishments.”

Complicating the matter further: Even before the pandemic, the U.S. was facing a shortage of mental health support staff in schools. The number of school social workers can vary widely from district to district, with many not reaching the recommended ratio one for every 250 students.

Somerville now has 39 social workers for its almost 5,000 students, making its ratio approximately one counselor for every 126 students.

Psychologists say it is common to see an uptick in referrals for mental health needs around October and November, after the excitement of being back in school wears off.

Gloria Acosta, a clinical social worker at Cambridge Health Alliance who provides support in the teen health center at Somerville High School, says it’s been a “very welcome change” to be able to do therapy in-person this fall.

But, among the teenagers at her school, she has seen an increase in social anxiety, fear around the delta variant and a sense of loss and mourning for the high school experience they expected but never had.

“I do think that at some point I will likely be overwhelmed with the amount of referrals,” Acosta added. “I think as the reality sets in about the demands, the academics, social demands, that there's going to be an increase in anxiety and other problems.”

“Compared with pre-COVID era, I think we can see high levels for anxiety, stress and depression this year,” said Nancy Macias-Smith, a clinical psychologist who is the bilingual adjustment counselor at Somerville High School. “And that of course, affects the ability for the kids to focus, to be attentive and to concentrate.”

The staff in Somerville say they are prepared for an unusual school year. And Macias-Smith said she has been impressed by the resilience of the immigrant students and families she’s seen so far this fall.

“They are strong, resilient, intelligent and very eager to learn,” Macias-Smith said. “And we just want to take that pride in [helping] them to develop their social-emotional needs.”