You might be wondering whether to read this. After all, what can be said about the Harvey Weinstein story that hasn’t already been said?

Plenty, actually.

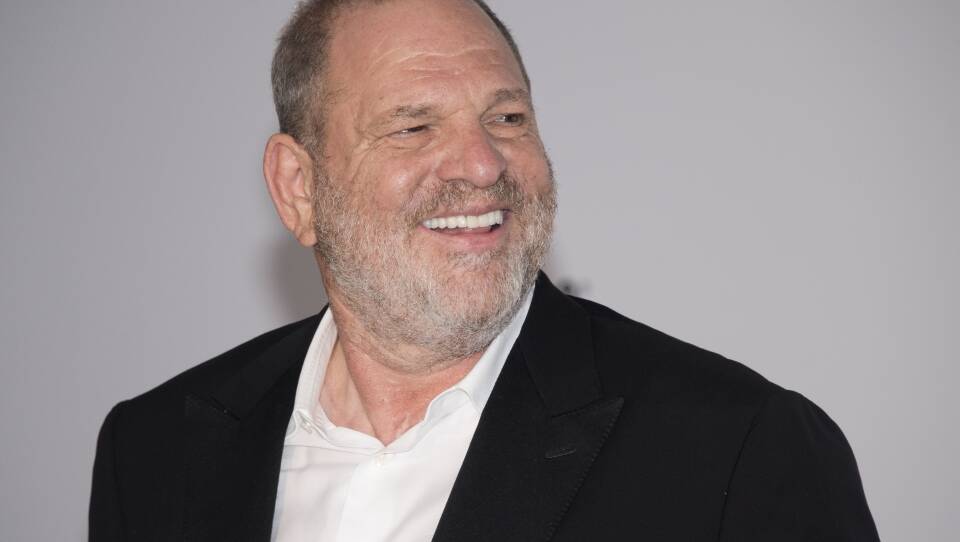

Quick background for those who’ve somehow missed the news: in a New York Times investigative piece published Oct. 5, and in a New Yorker piece published five days later, Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein has been accused of sexual harassing, assaulting, and raping multiple women over several decades.

The online version of the New Yorker story embeds chilling audiotape of Weinstein admitting to groping the actress Ambra Battilana Guitierrez as he intensely pressures her to enter his hotel room. The audiotape was recorded in 2015 by the special victims division of New York police who were investigating Guitierrez’s complaint that Weinstein had sexually assaulted her during a business meeting.

The Weinstein story has launched a flotilla of commentary on the problem of sexual harassment and assault. Most pieces remark on the seeming shift in public consciousness that has opened the floodgates for on-the-record public complaints about powerful men like Bill O’Reilly, Roger Ailes, Bill Cosby, Donald Trump—and now Weinstein—who have abused women for years but are only just now being held accountable (with the notable and lamentable exception of Trump).

Despite the much-welcomed public attention now being paid to sexual violence, it is a sign of how much further we have to go that few (if any) of these pieces have made the following observations.

First, committing sexual assault has little to do with sex. The thrill for the offender is in exerting power and control over an intimate part of the victim’s humanity. And while the vast majority of adult victims are women, men get assaulted, too. In a tweetstorm demonstrating these points, Terry Crews, a six-foot-three-inch, 240-pound former football player turned actor who stars in Brooklyn Nine-Nine, revealed that he had been assaulted by a “high level Hollywood executive” (not Weinstein) who “groped” Crews at a Hollywood party.

Although Crews immediately told many people about what had happened, including those who worked with the man who had assaulted him, Crews opted not to file a complaint. “I decided not 2 take it further becuz I didn’t want 2b ostracized— par 4 the course when the predator has power n influence,” Crews tweeted.

Second, the Weinstein and Fox News stories are not grotesque outliers (though the breadth and depth of Weinstein’s alleged assaults is staggering). This is happening in workplaces across America. As you read this, someone is being sexually harassed or assaulted by a coworker who is, more often than not, the boss. Worse, the victim is not a high-profile Hollywood actor or television news anchor who will be heard when the public is finally (as it seems to be now) ready to listen. That person is a nurse working the night shift; a retail employee serving up cups of morning coffee; a tech center operator fielding calls about smartphones; a young reporter learning the business at an edgy online outlet; a middle manager at an insurance company; a social worker at a human services agency. When they disclose the abuse, they risk retaliation, loss of employment, or both.

Last, it cannot be said often enough that questions about what a victim said, did, wore, and drank before, during, and after an assault are wholly irrelevant. Ending sexual harassment and assault will only happen when we find ways—be they behavioral or punitive or both—to prevent sexual harassment and assault from happening in the first place. Focusing on the words and deeds of the offenders will tell us all we need to know, and we have now heard on tape what is normally only heard by the victim, and it is terrifying. We need to get serious about preventing assault if we want out of this mess altogether.

The Weinstein story tells us that workplaces require sturdy guardrails for behavior. Explicit, written policies banning sexual harassment and assault as well as workplace bullying must be in place, and they must apply to everyone, including the boss. Workplace safety policies must clearly outline the steps for reporting abuse. A policy that fails to define punishment for transgressions is effectively useless. A policy that defines punishment but does not empower anyone to enforce it is also useless.

When the public learns about a case like Weinstein’s—where no such policies existed and nearly everyone surrounding Weinstein either knew of his behavior and said nothing about it; passively enabled it; or actively protected Weinstein by threatening victims—the public must be ruthless in demanding accountability. This can come in the form of prosecution for past crimes; demands for new laws allowing nondisclosure agreements to be broken when there is reason to believe they are covering up criminal behavior; and economic boycotts of products. We can also make a personal commitment to believe a coworker when they disclose sexual abuse, even when the offender is the most powerful person in the room.

The burden on individuals to expose predators like Weinstein is almost unimaginable. It takes immense courage to report sexual assault. The longer we rely on survivors alone to end it, the longer we will be living with the problem. We must create more pathways for reporting abuse and holding offenders accountable in ways that do not re-victimize survivors.

Gina Scaramella is the executive director of the Boston Area Rape Crisis Center.