Cedric Turner was 16 years old when bell bottoms were polyester and “The Bump” filled radio airwaves, moving young people to knock their hips together to the beat. It was the dawn of the disco era, with colored lights flashing in nightclubs as music blasted away.

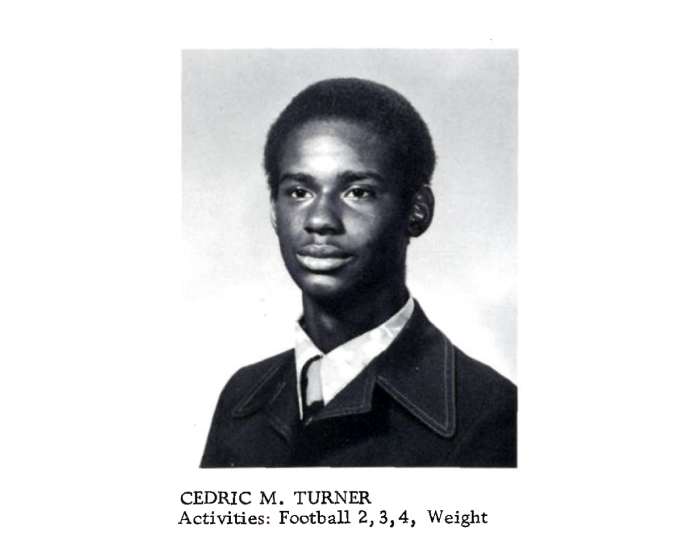

A street-wise kid from Mattapan, Turner was Black, six-foot-two and a standout football player at English High School in the Fenway. Until 1972, English was all boys, with some of the biggest, fastest athletes in the city.

But when Turner remembered the football games recently, his stories weren’t about high school glory days. They were stories of violent racist encounters.

The first year of desegregation, the team’s bus ride into East Boston for a game was harrowing. Angry white people came out of their homes to hurl rocks, bottles and the n-word at the mostly Black players as they arrived.

“We got these parents stoning us and calling us names, throwing sticks and rocks — grandmas, grandpas, mothers and fathers,” Turner said, recalling how the coach told them to duck down in their seats. “They was breaking the windows. And we’re like, what the hell. And then we have to play a game?”

Boston gets its racist reputation in part from the violent, televised reaction to court-ordered school desegregation of the 1970s. That violence was sprawling, and not limited to just South Boston and Charlestown. The thousands of traumatized Black children across the city who experienced it are the parents and grandparents of today’s students.

Key figures from that era say the next mayor of Boston must address the pain, rebuild trust and fix an educational system that, according to Harvard and the Boston Foundation, is once again intensely segregated.

“The problems that were manifest then are still in play. There’s no doubt about it,” said Marcy Murninghan, who was hired as a Harvard graduate student to help implement the desegregation order. “And that is the challenge of our time. The remedy may be very different and should be different. But the problem is still there.”

Turner, now 64 and a grandfather, speaks about his desegregation experiences rarely or only when asked. The subject can still make his eyes wet with tears. He considers himself a survivor of those damaging years thanks in part to the guidance of the city’s first Black principal, Robert Peterkin.

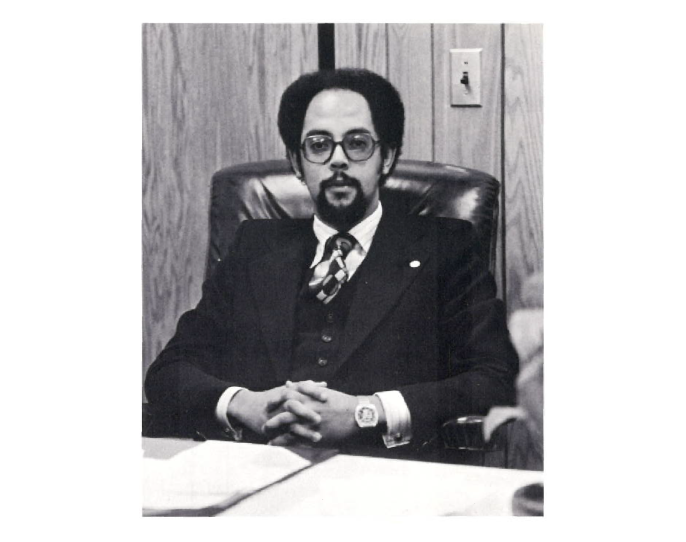

Peterkin became headmaster of English in 1974. No one told him about the desegregation court order when he arrived from Albany, N.Y., but he learned quickly. Just a few weeks after he started, as more white students enrolled at English for the first time, a riot broke out.

The cause wasn’t clear, but former teacher Joe Dotoli describes the incident in his book, A Piece of Chalk. “These were not the scuffles we were used to seeing,” the passage reads. “These were scary serious brawls. Kids were bleeding and running everywhere. ... Just as things were clearly spiraling out of control, we heard a noise that didn’t fit. Amid the yelling and cursing came a rhythmical stomping. It was the most eerie sight I have ever seen.”

The city had deployed a unit in riot gear with dogs and clubs to restore order. Peterkin, a reserved leader who favored three-piece suits, tried to stop the police onslaught, getting night-sticked in the process.

“I first met Cedric on Oct. 8, 1974, the day of the riot at English High School,” he said recently. “He was getting ready to punch a cop.”

The retired Harvard professor said he grabbed Turner by the collar and pushed him out of the way.

“I said, 'You’re not you’re not gonna do that.’ I said, 'You know, we’ve got the Boston Police, the FBI, the marshal’s office and we’re not going to do that,'” Peterkin recalled.

Turner says today that Peterkin’s intervention likely saved him from a lengthy prison sentence. That day 38 people were injured, and 7 were arrested.

The violence continued across the city with arrests, injuries and stabbings among students and protesters. The National Guard was mobilized.

Turner said just weeks later, a football game against South Boston High School at a neutral field in Hyde Park turned into an armed standoff.

“We’re out there practicing on the field the Southie bus pulls up — two of them — and then about 10 or 15 cars pull up behind them,” Turner recalled. “And then the cats get out the cars. And they had guns.”

He imitated the sound of weapons being cocked. Phone calls were made, and Black supporters of English arrived in response, also armed.

“And they was ready, they was ready,” he said, tears welling up. “And I’m like, it’s supposed to be a football game. So I’m sorry. I’m starting to get ... that brings back a lot of ... ”

Pain, he meant.

The game was brutal, with English losing 38–0. Peterkin had to be escorted from the stands by a phalanx of adults who feared for his safety. As the team’s bus rolled away, the rocks came again, fast and hard.

These are hard memories, but Turner had bigger problems to confront upon graduation. Raised by his mother in public housing, Franklin Field in Dorchester, he and his three siblings had little to no money. He won athletic and academic scholarships to attend Miami University in Ohio.

When scholarships didn’t cover the full cost of college, Peterkin deposited money in Turner’s bank account. He and a teacher paid Turner’s airfare to Ohio. Although he still “bled Blue” for English, Boston wasn’t his city. He still couldn’t walk through some parts of the city safely, and a stroll through South Boston was “a death sentence,” he said.

“I didn’t want to come back up here ever,” he said.

But trauma can inspire someone to move forward, too.

Turner went on to earn a degree in economics from Miami University. A program there also helped him overcome a severe speech impediment that had worsened in high school. His speech therapists in Ohio advised him to never return to Boston out of fear he might risk a relapse.

But he did return. He simply needed a job and his support network was in the city. His new employer? The Boston Public Schools.

Looking back, Turner views his experiences through a lens of race and class, calling desegregation a “rigged-up game.”

“They were sending Black kids who was supposedly in bad schools over to white schools that was equally as bad,” he said. “And white kids from a messed-up white school to a Black school that was equally as bad.”

Barbara Fields, the former head of the district’s Office of Equity during desegregation, said the violent racism that erupted in Boston often obscures another central fact: The federal court order also opened up opportunities for some Black students at better white schools.

“It was not about you have to sit beside a white students in order for you to learn, it was about the district providing resources — [the district] took better care of schools that were in white communities, schools that have a white student population,” she said.

But has Boston changed? Advocates say educational resources still are not spread fairly along race and power lines in the metro area. Black and brown students are concentrated in Boston and Gateway cities, while many suburbs with overwhelmingly white and Asian populations are known for their quality schools.

“We still have schools that are subpar for Black children. It’s just so disappointing,” said Kim Parker, president of the Black Educators Alliance of Massachusetts. “What we are asking for — for Black children and other children in the district — should not be like such a hard ask, right? We should not have to beg for clubs or activities that everyone in the suburbs has.”

Turner also said educators and the city’s leaders know what works, it’s a matter of mustering the political will to ensure that Black children succeed.

Despite the racial turmoil of the time, Turner said he got a pretty good education at English High. The school was in a brand-new building. He credits Peterkin with restoring order and offering extracurricular activities during the chaos of desegregation. It was no small task.

It was Peterkin who told Turner about the job in the Boston school system. He later took a position at John Hancock Investments and worked in the private sector. He settled into a comfortable life in Brockton just outside Boston, marrying Petri Morgan and starting a family.

Morgan happens to be the daughter of Tallulah Morgan, the lead plaintiff in the NAACP’s desegregation lawsuit. Her children, including Petri, were also named plaintiffs.

What Turner says he believes strongly, nearly 50 years after desegregation, is that Black kids need more resources to compete, not fewer. An economy that is driven by artificial intelligence, engineering and all things STEM demands it.

He founded Empower Yourself, a Brockton nonprofit that works with low-income Black students in middle and high schools to get them interested in science and math careers. His students enter academic competitions in economics, math and robotics. Sponsors include Fidelity, iRobot and MIT’s Lincoln Labs.

“I feel my job is leveling off the playing field for them,” Turner said.

He will call colleges, connect the students with internships and buy them plane tickets to competitions. Teachers refer some seventh-graders who don’t even know the meaning of STEM, the acronym for science, techology, engineering and math.

Turner’s own love of math came from his middle school teachers, who drilled him for two hours daily. They were white teachers at his all-Black middle school in Dorchester, the now-closed Frank V. Thompson. And those teachers were committed to one thing: education.

Correction: This article has been corrected to reflect that iRobot is a sponsor of the Brockton nonprofit Empower Yourself and Microsoft is not.