I’m grieving as though I’ve lost someone in my family. I was watching CBS This Morning last week when Gayle King interrupted the show’s planned program with the breaking news that former Secretary of State Colin Powell, the first African American to serve in that role, had died. I never met him personally, but I regarded him with the respect accorded to elders in the family.

And he was a lauded member of the larger family of African American ‘firsts,’ those path breaking pioneers who overcame longstanding — sometimes near-impossible — obstacles. They achieved at the highest levels to enter circles previously closed to people of color.

I didn’t know who he was until President George H. W. Bush nominated him to be Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the first African American. I didn’t know that he had already broken through decades of closed doors when he served as assistant to the deputy secretary of defense under President Jimmy Carter before President Ronald Reagan named him his National Security Advisor — again the first African American. I didn’t know that, at 52 years old, he was the one of the youngest four-star generals, and that in nominating him, President Bush selected from a group of more than 30 other possible candidates. (A fact, according to reporting by the New York Times, that didn’t sit well with more than a few who felt they had been passed over for the prestigious assignment.) In his Rose Garden announcement, President Bush praised General Powell and emphasized, “It is most important that the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs be a person of “breadth, judgement, experience and total integrity.” Words many others would use to describe him throughout his career, and after his passing.

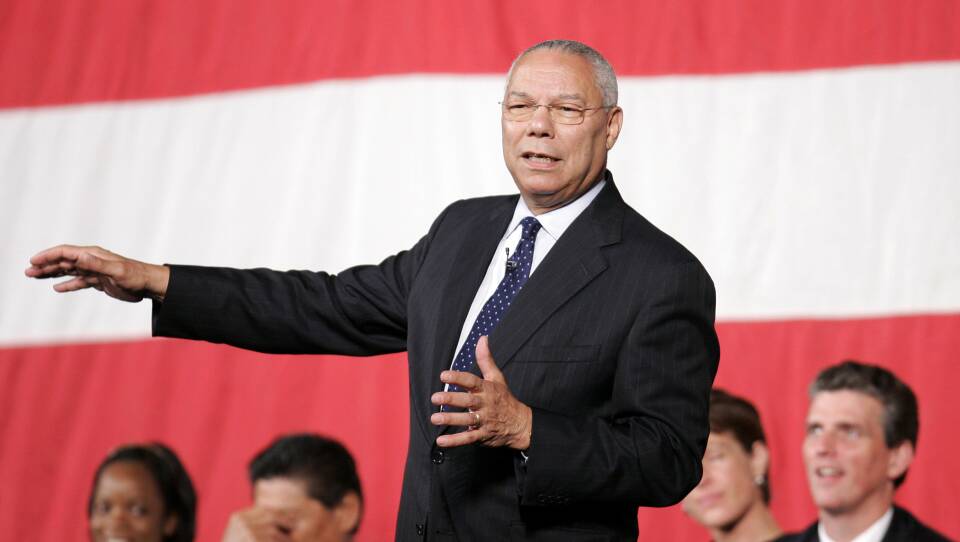

With the Joint Chiefs of Staff nomination, General Powell was propelled into a huge public spotlight and soon, like so many others, I was learning about his life story and career. Black people across the nation were proud, even as some were critical of his Republican party affiliation. General Powell made a few brief remarks in the Rose Garden pointing out the “stark opportunities and challenges” in leading the Joint Chiefs and saying how he was “especially privileged and somewhat humbled” to follow his predecessor into the role.

But, in the days following the official nomination, reporters had been unsuccessful in pinning him down for a substantive interview. So, it was a particular thrill for me and my fellow members of the National Association of Black Journalists when he agreed to speak first at our annual conference. His appearance was now a newsmakers’ event, drawing legions of our fellow reporters.

Though the pomp and circumstance was impressive, I was struck by his determination to use the platform to credit the Black folks who paved the way for him. On that day at the national conference, he was emotional as he talked about standing on the shoulders of the Buffalo Soldiers, the six all-Black units of men who protected the Western territories after the Civil War and the Tuskegee Airmen, the African American military pilots and airmen who fought in World War II. In a commencement speech a year later, he was even more emphatic, saying, “I will never forget my debt to them. I just didn’t show up; I climbed on the backs of those who never had the opportunity that I had.”

His words had a particular resonance for me and so many others in the room. We, too, were firsts in our newsrooms.

I am well aware that Secretary of State Colin Powell’s career was not without blemish, none bigger than his part in the weapons of mass destruction argument, which led to the Iraq war. And I have never shared his moderate don’t-rock-the-boat Republican politics. But I have nothing but admiration for how he used his “first” platform to make sure he was not the first and only, through quiet connections out of the public eye and through the youth-focused employment initiative, part of his America’s Promise Alliance.

Rest in peace, Secretary Powell. Yours was a life well lived and well served.