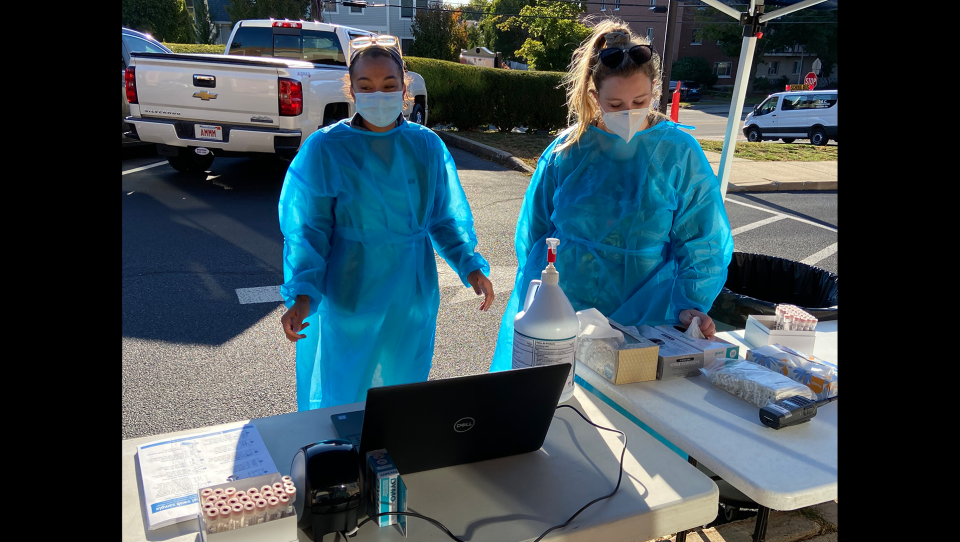

Watertown Public Schools tests hundreds of teachers for the coronavirus weekly, asking them to swab their own nostrils at a COVID-19 drive-through. The program, which began two weeks ago, didn’t require any persuading to get teachers on board.

“People want this,” said Superintendent Deanne Galdston. “It's not like, ‘Oh, you know, I'll do it if I feel like it.' It was like, 'No, no, no, I really want to do this.'"

Watertown is just one of several school districts in Massachusetts that has taken testing into its own hands. Neither the state Department of Elementary and Secondary Education nor the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend universal testing for public school students or teachers, calling it an unproven strategy. But a vocal group of school leaders and parent scientists say if testing is the rule at many colleges, businesses and even some private schools, why wouldn't public schools consider it?

Six Boston-area districts have teamed up with a group of volunteer scientists as part of what is called the Safer Teachers, Safer Students: Back-to-School SARS-CoV-2 Testing Collaborative Pilot. The goal is to help public schools determine what kind of testing they may need and help them get it.

Wellesley parent Jesse Boehm, a founding member of the group, is a cancer scientist at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. He said the Cambridge health research facility routinely processes millions of COVID-19 tests, including ones for more than 150 colleges. He was also part of a group that helped Wellesley school officials arrange testing more than 5,000 residents before schools opened this fall.

Boehm said it became clear that other communities wanted testing guidance from the scientific community, too. Parent scientists were ready to volunteer.

“We believed that the conversation [about testing] really wasn’t being had in a serious way in the public school setting for a diversity of reasons, mostly just due to sheer complexity,” he said. “But we decided that we had to try.”

The collaborative's scientists are currently working with six pilot districts — Brookline, Chelsea, Revere, Somerville, Watertown and Wellesley. In each community, there are many detailed considerations around what kind of testing is best (nasal, spit stick, pool testing, symptomatic, asymptomatic, etc.) and how to pick a reliable vendor that will turn around results quickly and efficiently. Then there's the looming question hanging over it all: How much will it cost?

Boehm says if the effort is successful, it will demonstrate how to reduce fear and anxiety about returning to school and pave the way toward ensuring that in-person learning can continue as long as possible. He said the testing will also create a framework that can be used by any community in the state. Since the pilot's launch, he said, another 10 districts have expressed interest in joining.

He said he hopes the findings will also help change the way decisions are made about when schools should remain open or move to remote or hybrid learning. Current state guidance instructs schools to base their decision to open or close on the community’s overall rate of infection per 100,000 residents. A district in the red, for example, has more than eight coronavirus cases per 100,000 residents and is supposed to only offer remote learning.

“We believe that decision-making on the transition states between remote, hybrid and full time in person should be driven by data on the number of cases in school,” members of the collaborative wrote in an Oct. 2 letter to Massachusetts Health and Human Services Secretary Marylou Sudders.

Overall in Massachusetts, 259 students and staff who attended school in-person tested positive for the virus between Sept. 24 and Oct. 7, according to the state's tally, even though most districts have yet to return full-time to classrooms.

Proponents of testing for students or teachers without symptoms say it can help identify virus carriers so they can be isolated before they have the chance to infect others. Such testing is underway in some large districts, including in New York City, which recently increased its testing of students and teachers to twice a week in COVID-19 hot spots. Boehm says as testing prices fall, more districts could consider it as a precaution until a vaccine arrives.

Yet testing is not a panacea. Epidemiologists have said communities need to be careful not to fall into thinking that testing alone will ensure their safety from the virus, noting that such thinking contributed to the outbreak at the White House. Mask-wearing, hand-washing and social distancing are advised as the best way to keeping infection at bay.

But in Revere, where positivity rates are high and schools are closed for in-person learning, testing can offer some hope.

The state already operates community-wide testing sites at some schools there. Superintendent Dianne Kelly said if there is a way the district can offer routine student testing, that would be transformative.

“It might enable a district like Revere, that could be red for a very long time, to actually have some in-person learning, even while we are in the red zone,” Kelly said.

Watertown funded its testing program with federal dollars for coronavirus relief. In Revere and other districts, the next challenge is finding a way to pay for one.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the number of COVID-19 tests processed by the Broad Institute.