The buzzword of the 2020 Democratic Presidential nomination campaign, to date at least, is “electability.”

Journalists report, and polls support, the observation that Democratic primary voters are prioritizing victory in the general election as they size up the large and growing field of candidates.

What exactly that means, however, remains an open question.

“I do think it’s different from past cycles,” says Judy Reardon, long-time New Hampshire political activist and former advisor to U.S. Senator Jeanne Shaheen. Like most observers, she attributes that mainly to deep hostility for President Donald Trump: Democrats, still recovering from the shock of losing to him in 2016, are desperate to avoid a repeat in November 2020.

But, she adds, “Everybody probably has their own idea of what it will take to beat Donald Trump.”

Those differing definitions, unsurprisingly, seem to neatly overlap with what the individual wants in a Presidential nominee anyway.

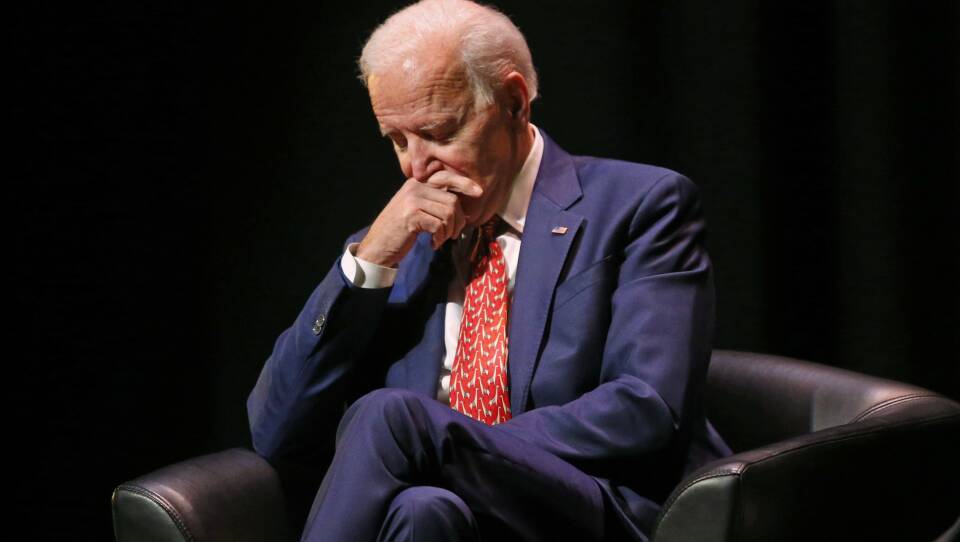

Joe Biden has reportedly been telling Democratic allies that he has the best chance to beat Trump, because of his rapport with many Rust Belt voters who swung the 2016 election (read: working-class white Catholics). Senator Sherrod Brown of Ohio and Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota point to their past success in that region as evidence that they’re most likely to win those states in 2020.

Bernie Sanders supporters have insisted that the socialist-leaning septuagenarian would have beaten Trump in 2016, and would do so again. Backers of Elizabeth Warren argue that the ideal candidate would offer Sanders’s liberal populism without the off-putting “socialist” label.

A college senior in New Hampshire, attending a Kamala Harris event this week, told the Union Leader that he is looking for “a bold progressive who is capable of running the energetic campaign necessary to beat Donald Trump.” Which happens to neatly describe the candidate he came to see.

That student is among the many arguing that only a pugilistic campaigner can square off with the current bully-in-chief—and energize turnout among the Democratic base. But another camp believes that will turn off the voters who will swing the general election, who, they believe, are desperate for an end to nasty partisan politics.

Among those making that argument, naturally, are supporters of former Governor John Hickenlooper of Colorado, and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who are both prepping likely campaigns stressing their ability to work pragmatically across the aisle.

And then there is a crop of younger, relatively centrist newcomers to national audiences—South Bend, Indiana, mayor Pete Buttigieg; former Texas congressman Beto O’Rourke; former Obama cabinet member Julián Castro; Montana Governor Steve Bullock; California congressman Eric Swallwell; Ohio congressman Tm Ryan; perhaps even Massachusetts congressman Seth Moulton—who eagerly point out that a half-century of history demonstrates that the only electable Democrats are younger, relatively centrist newcomers to national audiences: Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama.

They’re all perfectly decent theories, and all pretty much impossible to disprove this far out from the election. It’s easy enough to pick you pleasure, and then convince yourself that you’ve got the electable one. Or, thanks to the huge field of well-qualified pols, to start with your theory of electability and then find a candidate to match. Which comes first might be a chicken-and-egg question for political scientists to sort out after the fact.

Who Decides?

Part of what’s different this time around might be whose theories of electability matter.

Typically, at this stage of the election cycle, only a small percentage of Democrats are even paying attention to the candidates—and only a small percentage of them have any significant impact on the candidate “winnowing” process.

What usually matters at this stage are the small number of elite party players. That includes wealthy donors, influential interest-group leaders, elected officials, and others with outsized influence within the party.

Those elites have always tended to focus more on electability than average primary voters—mostly because they have very powerful interests in Democrats gaining power, whether in the form of jobs, contracts, issue agendas, or simply the personal power of having access to people in power.

But they also tend to have a more cautious, risk-averse notion of “electability” than many in the party base.

“We have to revisit the definition of electability,” says Arnie Arnesen, a Concord, New Hampshire talk-show host and Democratic activist. “And I don’t want it done by consultants and pollsters.”

Her wish might be coming true. Obviously it’s way too early to determine the relative influence of party elites versus rank-and-file activists in narrowing this 20-odd candidate field to the few who will remain viable when New Hampshire holds its primary a year from now, and who emerges from that group to win the nomination. But there’s some evidence that the balance is shifting.

As Bernie Sanders demonstrated in 2016, it has become increasingly possible for candidates to raise large sums—even Presidential-campaign sized sums—primarily through small-dollar online donations, from rank-and-file party members all over the country. Sanders claims to have raised nearly $6 million in just 24 hours after announcing his candidacy this week; that’s nearly as much, in one day, as John Edwards raised in the first three months on 2003, establishing himself as the top fundraiser and major contender for the 2004 nomination.

That’s one sign that the small percentage paying early attention has ballooned in this cycle. Campaign events are packed, for relatively obscure candidates as well as the famous names. At least anecdotally, that seems to be translating into campaign volunteerism, providing the much-needed “boots on the ground” that usually come at the direction of union leaders and other endorsing groups at this stage.

And modern communications might be giving candidates a platform for making their pitches, without the money and platform of those party elites.

This Wednesday afternoon, for example, NowThis posted a video—at the top of its Politics page, as an “Editor’s Pick”—of Buttigieg discussing his experience coming out as gay. It was NowThis that posted a video of O’Rourke answering a question about Colin Kaepernick last Fall, which went viral and propelled the Senate candidate to cult status among progressives all over the country. Prior to that point, O’Rourke was struggling with name recognition in his own state of Texas; today, he could enter the Presidential race as a national political and fundraising powerhouse.

It’s not that the party elites won’t matter; it’s just that every progressive voter with a Facebook and Instagram account will also matter. If the coming months bring a war, in part, over the meaning of “electability,” the battleground will be on those sites, as well as in the back rooms and country clubs.

Make A Stand, Not A Sacrifice

But again, will they really be debating electability, or just making an argument for the candidate they like?

It’s one thing to say that you’re prioritizing electability. The real test is whether Democrats are willing to sacrifice for it—to forego candidates with their preferred policies, positions, or characteristics, because of a belief that those very characteristics could prove costly in the general election.

Last year, I was surprised by how many Democratic activists—primarily women—confided to me that they had reluctantly concluded that their party needed to nominate a man in 2020. The experience of Hillary Clinton’s campaigns (against Obama in 2008, and against Sanders and Trump in 2016), among others, had convinced these Democrats that the country remains too resistant to women leaders.

For those individuals, turning their back on Elizabeth Warren and other potential women candidates represented a significant sacrifice.

Some have since changed their minds about that particular concern. The success of Democratic women in the 2018 midterm elections seemed to disprove the case.

Similarly, some enthusiasts of former Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick were convinced that it would be folly for the party to send a black candidate into the racial backlash that, they believe, helped Trump prevail after the Obama presidency. That concern also seems to have receded, though too late for Patrick.

As for ideology, there isn’t much evidence yet that Democrats are opting for candidates with more moderate positions, disproportionate to the ideological breakdown of the party. That might change as more of the candidates jump in, and become better known. For now, though, candidates seem to be singing from similar hymnals, with slight variations in tone.

One thing perhaps worth watching is how Democrats respond to Presidential candidates who, out of principle, limit their own fundraising and spending capacity.

That seems like a ready-made test of that professed willingness to sacrifice principle for electability. If electability is king, the party should reject any candidates who would put themselves at competitive disadvantage.

So far, all the declared Democratic candidates have pledged to reject contributions from corporate PACs. But, only a few—Warren, Harris, and New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand—extend that ban to federal lobbyists. None so far are rejecting Wall Street contributors or big-money bundlers. And while Warren has criticized Super PACs, she has not suggested a Presidential version of the “People’s Pledge” that kept outside groups from spending in her 2012 U.S. Senate campaign against Scott Brown.

There has been some backlash to all this, mostly in the form of party elites complaining in the press about the folly of any form of unilateral financial disarmament.

But, will the party actually come to see, and punish, clean-hands campaigns as forms of electability flaws? Let the eye of the beholder decide.