Some describe America in the spring of 1968 as a country hell bent on tearing itself apart over two issues: the Vietnam War and civil rights. Martin Luther King Jr. had led the civil rights movement with peaceful methods. Yet his assassination on April 4 led to violence in almost 130 cities.

Although there were sporadic incidents of violence in Boston, it likely would have been worse, had it not been for a landmark concert at the old Boston Garden, broadcast on WGBH TV and radio the night after King’s death. But it almost didn't happen. I was a graduate student working at WGBH at the time, and I watched the broadcast in the TV studio control room on Western Avenue in Allston.

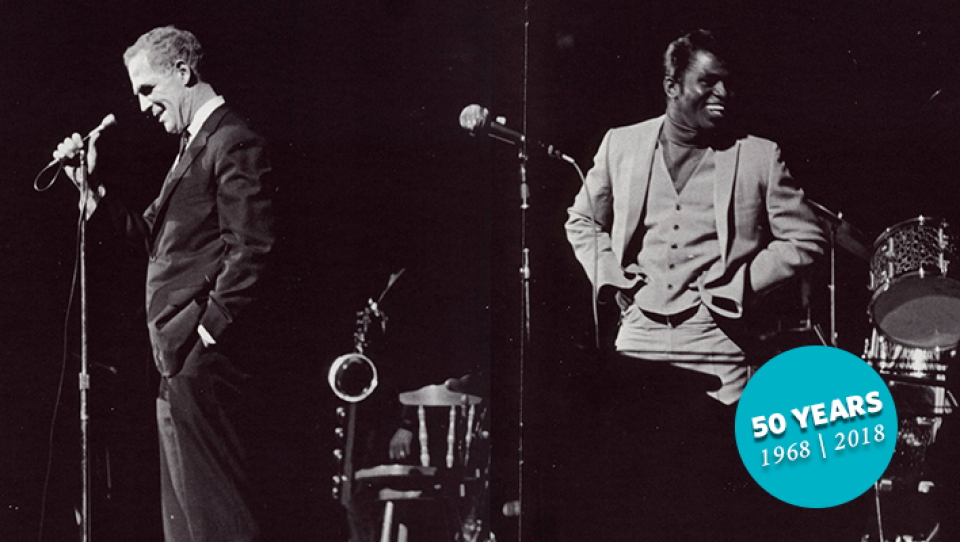

Amid the grief the nation was experiencing the day after King’s assassination, word began circulating in the building about a plan for WGBH to broadcast a previously scheduled concert at Boston Garden. It starred the “Godfather of Soul,” James Brown, the most popular, charismatic and powerful black entertainer of the day.

At first Kevin White, who had been Boston’s mayor for barely three months, wanted to cancel the concert, fearing it could provoke the kind of rioting that so many American cities had seen after King’s death. White had no idea who Brown was, thinking he was instead the former professional football star Jim Brown, according to James Sullivan, author of “The Hardest Working Man: How James Brown Saved the Soul of America.”

It was up to gospel and soul music deejay Jimmy Byrd, along with Tom Atkins, the lone African-American on the Boston City Council, to convince White that not having the concert could be more dangerous than letting it happen. In his book, Sullivan says that Atkins told the mayor: "You can't cancel the James Brown show because if you do that, you're going to have 14,000 kids showing up at the Boston Garden finding out by a piece of paper stuck on the door that the show has been canceled and, if they're not already angry and distraught over the murder of Dr. King, now they're really going to be mad."

White reluctantly agreed to let the show go on.

Then someone on White’s staff suggested that WGBH broadcast the concert live, so people could watch the show at home and not have to go out. Sullivan told me how Brown reacted when he heard the concert was to be televised: "'Well, if you put the show on TV for free, who's going to come?' So, he said, 'I'll do it if the city government can promise me some money.'”

When White learned of Brown’s demand, he almost cancelled the concert a second time. Once again, Atkins persuaded White that the cost to the city in terms of public safety and his own reputation would be far greater than the $60,000 Brown wanted.

Meanwhile, the executives at WGBH were debating the wisdom of such a broadcast. On the one hand, it would great public service; on the other hand, they could end up airing a riot. The associate director of programs at the time, Michael Ambrosino, told me the final word giving the go-ahead didn’t come down until 5:30, just three hours before the show was to begin. Not waiting for a final decision, Ambrosino had already begun assembling “the one group of guys who could pull off such a last minute live broadcast: producer Russ Morash, director David Atwood, along with [crew] Al Potter and Greg Harney.”

They made their way down to the Garden in a large white tractor-trailer that was the station’s new mobile unit. Using three old black-and-white cameras, borrowed cables that WBZ used to broadcast sports from the arena, an improvised feed from the public address system and only a couple of spotlights for lighting, they were ready to go after a delay of just 45 minutes. Although Atwood told me he and the crew were aware that violence could break out, they didn’t have time to think about their own safety because they were so focused on doing what they had to do to get the concert on the air.

Instead of the 14,000 concertgoers who could have filled Boston Garden at the sold-out show, only about 2,000 adoring fans showed up. They cheered loudly as Brown came on stage. He took the opportunity to heap praise upon Atkins for “being a black man in the driver’s seat” and White as a “swingin’ cat” for allowing the concert to take place and having the city pay for it. Although it was never revealed just how much Brown was paid, it was rumored he never got all the money he wanted.

As the three-hour concert got underway, I remember watching in the control room and seeing the videotape machines running. They were recording the show so it could be rebroadcast all night and doing that, many believe, was the key to keeping the city quiet.

At one point, some of Brown’s young fans tried to climb up onto the stage just to be near him. Boston police officers moved in quickly, some with billy clubs, ready to subdue the crowd. Brown dramatically took control, keeping the police at bay and convincing the crowd their behavior was making him and all black people look bad. They eventually took their seats, and Brown resumed the show. It was a tense moment that demonstrated the power Brown had over his audience and his ability to prevent what might have been a violent scene.

Back in the control room, we were mesmerized by Brown’s performance and amazed that the broadcast was going so well. But we were also anxious about what might be happening on the streets of the city. At 11 p.m. we watched newscasts on other local TV stations to see if any violence had erupted, but to our great relief, all was peaceful. As WGBH jazz deejay Al Davis, who attended the concert as a teenager, later recalled, “The ride home on the T was so quiet it was surreal.”

Some say there is no proof that Brown's concert kept Boston from boiling over. State Representative Byron Rushing told me Roxbury residents had been so traumatized by rioting in August 1967 that left some Blue Hill Avenue businesses destroyed that they did not want a repeat of that kind of violence.

But Sullivan told me: "Historians have looked at the James Brown concert as one of the major events in Boston that night that kept people home, kept them off the streets and kept the peace, whereas many, if not most, of the other major cities around the country experienced a lot of rioting that night."

The concert marked a significant turning point in WGBH’s history as well. Until then, producer Morash told me, the station had been broadcasting primarily instructional shows like “The French Chef with Julia Child” geared to a white audience and rarely got involved in local issues.

With the James Brown broadcast, WGBH was thrown suddenly into the role of responding to one of the most turbulent events of the time. For many members of its board of trustees, it was exactly the kind of programming the station should be doing.

What took place that night influenced programs to come like "Say Brother," which became "Basic Black" and is still airing today. Another landmark live broadcast in 1968, coordinated by WGBH, involved several public TV stations nationwide and dealt with the agonizing controversy over the Vietnam War.