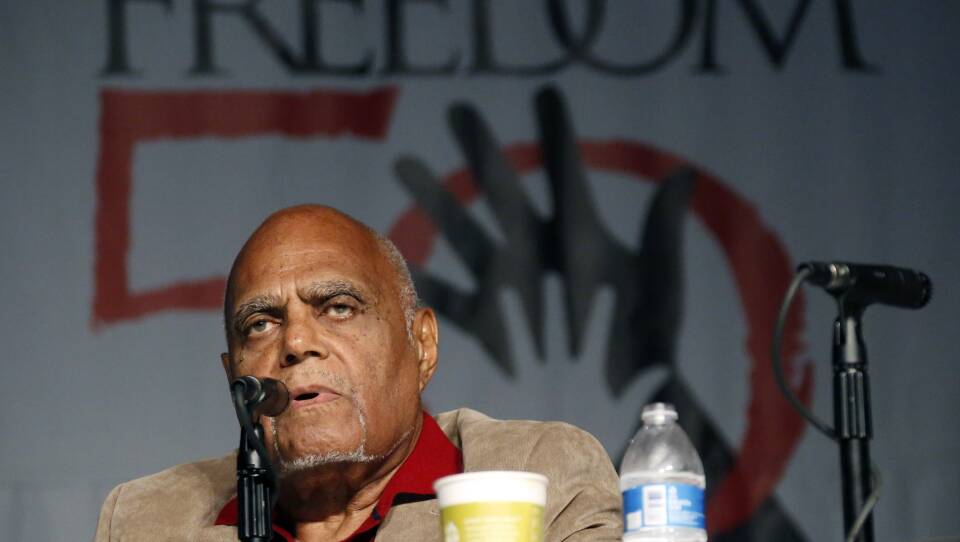

Robert “Bob” Moses died on July 25 of this year, but the history of Bob in the Cambridge public school system came freshly to mind because of a celebration of his life, organized by family and friends recently at the St. Mary Annunciation Church in Cambridge’s Central Square.

The death of Bob Moses was noted in prominently placed obituaries in just about every newspaper worth its salt: The Boston Globe, The New York Times and The Washington Post , as well as on GBH News and National Public Radio . All these obituaries reported one of his singular contributions, among many others: his founding of The Algebra Project in 1982. I reacted with nostalgia as I read these. They renewed my admiration for Bob, in large part because my son, Isaac Dorfman Silverglate, now in his mid-forties and living in Manhattan with his wife and two kids, benefitted hugely from Moses’ Algebra Project.

It’s a complicated story, not told in any of the obituaries, so I want to tell it here as my personal tribute to Bob’s genius.

Isaac attended the Martin Luther King, Jr. Elementary School in Cambridge, just a three-block walk from where my wife, Elsa Dorfman, and I lived in our house on Franklin Street. (I now occupy the Franklin Street house myself since Elsa passed away in May of last year.) It was either coincidence or fate that brought Bob Moses and Isaac — and Elsa and me — together. Isaac was in the class in which Moses got permission from the Cambridge school authorities to teach a math class that became known as the Algebra Project curriculum.

The Cambridge teachers' union tried to block Bob — a Harvard Ph.D. and already a legend in the national civil rights movement — from teaching algebra to fifth graders in a Cambridge public school, a story that I told in a GBH News column in 2014.

The Cambridge School Committee balked at the idea of Bob Moses teaching his innovative math curriculum in the King School for two reasons.

First, the Board was skeptical that algebra could be taught to children so young, but Bob insisted that he could indeed do so with his innovative program. Bob believed that algebra was the “gateway” skill that, once mastered, would enable young children to go on to master all forms of higher mathematics — trigonometry, calculus and physics. Bob further argued that enabling young kids to master such skills would give them confidence to master any academic subjects and skills.

Second, the Cambridge teachers’ union resisted Bob’s offer because he did not possess a teacher’s degree and teaching certificate. The parents attending that School Committee meeting (including Elsa and me) pushed back. Elsa’s and my attendance was a particular irritant to the union. We expressed curiosity how it came to be that the contract negotiations between the union and the school committee would be so hostile to the education of the supposed beneficiaries of the educational enterprise, namely the children.

I therefore attended a public session of the contract negotiations. At the time, any Cambridge taxpayer could attend the contract negotiations, with a signed letter from two members of the School Committee. I got those letters, showed up and the union’s negotiation team promptly left the negotiating table.

In the end, a compromise was reached: Bob would teach his experimental math course very early in the morning. The union assumed that very few kids would show up. Yet these early morning classes were packed. Even some parents showed up, curious how a man already reputed to be a genius would teach their young kids math. (When one uses the term “genius” to describe Bob Moses, the description should be taken literally. Moses was the recipient of a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant that enabled him to develop the Algebra Project.)

While the Cambridge School Committee, under pressure from the teachers’ union, was against Moses, the teachers at the King School were strongly in favor, and this, in addition to pressure from parents, doubtless gave Moses the additional support that he needed. One teacher in particular, whose name was Mary Lou Mehrling, welcomed Moses’ teaching algebra to her seventh and eighth grade students, and teachers at King Open School joined Mehrling in that support.

Bob Moses’ experiment in the King School was an overwhelming success. The vast majority of the students in that class went on to college, including a large cohort of Black and Hispanic kids who, statistically in those days, might not have had that chance.

The most interesting (to me, at least) aspect of the Algebra Project, which was not mentioned in any of the obituaries, was Bob’s method for getting fifth graders to understand negative numbers. Negative numbers are, after all, at the heart of mastering algebra. It can be difficult to get fifth graders to envision, much less master, negative numbers. After all, we could count on one hand the number one by raising one’s thumb; the index finger adds one more, equaling two. And so forth until five.

Here’s what Bob did: Bob took the class on a trip on the MBTA’s Red Line, which at the time stopped at the Harvard Square stop. He designated Park Street as “zero.” When the train reached Charles, that was plus one. The next stop (Kendall/MIT) was plus two. Then came Central (plus three), and finally Harvard Square (plus four).

Going in the other direction, starting again from Park: Downtown Crossing was minus one, South Station was minus two, Broadway was minus three and so forth. And lo and behold, every student in the class suddenly could envision negative numbers and, with that, master algebra. I was flabbergasted at how it took a genius like Bob Moses to come up with such a seemingly simple, but actually ingenious, method for teaching kids negative numbers, opening up the gateway for mastering higher mathematics. No wonder that the vast majority of the kids in that class went on to college.

I want to add just one more detail, and this is about Bob Moses as a person. Everything he did, at least that I could observe, he did with immense dignity and grace. I never saw him with a frown on his face. I never heard him utter an impatient or impolite sentence. He had the kind of personal bearing that was as respectful of adults as it was of children. Children and adults therefore reacted to him in much the same way. I think that this aspect of Bob Moses is ultimately what sticks in my mind as I imagine a world without him.

May he rest in peace.

Harvey Silverglate, a longtime GBH News contributor, is a criminal and civil liberties lawyer and writer who lives in Cambridge. He thanks his research assistant Emily Nayyer, as well as Elena “Lena” James, a now-retired teacher at the King School who was there when Dr. Moses taught his course, for assistance in the preparation of this piece.