In New England, the road oft taken is poetry. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Phillis Wheatley, Emily Dickinson, E.E. Cummings, Jack Kerouac, Sylvia Plath and Robert Frost are just a few of the innumerable poets from these parts. Cambridge alone is populated with a U.S. Poet Laureate and a Nobel Laureate .

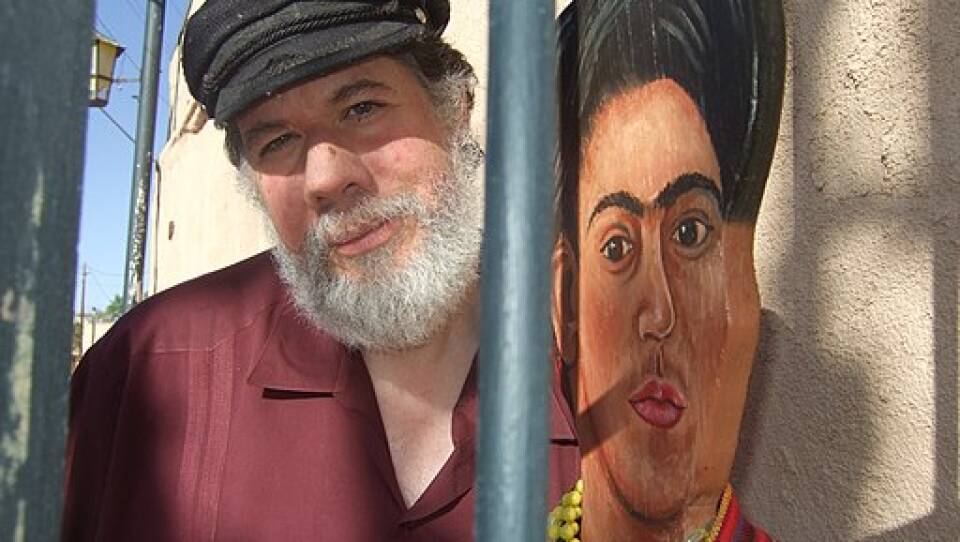

To celebrate this New England tradition, GBH is profiling local poets every Friday of National Poetry Month. Open Studio host Jared Bowen recently spoke with Martín Espada about his work.

Espada, a poet and professor at UMass Amherst, won the 2021 National Book Award for "Floaters," a poetry collection named for a piece he wrote in response to the photograph of Óscar Alberto Martínex Ramírez and his young daughter , two migrants whose bodies were found face down in the Rio Grande. He said that image sparked outrage and grief, but it also sparked "trutherism" and commentary as to whether the image was doctored or staged.

"Alongside the photograph, there was this commentary specifically in the ' I'm 10-15' Border Patrol Facebook group page , an anonymous commenter questioning this photograph — questioning whether this was doctored or staged," he said. "So I wrote the poem in response to that photograph, but also in response to that Facebook post and the mentality behind it."

Espada said poetry can capture intangible qualities and move people in ways that other media cannot. To fill out narrative details and put readers in a scene, he incorporates journalistic sourcing into some of his work. With "Floaters," he read everything he could, in both English and in Spanish.

"I'm also connected to an organization called Witness at the Border," he said. "So this group of border activists had not only information, but a certain sensibility that I wanted to tap into and that I wanted to share."

Espada previously worked as an attorney in Chelsea. He was a supervisor for a legal services program for low-income, Spanish-speaking tenants. Espada said advocacy is the common thread between his prior work and his poetry. Much of his work deals with human rights and social justice issues, including one poem based on his experience in Chelsea.

"There is a poem in this book called ' Jumping Off the Mystic Tobin Bridge ' that tells the tale of my time in Chelsea and one particularly vociferous argument with a taxi driver who had warned me when I got into his cab to be careful in Chelsea. Because, as he put it, 'There's a lot of Josés around here,'" Espada recalled. "I felt ethically bound to inform him that indeed, I'm a José and I'm Puerto Rican. And in fact, that I go to court and represent all the Josés there. So I was quite the nightmare for him, especially since we were stuck in rush-hour traffic on the bridge together."

The poet said those two two words — "the Josés" — were both racist and inventive.

"There are plenty of other words he could have used — words that have been used on me," he said. "Certainly, he didn't use them. He came up with something on his own. ... It stands in for a whole series of prejudices, a whole series of acts of discrimination taking place not only in Chelsea in the past, but in this entire country."

Espada hopes that his poetry will contribute as a form of historical record.

"I wonder, sometimes, assuming this poetry survives, assuming anything of this culture survives, is this the way people will understand what we went through? Does this contribute in some way?" he said. "I hope it does. There's no way to prove that, of course. We just have to keep writing."